Kava

Kava or kava kava (Piper methysticum: Latin 'pepper' and Latinized Greek 'intoxicating') is a crop of the Pacific Islands.[1] The name kava is from Tongan and Marquesan, meaning 'bitter';[1] other names for kava include ʻawa (Hawaiʻi),[2] ʻava (Samoa),[3] yaqona or yagona (Fiji),[4] sakau (Pohnpei),[5] seka (Kosrae),[6] and malok or malogu (parts of Vanuatu).[7] Kava is consumed for its sedating effects throughout the Pacific Ocean cultures of Polynesia, including Hawaii and Vanuatu, Melanesia, some parts of Micronesia, such as Pohnpei and Kosrae, and the Philippines.

| Kava | |

|---|---|

| |

| Piper methysticum leaves | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Magnoliids |

| Order: | Piperales |

| Family: | Piperaceae |

| Genus: | Piper |

| Species: | P. methysticum |

| Binomial name | |

| Piper methysticum | |

The root of the plant is used to produce a drink with sedative, anesthetic, and euphoriant properties. Its active ingredients are called kavalactones.[8] A systematic review done by the British nonprofit Cochrane concluded it was likely to be more effective than placebo at treating short-term anxiety.[9]

Moderate consumption of kava in its traditional form, i.e., as a water-based suspension of kava roots, has been deemed to present an "acceptably low level of health risk" by the World Health Organization.[10] However, consumption of kava extracts produced with organic solvents, or excessive amounts of poor-quality kava products, may be linked to an increased risk of adverse health outcomes, including potential liver injury.[10][11][12]

History and names

Kava is conspecific with Piper wichmannii, indicating Kava was domesticated from Piper wichmannii (syn. Piper subbullatum).[13][14] Kava originated in either New Guinea or Vanuatu by seafarers.

It was spread by the Austronesian Lapita culture after contact eastward into the rest of Polynesia. It is endemic to Oceania and is not found in other Austronesian groups. Kava reached Hawaii, but it is absent in New Zealand where it cannot grow.[14][15][16] Consumption of kava is also believed to be the reason why betel chewing, ubiquitous elsewhere, was lost for Austronesians in Oceania.[17]

According to Lynch (2002), the reconstructed Proto-Polynesian term for the plant, *kava, was derived from the Proto-Oceanic term *kawaR in the sense of a "bitter root" or "potent root [used as fish poison]". It may have been related to reconstructed *wakaR (in Proto-Oceanic and Proto-Malayo-Polynesian) via metathesis. It originally referred to Zingiber zerumbet, which was used to make a similar mildly psychoactive bitter drink in Austronesian rituals. Cognates for *kava include Pohnpeian sa-kau; Tongan, Niue, Rapa Nui, Tuamotuan, and Rarotongan kava; Samoan, Tahitian, and Marquesan ʻava; and Hawaiian ʻawa. In some languages, most notably Māori kawa, the cognates have come to mean "bitter", "sour", or "acrid" to the taste.[14][18][19][20]

In the Cook Islands, the reduplicated forms of kawakawa or kavakava are also applied to the unrelated members of the genus Pittosporum. In other languages, such as Futunan, compound terms like kavakava atua refer to other species belonging to the genus Piper. The reduplication of the base form is indicative of falsehood or likeness, in the sense of "false kava".[21][16] In New Zealand, it was applied to the kawakawa (Piper excelsum) which is endemic to New Zealand and nearby Norfolk Island and Lord Howe Island. It was exploited by the Māori based on previous knowledge of the kava, as the latter could not survive in the colder climates of New Zealand. The Māori name for the plant, kawakawa, is derived from the same etymon as kava, but reduplicated. It is a sacred tree among the Māori people. It is seen as a symbol of death, corresponding to the rangiora (Brachyglottis repanda) which is the symbol of life. However, kawakawa has no psychoactive properties. Its connection to kava is clearly linked to its similarity in appearance and bitter taste.[21]

Characteristics

Kava was historically grown only in the Pacific islands of Hawaii, Federated States of Micronesia, Vanuatu, Fiji, the Samoas and Tonga. An inventory of P. methysticum distribution showed it was cultivated on numerous islands of Micronesia, Melanesia, Polynesia, and Hawaii, whereas specimens of P. wichmannii were all from Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu.[22]

The kava shrub thrives in loose, well-drained soils where plenty of air reaches the roots. It grows naturally where rainfall is plentiful, attaining over 78 inches (2,000 mm) per year. Ideal growing conditions are 70–95 °F (21–35 °C) and 70–100% relative humidity. Too much sunlight is harmful, especially in early growth, because kava is an understory crop.[23]

Kava cannot reproduce sexually. Female flowers are especially rare and do not produce fruit even when hand-pollinated. Its cultivation is entirely by propagation from stem cuttings.[24]

Traditionally, plants are harvested around four years of age, as older plants have higher concentrations of kavalactones. After reaching about 2 metres (6.6 ft) height, plants grow a wider stalk and additional stalks, but not much taller. The roots can reach a depth of 60 centimetres (2.0 ft).

Cultivars

Kava consists of sterile cultivars cloned from its wild ancestor, Piper wichmanii.[7] Today it comprises hundreds of different cultivars grown across the Pacific. Each cultivar has not only different requirements for successful cultivation, but also displays unique characteristics both in terms of its appearance, and in terms of its psychoactive properties.[7]

Noble and non-noble kava

Scholars make a distinction between the so-called "noble" and non-noble kava. The latter category comprises the so-called "tudei" (or "two-day") kavas, medicinal kavas, and wild kava (Piper wichmanii, the ancestor of domesticated Piper methysticum).[7][25] Traditionally, only noble kavas have been used for regular consumption, due to their more favourable composition of kavalactones and other compounds that produce more pleasant effects and have lower potential for causing negative side-effects, such as nausea or "kava hangover".[7][11]

The perceived benefits of noble cultivars explain why only these cultivars were spread around the Pacific by Polynesian and Melanesian migrants, with presence of non-noble cultivars limited to the islands of Vanuatu from which they originated.[7] More recently, it has been suggested that the widespread use of tudei cultivars in the manufacturing of several kava products might have been the key factor contributing to the rare reports of adverse reactions to kava observed among the consumers of kava-based products in Europe.[11]

Tudei varieties have traditionally not been grown in Hawaii and Fiji; but in recent years there have been reports of farmers attempting to grow "isa" or "palisi" non-noble cultivars in Hawaii, and of imports of dried tudei kava into Fiji for further re-exporting.[26] The tudei cultivars may be easier and cheaper to grow: while it takes up to 5 years for noble kava to mature, non-noble varieties can often be harvested just one year after being planted.

The concerns about the adverse effects of non-noble varieties, produced by their undesirable composition of kavalactones and high concentrations of potentially harmful compounds (flavokavains), which are not present in any significant concentration in the noble varieties, have led to legislation prohibiting exports from such countries as Vanuatu.[11] Likewise, efforts have been made to educate the non-traditional customers about the difference between noble and non-noble varieties and that non-noble varieties do not offer the same results as noble cultivars.[27][28] In recent years, government regulatory bodies and non-profit NGOs have been set up with the declared aim of monitoring kava quality, producing regular reports, certifying vendors selling proper, noble kava, and warning customers against products that may contain tudei varieties.[29]

Growing regions

In Vanuatu, exportation of kava is strictly regulated. Only cultivars classified as "noble" are allowed to be exported. Only the most desirable cultivars for everyday drinking are classified as noble to maintain quality control. In addition, their laws mandate that exported kava must be at least five years old and farmed organically. Their most popular noble cultivars are "Borogu" or "Borongoru" from Pentecost Island, "Melomelo" from Aoba Island (called Sese in the north Pentecost Island), and "Palarasul" kava from Espiritu Santo. In Vanuatu, Tudei ("two day") kava is reserved for special ceremonial occasions and exporting it is not allowed. "Palisi" is a popular Tudei variety.

