Tesofensine

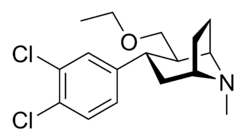

Tesofensine (NS2330) is a serotonin–noradrenaline–dopamine reuptake inhibitor from the phenyltropane family of drugs, which is being developed for the treatment of obesity.[1] Tesofensine was originally developed by a Danish biotechnology company, NeuroSearch, who transferred the rights to Saniona in 2014.[2]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 90% |

| Metabolism | 15–20% renal; hepatic: CYP3A4 |

| Elimination half-life | 220 hours |

| Excretion | Not applicable |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H23Cl2NO |

| Molar mass | 328.28 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

As of 2019, tesofensine has been discontinued for the treatment of Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease but is in phase III clinical trial for obesity.[3]

History

Tesofensine was originally investigated for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease,[4] and was subsequently dropped from development for these applications after early trial results showed limited efficacy for treatment of these diseases.[5][6] However, weight loss was consistently reported as an adverse event in the original studies, especially in overweight or obese patients.[7] Therefore, it was decided to pursue development of tesofensine for the treatment of obesity.

Tesofensine primarily acts as an appetite suppressant, but possibly also acts by increasing resting energy expenditure.[8] Phase II clinical trials for the treatment of obesity have been successfully completed.

Pharmacology

Metabolism and half-life

Tesofensine has a long half-life of about 9 days (220 h)[4] "and is mainly metabolized by cytochrome P4503A4 (CYP3A4) to its desalkyl metabolite M1" NS2360.[9][10] NS2360 is the only metabolite detectable in human plasma. It has a longer half-life than tesofensine, i.e. approximately 16 days (374 h) in humans, and has an exposure of 31–34% of the parent compound at steady state. In vivo data indicate that NS2360 is responsible for approximately 6% of the activity of tesofensine. As in animals, the kidney appears to play only a minor role in the clearance of tesofensine in humans (about 15–20%).

Transporter selectivity

Originally it had been reported that Tesofensine has IC50 of 8.0, 3.2 and 11.0nM at the DAT, NAT and 5HTT.[11] More recently, though, the following data was submitted: IC50 (nM) NE 1.7, SER 11, DA 65.[[12] cited in [13]] The revised IC50's would adequately explain the lack of efficacy in treating Parkinson's disease, i.e. insufficient DRI potency relative to the SERT and the NET. This could also help account for why Tesofensine is not reliably self-administered by human stimulant abusers[14] since it has been believed to be the case that DAT inhibition is necessary for this and not NET inhibition.[15][16]

Tesofensine also indirectly potentiates cholinergic neurotransmission[17] proven to have beneficial effects on cognition, particularly in learning and memory. Sustained treatment with tesofensine has been shown to increase BDNF levels in the brain, and may possibly have an antidepressant effect.[12]

Clinical trials

Phase IIB trial (TIPO-1) results reported in The Lancet[18] showed levels of weight loss over a 6-month period that were significantly greater than those achieved with any currently available drugs. Patients lost an average of 12.8 kg on the 1 mg dose, 11.3 kg on the 0.5 mg dose and 6.7 kg on the 0.25 mg dose, compared with a 2.2 kg loss in the placebo group.

All participants were instructed to follow a diet with a 300 kcal deficit and to increase their physical activity gradually to 30–60 minutes of exercise per day. The placebo-subtracted mean weight losses were 4.5%, 9.2% and 10.6% in the 0.25 mg, 0.5 mg and 1 mg dose groups, respectively. This is approximately twice the weight loss produced by medications currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of obesity.

NeuroSearch has also reported interim results[8] from a 48-week, open-label, extension trial (TIPO-4) in which 140 patients who completed the 24-week phase IIB trial (TIPO-1) were re-enrolled after an average of 3 months’ wash-out. All were initially treated with 0.5 mg tesofensine once daily but up-titration to 1.0 mg once daily was allowed in the first 24 weeks of the extension study. At this time point, all subjects were continued on the 0.5 mg dose for an additional 24 weeks. The 24-week interim results for those who were previously treated with tesofensine 0.5 mg in TIPO-1 showed a total mean weight loss of between 13 kg and 14 kg over 48 weeks of treatment. Furthermore, TIPO-4 confirmed the TIPO-1 results since those patients who were previously treated with placebo lost approximately 9 kg in the first 24 weeks of the TIPO-4 study.

Adverse events

In general, the safety profile of tesofensine is similar to currently approved medications for the treatment of obesity. The most commonly reported side effects in the obese population were dry mouth, headache, nausea, insomnia, diarrhea and constipation. A dose-dependent pattern was observed for dry mouth and insomnia. The overall withdrawal rate due to adverse events in clinical trials in the obese population was 13% with tesofensine and 6% with placebo. Blood pressure and heart rate increases with the therapeutically relevant doses of tesofensine (0.25 mg and 0.5 mg) were 1–3 mmHg and up to 8 bpm, respectively.[8][18]

At the conclusion of phase II clinical trials, Saniona announced that tesofensine was well tolerated with low incidence of adverse events, low increase in heart rate and no significant effect on blood pressure.[19]

See also

References

- Doggrell SA. "Tesofensine – a novel potent weight loss medicine. Evaluation of: Astrup A, Breum L, Jensen TJ, Kroustrup JP, Larsen TM. Effect of tesofensine on bodyweight loss, body composition, and quality of life in obese patients: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2009 372; 1906–13" Doggrell SA (July 2009). "Tesofensine--a novel potent weight loss medicine. Evaluation of: Astrup A, Breum L, Jensen TJ, Kroustrup JP, Larsen TM. Effect of tesofensine on bodyweight loss, body composition, and quality of life in obese patients: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2008;372:1906-13" (PDF). Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 18 (7): 1043–6. doi:10.1517/13543780902967632. PMID 19548858. S2CID 207475155.