In Hawaii, there are many other cultivars of kava (Hawaiian: ʻawa). Some of the most popular cultivars are Mahakea, Moʻi, Hiwa and Nene. The Aliʻi (kings) of precolonial Hawaii coveted the Moʻi variety, which had a strong cerebral effect due to a predominant amount of the kavalactone kavain. This sacred variety was so important to them that no one but royalty could ever experience it, "lest they suffer an untimely death". The reverence for Hiwa in old Hawaiʻi is evident in this portion of a chant recorded by Nathaniel Bright Emerson and quoted by E. S. Craighill and Elizabeth Green Handy. "This refers to the cup of sacramental ʻawa brewed from the strong, black ʻawa root (ʻawa hiwa) which was drunk sacramentally by the kumu hula":

The day of revealing shall see what it sees:

A seeing of facts, a sifting of rumors,

An insight won by the black sacred 'awa,

A vision like that of a god![30]

Winter describes a hula prayer for inspiration which contains the line, He ʻike pū ʻawa hiwa. Pukui and Elbert translated this as "a knowledge from kava offerings". Winter explains that ʻawa, especially of the Hiwa variety, was offered to hula deities in return for knowledge and inspiration.[30]

Relationship with kawakawa

.jpg.webp)

Kawakawa (Piper excelsum) plant, known also as "Māori kava", may be confused with kava. While the two plants look similar and have similar names, they are different but related species. Kawakawa is a small tree endemic to New Zealand, having importance to traditional medicine and Māori culture. As noted by the Kava Society of New Zealand, "in all likelihood, the kava plant was known to the first settlers of Aotearoa [New Zealand]. It is also possible that (just like the Polynesian migrants that settled in Hawaii) the Maori explorers brought some kava with them. Unfortunately, most of New Zealand is simply too cold for growing kava and hence the Maori settlers lost their connection to the sacred plant."[31] Further, "in New Zealand, where the climate is too cold for kava, the Maori gave the name kawa-kawa to another Piperaceae M. excelsum, in memory of the kava plants they undoubtedly brought with them and unsuccessfully attempted to cultivate. The Maori word kawa also means "ceremonial protocol", recalling the stylized consumption of the drug typical of Polynesian societies".[7] Kawakawa is commonly used in Maori traditional medicine for the treatment of skin infections, wounds and cuts, and (when prepared as a tea) for stomach upsets and other minor illnesses.[32]

Composition

Fresh kava root contains on average 80% water. Dried root contains approximately 43% starch, 20% dietary fiber, 15% kavalactones,[8] 12% water, 3.2% sugars, 3.6% protein, and 3.2% minerals.

In general, kavalactone content is greatest in the roots and decreases higher up the plant into the stems and leaves.[8] Relative concentrations of 15%, 10% and 5% have been observed in the root, stump, and basal stems, respectively.[6] The relative content of kavalactones depends not only on plant segment, but also on the kava plant varieties, plant maturity, geographic location, and time of harvest.[8] The kavalactones present are kavain, demethoxyyangonin and yangonin, which are higher in the roots than in the stems and leaves, with dihydrokavain, methysticin, and dihydromethysticin also present.[8]

The mature roots of the kava plant are harvested after a minimum of four years (at least five years ideally) for peak kavalactone content. Most kava plants produce around 50 kg (110 lb) of root when they are harvested. Kava root is classified into two categories: crown root (or chips) and lateral root. Crown roots are the large-diameter pieces that look like (1.5 to 5 inches (38 to 127 mm) diameter) wooden poker chips. Most kava plants consist of approximately 80% crown root upon harvesting. Lateral roots are smaller-diameter roots that look more like a typical root. A mature kava plant is about 20% lateral roots. Kava lateral roots have the highest content of kavalactones in the kava plant. "Waka" grade kava is made of lateral roots only.

Pharmacology

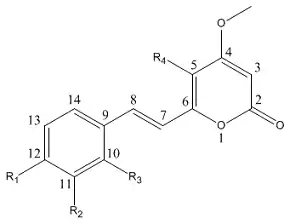

Constituents

A total of 18 different kavalactones (or kavapyrones) have been identified to date, at least 15 of which are active.[33] However, six of them, including kavain, dihydrokavain, methysticin, dihydromethysticin, yangonin, and desmethoxyyangonin, have been determined to be responsible for about 96% of the plant's pharmacological activity.[33] Some minor constituents, including three chalcones, flavokavain A, flavokavain B, and flavokavain C, have also been identified,[33] as well as a toxic alkaloid (not present in the consumable parts of the plant[34]), pipermethystine.[35] Alkaloids are present in the roots and leaves.[36]

Pharmacodynamics

The following pharmacological actions have been reported for kava and/or its major active constituents:[37]

- Potentiation of GABAA receptor activity (by kavain, dihydrokavain, methysticin, dihydromethysticin, and yangonin).

- Inhibition of the reuptake of norepinephrine (by kavain and methysticin) and possibly also of dopamine (by kavain and desmethoxyyangonin).

- Binding to the CB1 receptor (by yangonin).[38]

- Inhibition of voltage-gated sodium channels and voltage-gated calcium channels (by kavain and methysticin).

- Monoamine oxidase B reversible inhibition (by all six of the major kavalactones).

Receptor binding assays with botanical extracts have revealed direct interactions of leaf extracts of kava (which appear to be more active than root extracts) with the GABA (i.e., main) binding site of the GABAA receptor, the D2 receptor, the μ- and δ-opioid receptors, and the H1 and H2 receptors.[39][40] Weak interaction with the 5-HT6 and 5-HT7 receptors and the benzodiazepine site of the GABAA receptor was also observed.[39]

Potentiation of GABAA receptor activity may underlie the anxiolytic effects of kava, while elevation of dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens likely underlie the moderately psychotropic effects the plant can produce. Changes in the activity of 5-HT neurons could explain the sleep-inducing action[41] However, failure of the GABAA receptor inhibitor flumazenil to reverse the anxiolytic effects of kava in mice suggests that benzodiazepine-like effects are not contributing to the pharmacological profile of kava extracts.[42]

Heavy, long-term use of kava has been found to be free of association with reduced ability in saccade and cognitive tests, but has been associated with elevated liver enzymes.[43]

Detection

Recent usage of kava has been documented in forensic investigations by quantitation of kavain in blood specimens. The principal urinary metabolite, conjugated 4'-OH-kavain, is generally detectable for up to 48 hours.[44]

Preparations

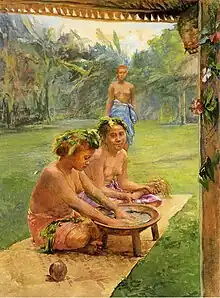

Traditional preparation

Kava is consumed in various ways throughout the Pacific Ocean cultures of Polynesia, Vanuatu, Melanesia and some parts of Micronesia and Australia. Traditionally, it is prepared by either chewing, grinding or pounding the roots of the kava plant. Grinding is done by hand against a cone-shaped block of dead coral; the hand forms a mortar and the coral a pestle. The ground root/bark is combined with only a little water, as the fresh root releases moisture during grinding. Pounding is done in a large stone with a small log. The product is then added to cold water and consumed as quickly as possible.

The extract is an emulsion of kavalactone droplets in starch and buttermilk. The taste is slightly pungent, while the distinctive aroma depends on whether it was prepared from dry or fresh plant, and on the variety. The colour is grey to tan to opaque greenish.

Kava prepared as described above is much more potent than processed kava. Chewing produces the strongest effect because it produces the finest particles. Fresh, undried kava produces a stronger beverage than dry kava. The strength also depends on the species and techniques of cultivation.

In Vanuatu, a strong kava drink is normally followed by a hot meal or tea. The meal traditionally follows some time after the drink so the psychoactives are absorbed into the bloodstream more quickly. Traditionally, no flavoring is added.

In Papua New Guinea, the locals in Madang province refer to their kava as waild koniak ("wild cognac" in English).

Fijians commonly share a drink called grog made by pounding sun-dried kava root into a fine powder, straining and mixing it with cold water. Traditionally, grog is drunk from the shorn half-shell of a coconut, called a bilo. Grog is very popular in Fiji, especially among young men, and often brings people together for storytelling and socializing. Drinking grog for a few hours brings a numbing and relaxing effect to the drinker; grog also numbs the tongue and grog drinking typically is followed by a "chaser" or sweet or spicy snack to follow a bilo.

Supplements and pharmaceutical preparations

Water extraction is the traditional method for preparation of the plant. Pharmaceutical and herbal supplement companies extract kavalactones from the kava plant using solvents such as supercritical carbon dioxide,[46] acetone, and ethanol to produce pills standardized with between 30% and 90% kavalactones.[29]

Concerns

Numerous scholars[47] and regulatory bodies[48][49] have raised concerns over the safety profile of such products.

One group of scholars say that organic solvents introduce compounds that may affect the liver into the standardized product; these compounds are not extracted by water and consequently largely absent from kava prepared with water.[50] For instance, when compared with water extraction, organic solvents extract vastly larger amounts of flavokavains, compounds associated with adverse reactions to kava that are present in very low concentrations in noble kava, but significant in non-noble.[51][11]

Also "chemical solvents used do not extract the same compounds as the natural water extracts in traditional use. The extraction process may exclude important modifying constituents soluble only in water".[50] In particular, it has been noted that, unlike traditional, water-based preparations, products obtained with the use of organic solvents do not contain glutathione, an important liver-protecting compound.[52] Another group of researchers noted: "The extraction process (aqueous vs. acetone in the two types of preparations) is responsible for the difference in toxicity as extraction of glutathione in addition to the kava lactones is important to provide protection against hepatotoxicity".[52]

It has also been argued that kavalactone extracts have often been made from low-quality plant material, including the toxic aerial parts of the plant, non-noble kava varieties, or plants affected by mold, which, in light of the chemical solvents' ability to extract far greater amounts of the potentially toxic compounds than water, makes them particularly problematic.

In the context of these concerns, the World Health Organization advises against the consumption of ethanolic and acetonic kavalactone extracts, and says that "products should be developed from water-based suspensions of kava".[49] The government of Australia prohibit the sales of such kavalactone extracts, and only permit the sale of kava products in their natural form or produced with cold water.[53]

Kava culture

Kava is used for medicinal, religious, political, cultural, and social purposes throughout the Pacific. These cultures have a great respect for the plant and place a high importance on it. In Fiji, for example, a formal yaqona (kava) ceremony will often accompany important social, political, or religious functions, usually involving a ritual presentation of the bundled roots as a sevusevu (gift), and drinking of the yaqona itself.[54][55] Due to the importance of kava in religious rituals and the seemingly (from the Western point of view) unhygienic preparation method, its consumption was discouraged or even banned by Christian missionaries.[7]

Kava bars

With kava's increasing popularity, bars serving the plant in its liquid state are beginning to open up outside of the South Pacific.[11][56]

A 2010 review concluded that it's possible that ethanol combined with kava may be the cause of kava hepatotoxicity.[57] While some bars have been committed to only serving the traditional forms and types of kava, other establishments have been accused of serving non-traditionally consumed non-noble kava varieties which are cheaper, but far more likely to cause unpleasant effects and adverse reactions, or of serving kava with other substances, including alcohol.[58]

Effects of consumption

The nature of effects will largely depend on the cultivar of the kava plant and the form of its consumption.[59] Traditionally, only noble kava cultivars have been consumed as they are accepted as safe and produce desired effects.[60] The specific effects of various noble kavas depend on various factors, such as the cultivar used (and the related specific composition of kavalactones), age of the plant, and method of its consumption.[59] However, it can be stated that in general noble kava produces a state of calmness, relaxation and well-being without diminishing cognitive performance.[7][61][62] Kava may produce an initial talkative period, followed by muscle relaxation and eventual sleepiness.[63]

As noted in one of the earliest Western publications on kava (1886): "A well prepared Kava potion drunk in small quantities produces only pleasant changes in behavior. It is therefore a slightly stimulating drink which helps relieve great fatigue. It relaxes the body after strenuous efforts, clarifies the mind and sharpens the mental faculties".[64]

According to contemporary descriptions:

Kava seizes one's mind. This is not a literal seizure, but something does change in the processes by which information enters, is retrieved, or leads to actions as a result. Thinking is certainly affected by the kava experience, but not in the same ways as are found from caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, or marijuana. I would personally characterize the changes I experienced as going from lineal processing of information to a greater sense of "being" and contentment with being. Memory seemed to be enhanced, whereas restriction of data inputs was strongly desired, especially with regard to disturbances of light, movements, noise and so on. Peace and quiet were very important to maintain the inner sense of serenity. My senses seemed to be unusually sharpened, so that even whispers seemed to be loud while loud noises were extremely unpleasant.[7]

When the mixture is not too strong, the subject attains a state of happy unconcern, well-being and contentment, free of physical or psychological excitement. At the beginning conversation comes in a gentle, easy flow and hearing and sight are honed, becoming able to perceive subtle shades of sound and vision. Kava soothes temperaments. The drinker never becomes angry, unpleasant, quarrelsome or noisy, as happens with alcohol. Both natives and whites consider kava as a means of easing moral discomfort. The drinker remains master of his conscience and reason.[7]

...In the late afternoon, a large museum crew would retire en masse to one of the many kava bars; kava, the national ritual drink, is a relaxing tonic of a cloudy green, which you drink from a miso-bowl "shell" in the solitude of a shadow. Unlike traditional bars, which tend to become louder and more volatile as people drink, kava bars tend to get quieter and calmer as the evening fades to black – until practically the only sounds are the screech of the native fruit bat.[65]

Despite its psychoactive effects, kava is not considered to be physically addictive and its use does not lead to dependency.[66][67]

Adverse drug interactions

Kava taken in combination with alprazolam can cause a semicomatose state in humans.[68]

Research

A 2010 review concluded that it's possible that ethanol combined with kava may be the cause of kava hepatotoxicity.[57]

Toxicity, safety, and potential side effects

General observations

A 2016 comprehensive review of kava safety conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) concluded that: "On balance, the weight-of-evidence from both a long history of use of kava beverage and from the more recent research findings indicates that it is possible for kava beverage to be consumed with an acceptably low level of health risk".[10] The authors of the review noted that:

Kava beverage has a long history of consumption in the South Pacific and has an important role in traditional community ceremonies. In recent times, it has become more widely consumed as a recreational beverage in both the South Pacific islander community as well as in the wider international community. Within these communities, kava is considered to be a safe and enjoyable beverage, based on a long tradition of use and little evidence of harm. There is little documented evidence of adverse health effects associated with traditional moderate levels of consumption of kava beverage, with only anecdotal reports of general symptoms of lethargy and headaches. Whether this reflects genuine low incidence or an under-reporting of adverse health effects is unclear. Clinical trials examining the efficacy of aqueous extracts of kava in treating anxiety, although limited, have also not identified adverse health effects.[10]

At the same time, it was observed that:

On the other hand, there is strong evidence that high levels of consumption of kava beverage can result in scaly skin rash, weight loss, nausea, loss of appetite and indigestion. These adverse health effects, while significant, are considered to be reversible upon cessation of kava use. Other possible effects include sore red eyes, laziness, loss of sex drive and general poor health. No effect on cognition, which might be associated with the pharmacological activity of kava, has been identified. No information is available on the potential for kava beverage consumption to impact on the incidence of chronic disease. Moderate to high kava beverage consumption also produces a reversible increase in the liver enzyme gamma glutamyltransferase (GGT), which may be an early indicator of cholestasis. Clinical surveys in Aboriginal communities in northern Australia with a history of heavy kava use have not revealed any evidence of long-term liver damage associated with consumption of kava beverage.[10]

A human health risk assessment conducted by the Australian and New Zealand governments concluded that:

The available data indicates that traditional kava beverage prepared from the root has a long tradition of safe use in the South Pacific Islands. It is compositionally different from kava products prepared by extraction using organic solvents. While excessive consumption of the traditional kava beverage may lead to adverse health effects, such as kava dermopathy [see below], there is no evidence that occasional use of kava beverage is associated with any long-term adverse effects. (...) The available data (...) does not suggest any specific health problems associated with moderate use of kava beverage.[48]

A 2013 overview of 50 systematic reviews listed the pyper methysticum among the only four of the 50 monitored herbal medicines which showed serious adverse effects for the human health.[69]

Effects on the liver

According to a 2010 discussion paper prepared for the Codex Alimentarius Commission: "kava has had at least a 1500-year history of relatively safe use, with liver side effects never having arisen in the ethnopharmacological data. (...) Clinical trials of kava have not revealed hepatotoxicity as a problem. This has been confirmed by further studies evaluating the toxicology of kava drink. Based on available scientific information it can be inferred that kava as a traditional beverage is safe for human consumption."[70]

In 2001, concerns were raised about the safety of kava, which led to restrictions and regulations in several countries,[33] as well as reports by the United States CDC[71] and FDA.[72] In response to media reports from Europe, in 2002 the FDA issued a (now archived) Consumer Advisory stating that, "Kava-Containing Dietary Supplements May be Associated With Severe Liver Injury."[73] Likewise, LiverTox of the National Library of Medicine/National Institutes of Health noted that: "The frequency of adverse reactions to kava, particularly liver injury, is not known... Between 50 and 100 cases of clinically apparent liver injury have been published or discussed in the literature. Advocates for the herb have strongly rejected these numbers, disputing both their accuracy and the causality assessment process. Still, there seems to be convincing evidence in some cases of severe hepatitis ending in fulminant hepatic failure, requiring liver transplantation, and even leading to death."[74]

Most of the concerns were related to a small number of reports indicating potential cases of hepatotoxicity caused by consumption of various commercial products derived from kava. A number of scientists and medical practitioners criticized the poor quality of the reports by pointing out that most of the reported rare cases of hepatotoxicity involved patients with a history of alcohol or prescription drug abuse or concomitant use of medicines known as potentially hepatotoxic.[75] Likewise, the Australian studies from the late 1990s suggesting an association between health problems and heavy kava use,[76] that contributed toward the rise of concerns about kava were found to be focused on populations with very heavy concomitant consumption of alcohol and overall poor health. More rigorous clinical research has found no evidence of any significant negative health issues (including any irreversible liver damage) that could be linked to kava.[77] In light of this information and subsequent research[11] on 10 June 2014, the German Administrative Court overturned the 2002 ban reinstating the regulatory requirements of 2001. The court stated that risk from kava exposure had not been clearly demonstrated, nor does it appear unusually high, an opinion presumably driven by the very small number of cases of reported toxicity (n ~ 3) with even a certain degree of causality linked to kava in a global kava-consuming community that may number in the millions of doses consumed daily.[12]

According to one comprehensive review: "Despite the link to kava and liver toxicity demonstrated in vivo and in vitro, in the history of Western kava use, toxicity is still considered relatively rare. Only a fraction of the handful of cases reviewed for liver toxicity could be, with any certainty, linked to kava consumption and most of those involved the co-ingestion of other medications/supplements. That means that the incident rate of liver toxicity due to kava is one in 60–125 million patients."[12] According to an in-depth human health risk assessment commissioned by the New Zealand and Australian governments, while consumption of kava may result in such minor and reversible side effects as kava dermopathy (see below), "there is no evidence that occasional use of kava beverage is associated with any long-term adverse effects, including effects on the liver."[48]

Aside from "the small number of cases of kava hepatotoxicity [that might have been] due to an idiosyncratic reaction of the metabolic type",[78] "liver injury by kava is basically a preventable disease".[79] In order to minimize or eliminate the risk of liver injury, only high-quality plant material should be used in the preparation of kava supplements or kava beverages.[29] In particular, the use of the so-called "two-day" (known also as "tudei", "isa", "palisi") and wild (Piper wichmanii) cultivars traditionally not consumed, should be avoided.[11] The use of these cultivars in the manufacturing of kava-based pharmaceutical products is undesirable due to their very different phytochemistry and relatively high concentrations of potentially harmful compounds (flavokavains).[11][60] While other ("noble") cultivars also contain these compounds, toxicity seems to be triggered only at relatively high concentrations, too high to be of relevance with the use of noble kava or its corresponding extract preparations".[11] Such cultivars mainly grow in Vanuatu, which outlawed their exports in 2004.[25]

Other adverse reactions

Adverse reactions may result from the poor quality of kava raw material used in the manufacturing of various kava products.[29][36][79][47] In addition to the potential for hepatotoxicity, adverse reactions from chronic use may include visual impairment, rashes or dermatitis, seizures, weight loss, and malnutrition, but there is only limited high-quality research on these possible effects.[10][36]

On the basis of research findings and long history of safe use across the South Pacific, experts recommend using water-based extractions of high-quality peeled rhizome and roots of the noble kava cultivars to minimize the potential of adverse reactions to chronic use.[10][29]

Potential interactions

Several adverse interactions with drugs have been documented, both prescription and nonprescription – including, but not limited to, anticonvulsants, alcohol, anxiolytics (CNS depressants such as benzodiazepines), antipsychotics, levodopa, diuretics, and drugs metabolized by CYP450 in the liver.[36]

A few notable potential drug interactions are, but are not limited to:

- Alcohol: It has been reported that combined use of alcohol and kava extract can have additive sedative effects.[36][80] Regarding cognitive function, kava has been shown to have additive cognitive impairments while taken with alcohol when compared to taking placebo and alcohol alone.[81]

- Anxiolytics (CNS depressants such as benzodiazepines and barbiturates): Kava may have potential additive CNS depressant effects (such as sedation and anxiolytic effects) with benzodiazepines and barbiturates.[36][81]