- "NeuroSearch A/S signs agreement to transfer Phase I-II projects NS2359 and NS2330 (Tesofensine)". NeuroSearch company announcement. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- "Tesofensine - Saniona". AdisInsight. Springer Publishing. 29 January 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- Bara-Jimenez W, Dimitrova T, Sherzai A, Favit A, Mouradian MM, Chase TN (October 2004). "Effect of monoamine reuptake inhibitor NS 2330 in advanced Parkinson's disease". Movement Disorders. 19 (10): 1183–6. doi:10.1002/mds.20124. PMID 15390018. S2CID 21287239.

- Hauser RA, Salin L, Juhel N, Konyago VL (February 2007). "Randomized trial of the triple monoamine reuptake inhibitor NS 2330 (tesofensine) in early Parkinson's disease". Movement Disorders. 22 (3): 359–65. doi:10.1002/mds.21258. PMID 17149725. S2CID 37878251.

- Rascol O, Poewe W, Lees A, Aristin M, Salin L, Juhel N, et al. (May 2008). "Tesofensine (NS 2330), a monoamine reuptake inhibitor, in patients with advanced Parkinson disease and motor fluctuations: the ADVANS Study". Archives of Neurology. 65 (5): 577–83. doi:10.1001/archneur.65.5.577. PMID 18474731.

- Astrup A, Meier DH, Mikkelsen BO, Villumsen JS, Larsen TM (June 2008). "Weight loss produced by tesofensine in patients with Parkinson's or Alzheimer's disease". Obesity. 16 (6): 1363–9. doi:10.1038/oby.2008.56. PMID 18356831.

- NeuroSearch. "Tesofensine". http://www.neurosearch.dk/Default.aspx?ID=118 Accessed 17 May 2010.

- Lehr T, Staab A, Tillmann C, Trommeshauser D, Raschig A, Schaefer HG, Kloft C (July 2007). "Population pharmacokinetic modelling of NS2330 (tesofensine) and its major metabolite in patients with Alzheimer's disease". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 64 (1): 36–48. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02855.x. PMC 2000606. PMID 17324246.

- Lehr T, Staab A, Tillmann C, Nielsen EØ, Trommeshauser D, Schaefer HG, Kloft C (January 2008). "Contribution of the active metabolite M1 to the pharmacological activity of tesofensine in vivo: a pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modelling approach". British Journal of Pharmacology. 153 (1): 164–74. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707539. PMC 2199391. PMID 17982477.

- Jorgen Scheel-Kruger, Peter Moldt, Frank Watjen. Tropane-derivatives, their preparation and use. U.S. Patent 6,288,079

- Larsen MH, Rosenbrock H, Sams-Dodd F, Mikkelsen JD (January 2007). "Expression of brain derived neurotrophic factor, activity-regulated cytoskeleton protein mRNA, and enhancement of adult hippocampal neurogenesis in rats after sub-chronic and chronic treatment with the triple monoamine re-uptake inhibitor tesofensine". European Journal of Pharmacology. 555 (2–3): 115–21. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.10.029. PMID 17112503.

- Marks DM, Pae CU, Patkar AA (December 2008). "Triple reuptake inhibitors: the next generation of antidepressants". Current Neuropharmacology. 6 (4): 338–43. doi:10.2174/157015908787386078. PMC 2701280. PMID 19587855.

- Schoedel KA, Meier D, Chakraborty B, Manniche PM, Sellers EM (July 2010). "Subjective and objective effects of the novel triple reuptake inhibitor tesofensine in recreational stimulant users". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 88 (1): 69–78. doi:10.1038/clpt.2010.67. PMID 20520602. S2CID 39849071.

- Wee S, Wang Z, He R, Zhou J, Kozikowski AP, Woolverton WL (April 2006). "Role of the increased noradrenergic neurotransmission in drug self-administration". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 82 (2): 151–7. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.09.002. PMID 16213110.

- Wee S, Woolverton WL (September 2004). "Evaluation of the reinforcing effects of atomoxetine in monkeys: comparison to methylphenidate and desipramine". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 75 (3): 271–6. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.03.010. PMID 15283948.

- http://eprints.qut.edu.au/29667/1/c29667.pdf

- Astrup A, Madsbad S, Breum L, Jensen TJ, Kroustrup JP, Larsen TM (November 2008). "Effect of tesofensine on bodyweight loss, body composition, and quality of life in obese patients: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Lancet. 372 (9653): 1906–1913. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61525-1. PMID 18950853. S2CID 30725634.

- "Saniona's tesofensine meets primary and secondary endpoints in Phase 3 obesity registration trial" (Press release). Saniona AB. GlobeNewswire. 17 December 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2019.