- Dopamine agonist – levodopa: One of levodopa's chronic side effects that Parkinson's patients experience is the "on-off phenomenon" of motor fluctuations where there will be periods of oscillations between "on" where the patient experiences symptomatic relief and "off" where the therapeutic effect wears off early.[82] When taking levodopa and kava together, it has been shown that there is an increased frequency of this "on-off phenomenon".[83]

Kava dermopathy

Long term and heavy kava consumption is associated with a reversible skin condition known as "kava dermopathy" or kanikani (in the Fijian language), characterised by dry and scaly skin covering the palms of the hands, soles of the feet, and back.[36][84][85] The first symptom to appear usually is dry, peeling skin; some Pacific Islanders deliberately consume large quantities of kava for several weeks in order to get the peeling effect, resulting in a layer of new skin.[86] These effects appeared at consumption levels between 31 grams (1.1 oz) to 440 grams (0.97 lb) a week of kava powder. Despite numerous studies, the mechanism that causes kava dermopathy is poorly understood "but may relate to interference with cholesterol metabolism".[85] The condition is easily treatable with abstinence or lowering of kava intake as the skin appears to be returning to its normal state within a couple of weeks of reduced or no kava use.[85] Kava dermopathy should not be confused with rare instances of allergic reactions to kava that are usually characterised by itchy rash or puffy face.[87]

Research

Kava is under preliminary research for its potential psychoactive[33] – primarily anxiolytic – sleep-inducing, and sleep-enhancing properties.[88] Preliminary randomized controlled trials in anxiety disorders indicate a higher rate of improvement in anxiety symptoms after kava treatment, relative to placebo.[89]

Traditional medicine

Over centuries, kava has been used in the traditional medicine of the South Pacific Islands for central nervous system and peripheral effects.[90] As noted in one literature review: "Peripherally, kava is indicated in traditional Pacific medicine for urogenital conditions (gonorrhea infections, chronic cystitis, difficulty urinating), reproductive and women's health (...), gastrointestinal upsets, respiratory ailments (asthma, coughs, and tuberculosis), skin diseases and topical wounds, and as an analgesic, with significant subtlety and nuance attending the precise strain, plant component (leaf, stem, root) and preparative method to be used".[90]

Regulation

Kava remains legal in most countries. Regulations often treat it as a food or dietary supplement.

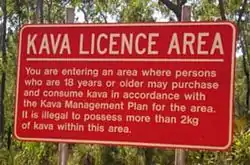

Australia

In Australia, the supply of kava is regulated through the National Code of Kava Management.[91] Travellers to Australia are allowed to bring up to 4 kg of kava in their baggage, provided they are at least 18 years old, and the kava is in root or dried form. Commercial import of larger quantities is allowed, under licence for medical or scientific purposes. These restrictions were introduced in 2007 after concern about abuse of kava in indigenous communities. Initially, the import limit was 2 kg per person; it was raised to 4 kg in December 2019, and a pilot program allowing for commercial importation was implemented on 1 December 2021.[92][93]

The Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration has recommended no more than 250 mg of kavalactones be taken in a 24‑hour period.[94]

Kava possession is limited to 2 kg per adult in the Northern Territory.[95][96] While it was banned in Western Australia previously in the 2000s, the Western Australian Health Department announced lifting of its ban in February 2017, bringing Western Australia "into line with other States" where it has always remained legal, albeit closely regulated.[97]

Europe

Following the discussions on the safety of certain pharmaceutical products derived from kava and sold in Germany, in 2002 the EU imposed a temporary ban on imports of kava-based pharmaceutical products. The sale of kava plant became regulated in Switzerland, France, and in prepared form in the Netherlands.[98] Some Pacific Island States who had been benefiting from the export of kava to the pharmaceutical companies have attempted to overturn the EU ban on kava-based pharmaceutical products by invoking international trade agreements at the WTO: Fiji, Samoa, Tonga and Vanuatu argued that the ban was imposed with insufficient evidence.[99] The pressure prompted Germany to reconsider the evidence base for banning kava-based pharmaceutical products.[100] On 10 June 2014, the German Administrative Court overturned the 2002 ban making selling kava as a medicine legal (personal possession of kava has never been illegal), albeit strictly regulated. In Germany, kava-based pharmaceutical preparations are currently prescription drugs. Furthermore, patient and professional information brochures have been redesigned to warn about potential side effects.[101] These strict measures have been opposed by some of the leading kava scientists. In early 2016 a court case has been filed against the Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte (BfArM/German Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices) arguing that the new regulatory regime is too strict and not justified.[102]

In the United Kingdom it is a criminal offence to sell, supply or import any medicinal product containing kava for human consumption.[103] It is legal to possess kava for personal use, or to import it for purposes other than human consumption (e.g. for animals).

Until August 2018, Poland was the only EU country with an "outright ban on kava" and where the mere possession of kava was prohibited and may have resulted in a prison sentence.[104] Under the new legislation, kava is no longer listed among prohibited substances and it is therefore legal to possess, import and consume the plant,[105] but it remains illegal to sell it within Poland for the purpose of human consumption.[106]

In the Netherlands, for unknown reasons, the ban was never lifted and it is still prohibited to prepare, manufacture or trade kava or goods containing kava.[107]

New Zealand

When used traditionally, kava is regulated as a food under the Food Standards Code. Kava may also be used as an herbal remedy, where it is currently regulated by the Dietary Supplements Regulations. Only traditionally consumed forms and parts of the kava plant (i.e., pure roots of the kava plant, water extractions prepared from these roots) can legally be sold as food or dietary supplements in New Zealand. The aerial parts of the plant (growing up and out of the ground), unlike the roots, contain relatively small amounts of kavalactones; instead, they contain a mildly toxic alkaloid pipermethysticine.[48] While not normally consumed, the sale of aerial plant sections and non-water based extract (such as CO2, acetonic or ethanol extractions) is prohibited for the purpose of human consumption (but can be sold as an ingredient in cosmetics or other products not intended for human consumption).[108][109]

North America

In 2002, Health Canada issued an order prohibiting the sale of any product containing kava.[110] While the restrictions on kava were lifted in 2012,[111] Health Canada lists five kava ingredients as of 2017.[112][113]

In 2002, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a Consumer Advisory: "Kava-Containing Dietary Supplements May be Associated With Severe Liver Injury." No legal action was taken and this advisory has since been archived.[114]

Vanuatu

The Pacific island-state of Vanuatu has passed legislation to regulate the quality of its kava exports. Vanuatu prohibits the export or consumption of non-noble kava varieties or the parts of the plant that are unsuitable for consumption (such as leaves and stems).[115]

See also

References

- "Kava". Merriam–Webster Online Dictionary. 2018.

- "Nā Puke Wehewehe ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi". wehewehe.org. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- Fitisemanu, Jacob (2007) Samoan social drinking: perpetuation and adaptation of ʻAva ceremonies in Salt Lake County, Utah B. A. Thesis, Westminster College p. 2.

- "Embassy of the Republic of Fiji". www.fijiembassy.be. Archived from the original on 10 June 2018. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- Balick, Michael J. and Leem, Roberta (2002) Traditional use of sakau (kava) in Pohnpei: lessons for integrative medicine Alternative Therapies, Vol. 8, No.4. p. 96

- Lebot, Vincent; Merlin, Mark; Lindstrom, Lamont (23 December 1992). Kava. Yale University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt211qwxb. ISBN 9780300238983.

- Lebot, Vincent; Merlin, Mark; Lindstrom, Lamont (1997). Kava: The Pacific Elixir: The Definitive Guide to Its Ethnobotany, History, and Chemistry. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-89281-726-9.

- Wang, J; Qu, W; Bittenbender, H. C; Li, Q. X (2013). "Kavalactone content and chemotype of kava beverages prepared from roots and rhizomes of Isa and Mahakea varieties and extraction efficiency of kavalactones using different solvents". Journal of Food Science and Technology. 52 (2): 1164–1169. doi:10.1007/s13197-013-1047-2. PMC 4325077. PMID 25694734.

- Pittler MH, Ernst E (2003). Pittler, Max H (ed.). "Kava extract for treating anxiety". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD003383. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003383. PMC 6999799. PMID 12535473.

- "Kava: a review of the safety of traditional and recreational beverage consumption" (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and World Health Organization, Rome, Italy. 2016.

- Kuchta, Kenny; Schmidt, Mathias; Nahrstedt, Adolf (1 December 2015). "German Kava Ban Lifted by Court: The Alleged Hepatotoxicity of Kava (Piper methysticum) as a Case of Ill-Defined Herbal Drug Identity, Lacking Quality Control, and Misguided Regulatory Politics". Planta Medica. 81 (18): 1647–1653. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1558295. ISSN 1439-0221. PMID 26695707. S2CID 23708406.

- Showman, A. F.; Baker, J. D.; Linares, C; Naeole, C. K.; Borris, R; Johnston, E; Konanui, J; Turner, H (2015). "Contemporary Pacific and Western perspectives on 'awa (Piper methysticum) toxicology". Fitoterapia. 100: 56–67. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2014.11.012. PMID 25464054.

- Applequist, Wendy L.; Lebot, Vincent (25 April 2006). "Validation of Piper Methysticum var. wichmannii (Piperaceae)". Novon: A Journal for Botanical Nomenclature. 16 (1): 3–4. doi:10.3417/1055-3177(2006)16[3:VOPMVW]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 86552278.

- Ross, Malcolm (2008). "Other cultivated plants". In Ross, Malcolm; Pawley, Andrew; Osmond, Meredith (eds.). The lexicon of Proto Oceanic: The culture and environment of ancestral Oceanic society. Vol. 3. Pacific Linguistics. pp. 389–426. ISBN 9780858835894.

- Lebot, V.; Lèvesque, J. (1989). "The Origin and Distribution of Kava (Piper methysticum Forst. F., Piperaceae): A Phytochemical Approach". Allertonia. 5 (2): 223–281.

- "*Kava ~ *Kavakava". Te Mära Reo: The Language Garden. Benton Family Trust. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- Blust, Robert; Trussel, Stephen (2013). "The Austronesian Comparative Dictionary: A Work in Progress". Oceanic Linguistics. 52 (2): 493–523. doi:10.1353/ol.2013.0016. S2CID 146739541.

- Lynch, John (2002). "Potent Roots and the Origin of kava". Oceanic Linguistics. 41 (2): 493–513. doi:10.1353/ol.2002.0010. S2CID 145424062.

- Heathcote, Gary M.; Diego, Vincent P.; Ishida, Hajime; Sava, Vincent J. (2012). "An osteobiography of a remarkable protohistoric Chamorro man from Taga, Tinian". Micronesica. 43 (2): 131–213.

- McLean, Mervyn (2014). Music, Lapita, and the Problem of Polynesian Origins. Polynesian Origins. ISBN 9780473288730.

- "Kawa ~ Kawakawa". Te Mära Reo: The Language Garden. Benton Family Trust. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- Vincent Lebot; Patricia Siméoni (2004). "Is the Quality of Kava (Piper methysticum Forst. f.) Responsible for Different Geographical Patterns?" (PDF). Ethnobotany Research & Applications. 2: 19–28. doi:10.17348/era.2.0.19-28.

- Amiri Tasi (7 February 2020). "Botany of the Kava Plant". Kava Guides. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- "Notes on Propagating Traditional Hawaiian Plants". FoodPlant Tropics. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- Teschke, Rolf; Lebot, Vincent (1 October 2011). "Proposal for a Kava Quality Standardization Code". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 49 (10): 2503–2516. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2011.06.075. PMID 21756963.

- "Drink the right mix - Fiji Times Online". www.fijitimes.com. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- "Vanuatu hopes for kava export growth". Radio New Zealand. 11 November 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- "Vanuatu kava cleared for European market". Radio New Zealand. 12 November 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- Teschke, Rolf; Sarris, Jerome; Lebot, Vincent (15 January 2011). "Kava hepatotoxicity solution: A six-point plan for new kava standardization". Phytomedicine. 18 (2–3): 96–103. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2010.10.002. PMID 21112196.

- Johnston, Ed; Rogers, Helen; Association for Hawaiian ʻAwa (1 January 2006). Hawaiian ʻawa: views of an ethnobotanical treasure (PDF). Hilo, Hawaii: Association for Hawaiian ʻAwa. p. 34. OCLC 77501873.

- "Kava vs Kawakawa | Kava use in New Zealand | Maori Memories of Kava". kavasociety.nz. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- "Māori Plant Use Database Plant Use Details of Macropiper excelsum". maoriplantuse.landcareresearch.co.nz. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- Sarris J, LaPorte E, Schweitzer I (2011). "Kava: a comprehensive review of efficacy, safety, and psychopharmacology". Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 45 (1): 27–35. doi:10.3109/00048674.2010.522554. PMID 21073405. S2CID 42935399.

- Bunchorntavakul, C.; Reddy, K. R. (1 January 2013). "Review article: herbal and dietary supplement hepatotoxicity". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 37 (1): 3–17. doi:10.1111/apt.12109. ISSN 1365-2036. PMID 23121117. S2CID 6949220.

- Olsen LR, Grillo MP, Skonberg C (2011). "Constituents in kava extracts potentially involved in hepatotoxicity: a review". Chem. Res. Toxicol. 24 (7): 992–1002. doi:10.1021/tx100412m. PMID 21506562.

- "Kava". Drugs.com. 3 January 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- Singh YN, Singh NN (2002). "Therapeutic potential of kava in the treatment of anxiety disorders". CNS Drugs. 16 (11): 731–43. doi:10.2165/00023210-200216110-00002. PMID 12383029. S2CID 34322458.

- Ligresti A, Villano R, Allarà M, Ujváry I, Di Marzo V (2012). "Kavalactones and the endocannabinoid system: the plant-derived yangonin is a novel CB₁ receptor ligand". Pharmacol. Res. 66 (2): 163–9. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2012.04.003. PMID 22525682.

- Dinh LD, Simmen U, Bueter KB, Bueter B, Lundstrom K, Schaffner W (2001). "Interaction of various Piper methysticum cultivars with CNS receptors in vitro". Planta Med. 67 (4): 306–11. doi:10.1055/s-2001-14334. PMID 11458444. S2CID 260281694.

- Amitava Dasgupta; Catherine A. Hammett-Stabler (2011). Herbal Supplements: Efficacy, Toxicity, Interactions with Western Drugs, and Effects on Clinical Laboratory Tests. John Wiley & Sons. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-470-92275-0.

- Baum SS, Hill R, Rommelspacher H (1998). "Effect of kava extract and individual kavapyrones on neurotransmitter levels in the nucleus accumbens of rats". Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 22 (7): 1105–20. doi:10.1016/s0278-5846(98)00062-1. PMID 9829291. S2CID 24377397.

- Garrett KM, Basmadjian G, Khan IA, Schaneberg BT, Seale TW (2003). "Extracts of kava (Piper methysticum) induce acute anxiolytic-like behavioral changes in mice". Psychopharmacology. 170 (1): 33–41. doi:10.1007/s00213-003-1520-0. PMID 12845414. S2CID 10805207.

- Cairney S, Clough AR, Maruff P, Collie A, Currie BJ, Currie J (2003). "Saccade and cognitive function in chronic kava users". Neuropsychopharmacology. 28 (2): 389–96. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300052. PMID 12589393.

- R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 803–804.

- "Fiji -> In depth -> Food and Drink". www.frommers.com. Frommers. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- Viorica, Lopez-Aila (1997). "Supercritical fluid extraction of kava lactones from Piper methysticum (kava) herb". Journal of High Resolution Chromatography. 20 (10): 555–559. doi:10.1002/jhrc.1240201007.

- Teschke, Rolf; Sarris, Jerome; Glass, Xaver; Schulze, Johannes (2016). "Kava, the anxiolytic herb: back to basics to prevent liver injury?". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 71 (3): 445–448. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03775.x. ISSN 0306-5251. PMC 3045554. PMID 21284704.

- "Kava: A Human Health Risk Assessment" (PDF). Technical Report Series No 30. 25 May 2016.

- Organization, World Health (2007). Assessment of the Risk of Hepatotoxicity with Kava Products. WHO Regional Office Europe. ISBN 9789241595261.

- Kraft, M; Spahn, T W; Menzel, J; Senninger, N; Dietl, K.-H; Herbst, H; Domschke, W; Lerch, M M (2001). "Fulminantes Leberversagen nach Einnahme des pflanzlichen Antidepressivums Kava-Kava". Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift. 126 (36): 970–972. doi:10.1055/s-2001-16966. ISSN 0012-0472. PMID 11544547. S2CID 260067545.

- Zhou, Ping; Gross, Shimon; Liu, Ji-Hua; Yu, Bo-Yang; Feng, Ling-Ling; Nolta, Jan; Sharma, Vijay; Piwnica-Worms, David; Qiu, Samuel X. (December 2010). "Flavokawain B, the hepatotoxic constituent from kava root, induces GSH-sensitive oxidative stress through modulation of IKK/NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways". The FASEB Journal. 24 (12): 4722–4732. doi:10.1096/fj.10-163311. ISSN 0892-6638. PMC 2992378. PMID 20696856.

- Whitton, Peter A; Lau, Andrew; Salisbury, Alicia; Whitehouse, Julie; Evans, Christine S (1 October 2003). "Kava lactones and the kava-kava controversy". Phytochemistry. 64 (3): 673–679. Bibcode:2003PChem..64..673W. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(03)00381-9. ISSN 0031-9422. PMID 13679089.

- Health. "Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code - Standard 2.6.3 - Kava". www.legislation.gov.au. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- Biturogoiwasa, Solomoni; Walker, Anthony R. (2001). My Village, My World: Everyday Life in Nadoria, Fiji. Suva, Fiji: Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific. pp. 17–20. ISBN 978-982-02-0160-6.

- Tomlinson, Matt (2007). "Everything and Its Opposite: Kava Drinking in Fiji". Anthropological Quarterly. 80 (4): 1065–81. doi:10.1353/anq.2007.0054. S2CID 144600224.

- Laterman, Kaya (22 December 2017). "In Brooklyn, a Hare Krishna Reckoning". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- Li, XZ; Ramzan, I (April 2010). "Role of ethanol in kava hepatotoxicity". Phytotherapy Research. 24 (4): 475–80. doi:10.1002/ptr.3046. PMID 19943335. S2CID 35975791.

- Swanson, Jess (20 March 2014). "South Florida Kava Bars Unworried about Two-Day Kava". Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- Kilham, Christopher (1 June 1996). Kava: Medicine Hunting in Paradise: The Pursuit of a Natural Alternative to Anti-Anxiety Drugs and Sleeping Pills. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. ISBN 9780892816408.

- Lebot, V.; Do, T. K. T.; Legendre, L. (15 May 2014). "Detection of flavokavins (A, B, C) in cultivars of kava (Piper methysticum) using high performance thin layer chromatography (HPTLC)". Food Chemistry. 151: 554–560. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.11.120. ISSN 0308-8146. PMID 24423570.

- Cairney, Sheree; Clough, Alan R; Maruff, Paul; Collie, Alex; Currie, Bart J; Currie, Jon (14 February 2003). "Saccade and Cognitive Function in Chronic Kava Users". Neuropsychopharmacology. 28 (2): 389–396. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300052. ISSN 0893-133X. PMID 12589393.

- LaPorte, E.; Sarris, J.; Stough, C.; Scholey, A. (1 March 2011). "Neurocognitive effects of kava (Piper methysticum): a systematic review". Human Psychopharmacology. 26 (2): 102–111. doi:10.1002/hup.1180. ISSN 1099-1077. PMID 21437989. S2CID 44657320.

- Baker, Jonathan D. (1 June 2011). "Tradition and toxicity: evidential cultures in the kava safety debate". Social Studies of Science. 41 (3): 361–384. doi:10.1177/0306312710395341. ISSN 0306-3127. PMID 21879526. S2CID 33364504.

- Kilham, Christopher S. (1 June 1996). Kava: Medicine Hunting in Paradise: The Pursuit of a Natural Alternative to Anti-Anxiety Drugs and Sleeping Pills. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. ISBN 9781620550342.

- Lewis-Kraus, Gideon, I Traveled to Vanuatu, an Island Nation in the South Pacific, to Report on Discoveries in Ancient DNA, The New York Times, nyt mag, Thursday, 17 January 2019

- Lebot, V.; Lèvesque, J. (1 January 1989). "The origin and distribution of kava (Piper methysticum Forst. F., Piperaceae): A phytochemical approach". Allertonia. 5 (2): 223–281. JSTOR 23187398.

- Sarris, J.; Stough, C.; Teschke, R.; Wahid, Z. T.; Bousman, C. A.; Murray, G.; Savage, K. M.; Mouatt, P.; Ng, C. (1 November 2013). "Kava for the Treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder RCT: Analysis of Adverse Reactions, Liver Function, Addiction, and Sexual Effects". Phytotherapy Research. 27 (11): 1723–1728. doi:10.1002/ptr.4916. ISSN 1099-1573. PMID 23348842. S2CID 19526418.

- Hu, Z; Yang, X; Ho, PC; Chan, SY; Heng, PW; Chan, E; Duan, W; Koh, HL; Zhou, S (2005). "Herb-drug interactions: a literature review". Drugs. 65 (9): 1239–82. doi:10.2165/00003495-200565090-00005. PMID 15916450. S2CID 46963549.

- Paul Posadzki; Leala K Watson; Edzard Ernst (2013). "Adverse effects of herbal medicines: an overview of systematic reviews". Clinical Medicine. 13 (1): 7–12. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.13-1-7. PMC 5873713. PMID 23472485.

- "Discussion paper on the development of a standard for kava" (PDF). Codex Alimentarius Commission, United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization and World Health Organization. 1 October 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2018. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2002). "Hepatic Toxicity Possibly Associated with Kava-Containing Products – United States, Germany, and Switzerland, 1999 2002". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 51 (47): 1065–1067. PMID 12500906. Retrieved 16 September 2005.

- "Consumer Advisory: Kava-Containing Dietary Supplements May Be Associated with Severe Liver Injury". Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition. 25 March 2002. Archived from the original on 25 March 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2005.

- "Consumer Advisory: Kava-Containing Dietary Supplements May be Associated With Severe Liver Injury". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 25 March 2002.

- "Kava kava". National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Bethesda, MD. 6 December 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- Baker, Jonathan (2011). "Tradition and toxicity: Evidential cultures in the kava safety debate". Social Studies of Science. 41 (3): 361–384. doi:10.1177/0306312710395341. JSTOR 41301937. PMID 21879526. S2CID 33364504.

- "National Drug Strategy - Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Complementary Action Plan 2003–2009 - Background Paper" Archived 5 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy, Commonwealth of Australia, May 2006. ISBN 0 642 82328 6.

- Clough, Alan R.; Bailie, Ross S.; Currie, Bart (1 January 2003). "Liver Function Test Abnormalities in Users of Aqueous Kava Extracts". Journal of Toxicology: Clinical Toxicology. 41 (6): 821–829. doi:10.1081/CLT-120025347. ISSN 0731-3810. PMID 14677792. S2CID 40161690.

- Teschke, Rolf; Sarris, Jerome; Schweitzer, Isaac (2012). "Kava hepatotoxicity in traditional and modern use: The presumed Pacific kava paradox hypothesis revisited". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 73 (2): 170–4. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04070.x. PMC 3269575. PMID 21801196.

- Teschke, Rolf; Schulze, Johannes (2010). "Risk of Kava Hepatotoxicity and the FDA Consumer Advisory". JAMA. 304 (19): 2174–5. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1689. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 21081732.

- Cairney S.; Maruff P.; Clough A. R.; Collie A.; Currie J.; Currie B. J. (2003). "Saccade and cognitive impairment associated with kava intoxication". Hum. Psychopharmacol. 18 (7): 525–533. doi:10.1002/hup.532. PMID 14533134. S2CID 21555220.

- Spinella M (2002). "The importance of pharmacological synergy in psychoactive herbal medicines". Altern Med Rev. 7 (2): 130–137. PMID 11991792.

- Lees AJ (1989). "The on-off phenomenon". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. Suppl (9): 29–37. doi:10.1136/jnnp.52.suppl.29. PMC 1033307. PMID 1033307.

- Izzo AA, Ernst E. Interactions between herbal medicines and prescribed drugs: a systematic review" Drugs 2001;61(15):2163-75.

- Ruze, P. (16 June 1990). "Originally published as Volume 1, Issue 8703Kava-induced dermopathy: a niacin deficiency?". The Lancet. 335 (8703): 1442–1445. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(90)91458-M. PMID 1972218. S2CID 9737032.

- Norton, Scott A.; Ruze, Patricia (1 July 1994). "Kava dermopathy". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 31 (1): 89–97. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(94)70142-3. PMID 8021378.

- "Kava Side Effects". The Kava Library. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- Jappe, Uta; Franke, Ingolf; Reinhold, Dirk; Gollnick, Harald P.M. (1998). "Sebotropic drug reaction resulting from kava-kava extract therapy: A new entity?". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 38 (1): 104–6. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(98)70547-X. PMID 9448214.

- Wheatley, David (1 June 2001). "Stress-induced insomnia treated with kava and valerian: singly and in combination". Human Psychopharmacology. 16 (4): 353–356. doi:10.1002/hup.299. ISSN 1099-1077. PMID 12404572. S2CID 37457833.

- Sarris, Jerome; Stough, Con; Bousman, Chad; Wahid, Zahra; Murray, Greg; Teschke, Rolf; Dowell, Ashley; Ng, Chee; Schweitzer, Isaac (1 October 2013). "Kava in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 33 (5): 643–48. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e318291be67. PMID 23635869. S2CID 13747661.

- Showman, Angelique F.; Baker, Jonathan D.; Linares, Christina; Naeole, Chrystie K.; Borris, Robert; Johnston, Edward; Konanui, Jerry; Turner, Helen (1 January 2015). "Contemporary Pacific and Western perspectives on 'awa (Piper methysticum) toxicology". Fitoterapia. 100: 56–67. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2014.11.012. ISSN 1873-6971. PMID 25464054.

- "Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code - Standard 2.6.3 - Kava". Federal Register of Legislation. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- "Travelers from Fiji to Australia can now take more kava for social functions". Xinhua. 17 December 2019. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Import requirements: Kava". The Office of Drug Control, Department of Health, Government of Australia. 1 December 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2022..

- "Kava fact sheet". Therapeutic Goods Administration, Government of Australia. April 2005. Archived from the original on 20 July 2006. Retrieved 10 July 2006. (Download PDF 44KB Archived 20 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine).

- "Kava". Northern Territory Government. 12 December 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- Armbruster, Stefan (10 July 2015). "Islanders shocked as Australia moves to ban kava". Special Broadcasting Service (SBS), Sydney. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- "Kava legal in WA, marketed at troubled sleepers". The West Australian. 13 February 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- C.I.J.M. Ross-van Dorp (2003). "Besluit van 23 april 2003, houdende wijziging van het Warenwetbesluit Kruidenpreparaten (verbod op Kava kava in kruidenpreparaten)" (PDF). Sdu Uitgevers. Staatsblad van het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 7 February 2007.

- "Fiji takes kava ban fight to WTO". The World Trade Review. August 2005. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- Bowman, Chakriya. "The Pacific Island Nations: Towards Shared Representation". WTO. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- "Comeback unter strengen Auflagen" (in German). Pharmazeutische Zeitung. 16 August 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- Joshua, Jane (17 February 2016). "New Kava Challenge". Vanuatu Daily Post. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- "The Medicines for Human Use (Kava-kava) (Prohibition) Order 2002". Legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- Garae, Len (27 December 2017). "Kava banned in Poland". Vanuatu Daily Post. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- "Rozporządzenie Ministra Zdrowia z dnia 17 sierpnia 2018 r. w sprawie wykazu substancji psychotropowych, środków odurzających oraz nowych substancji psychoaktywnych". prawo.sejm.gov.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- "Kava zalegalizowana. Marihuana będzie następna?". www.rp.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- Koninkrijksrelaties, Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en. "Warenwetbesluit Kruidenpreparaten". wetten.overheid.nl.

- "Dunne: Kava unaffected by Psychoactive Substances Bill". The Beehive. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- "Standard 2.6.3 – Kava – Food Standards (Proposal P1025 – Code Revision) Variation—Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code – Amendment No. 154 - 2015-gs1906 - New Zealand Gazette". gazette.govt.nz. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- "Marketed Health Products Directorate Heath Products and Foods Branch". Canadian Adverse Reaction Newsletter. 12 (4). 2002.

- "Listing of Drugs Currently Regulated as New Drugs (The New Drugs List)". www.hc-sc.gc.ca. Health Canada. 26 May 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- "Kava". HealthLink BC, Government of British Columbia. 23 September 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- "Ingredients - Kava". Health Canada. 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- "Consumer Advisory: Kava-Containing Dietary Supplements May be Associated With Severe Liver Injury". US Food and Drug Administration. 25 March 2002. Archived from the original on 3 June 2009. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- "Vanuatu - Legislation - Kava Act 2002". faolex.fao.org. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

External links

- "UNODC - Bulletin on Narcotics: The narcotic pepper - The chemistry and pharmacology of Piper methysticum and related species". United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 1973. pp. Issue 2. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- Kava ban documents

- Piper methysticum information from the Hawaiian Ecosystems at Risk project (HEAR)

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (9th ed.). 1882.