Hepatic encephalopathy

| Hepatic encephalopathy | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Portosystemic encephalopathy, hepatic coma,[1] coma hepaticum | |

| |

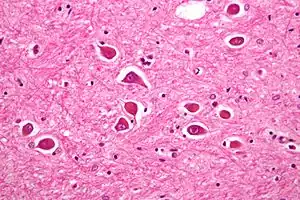

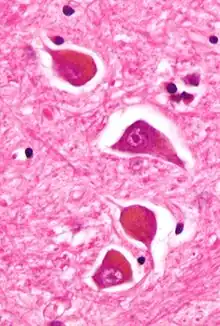

| Micrograph of Alzheimer type II astrocytes, as may be seen in hepatic encephalopathy. | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

| Symptoms | Altered level of consciousness, mood changes, personality changes, movement problems[2] |

| Types | Acute, recurrent, persistent[3] |

| Causes | Liver failure[2] |

| Risk factors | Infections, GI bleeding, constipation, electrolyte problems, certain medications[4] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms after ruling out other possible causes[2][5] |

| Differential diagnosis | Wernicke–Korsakoff’s syndrome, delirium tremens, hypoglycemia, subdural hematoma, hyponatremia[1] |

| Treatment | Supportive care, treating triggers, lactulose, liver transplant[1][3] |

| Prognosis | Average life expectancy less than a year in those with severe disease[1] |

| Frequency | Affects >40% with cirrhosis[6] |

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is an altered level of consciousness as a result of liver failure.[2] Its onset may be gradual or sudden.[2] Other symptoms may include movement problems, changes in mood, or changes in personality.[2] In the advanced stages it can result in a coma.[3]

Hepatic encephalopathy can occur in those with acute or chronic liver disease.[3] Episodes can be triggered by infections, GI bleeding, constipation, electrolyte problems, or certain medications.[4] The underlying mechanism is believed to involve the buildup of ammonia in the blood, a substance that is normally removed by the liver.[2] The diagnosis is typically based on symptoms after ruling out other potential causes.[2][5] It may be supported by blood ammonia levels, an electroencephalogram, or a CT scan of the brain.[3][5]

Hepatic encephalopathy is possibly reversible with treatment.[1] This typically involves supportive care and addressing the triggers of the event.[3] Lactulose or polyethylene glycol are frequently used to decrease ammonia levels.[1][7] Certain antibiotics (such as rifaximin) and probiotics are other potential options.[1] A liver transplant may improve outcomes in those with severe disease.[1]

More than 40% of people with cirrhosis develop hepatic encephalopathy.[6] More than half of those with cirrhosis and significant HE live less than a year.[1] In those who are able to get a liver transplant, the risk of death is less than 30% over the subsequent five years.[1] The condition has been described since at least 1860.[1]

Signs and symptoms

The mildest form of hepatic encephalopathy is difficult to detect clinically, but may be demonstrated on neuropsychological testing. It is experienced as forgetfulness, mild confusion, and irritability. The first stage of hepatic encephalopathy is characterised by an inverted sleep-wake pattern (sleeping by day, being awake at night). The second stage is marked by lethargy and personality changes. The third stage is marked by worsened confusion. The fourth stage is marked by a progression to coma.[3]

More severe forms of hepatic encephalopathy lead to a worsening level of consciousness, from lethargy to somnolence and eventually coma. In the intermediate stages, a characteristic jerking movement of the limbs is observed (asterixis, "liver flap" due to its flapping character); this disappears as the somnolence worsens. There is disorientation and amnesia, and uninhibited behaviour may occur. In the third stage, neurological examination may reveal clonus and positive Babinski sign. Coma and seizures represent the most advanced stage; cerebral oedema (swelling of the brain tissue) leads to death.[3]

Encephalopathy often occurs together with other symptoms and signs of liver failure. These may include jaundice (yellow discolouration of the skin and the whites of the eyes), ascites (fluid accumulation in the abdominal cavity), and peripheral oedema (swelling of the legs due to fluid build-up in the skin). The tendon reflexes may be exaggerated, and the plantar reflex may be abnormal, namely extending rather than flexing (Babinski's sign) in severe encephalopathy. A particular smell on an affected person's breath (foetor hepaticus) may be detected.[8]

Causes

In a small proportion of cases, the encephalopathy is caused directly by liver failure; this is more likely in acute liver failure. More commonly, especially in chronic liver disease, hepatic encephalopathy is triggered by an additional cause, and identifying these triggers can be important to treat the episode effectively.[3]

| Type | Causes[3][8][9] |

|---|---|

| Excessive nitrogen load |

Consumption of large amounts of protein, gastrointestinal bleeding e.g. from esophageal varices (blood is high in protein, which is reabsorbed from the bowel), kidney failure (inability to excrete nitrogen-containing waste products such as urea), constipation |

| Electrolyte or metabolic disturbance |

Hyponatraemia (low sodium level in the blood) and hypokalaemia (low potassium levels)—these are both common in those taking diuretics, often used for the treatment of ascites; furthermore alkalosis (decreased acid level), hypoxia (insufficient oxygen levels), dehydration |

| Drugs and medications |

Sedatives such as benzodiazepines (often used to suppress alcohol withdrawal or anxiety disorder), narcotics (used as painkillers or drugs of abuse), antipsychotics, alcohol intoxication |

| Infection | Pneumonia, urinary tract infection, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, other infections |

| Others | Surgery, progression of the liver disease, additional cause for liver damage (e.g. alcoholic hepatitis, hepatitis A) |

| Unknown | In 20–30% of cases, no clear cause for an attack can be found |

Hepatic encephalopathy may also occur after the creation of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). This is used in the treatment of refractory ascites, bleeding from oesophageal varices and hepatorenal syndrome.[10][11] TIPS-related encephalopathy occurs in about 30% of cases, with the risk being higher in those with previous episodes of encephalopathy, higher age, female sex, and liver disease due to causes other than alcohol.[9]

Pathogenesis

There are various explanations why liver dysfunction or portosystemic shunting might lead to encephalopathy. In healthy subjects, nitrogen-containing compounds from the intestine, generated by gut bacteria from food, are transported by the portal vein to the liver, where 80–90% are metabolised through the urea cycle and/or excreted immediately. This process is impaired in all subtypes of hepatic encephalopathy, either because the hepatocytes (liver cells) are incapable of metabolising the waste products or because portal venous blood bypasses the liver through collateral circulation or a medically constructed shunt. Nitrogenous waste products accumulate in the systemic circulation (hence the older term "portosystemic encephalopathy"). The most important waste product is ammonia (NH3). This small molecule crosses the blood–brain barrier and is absorbed and metabolised by the astrocytes, a population of cells in the brain that constitutes 30% of the cerebral cortex. Astrocytes use ammonia when synthesising glutamine from glutamate. The increased levels of glutamine lead to an increase in osmotic pressure in the astrocytes, which become swollen. There is increased activity of the inhibitory γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) system, and the energy supply to other brain cells is decreased. This can be thought of as an example of brain edema of the "cytotoxic" type.[12]

Despite numerous studies demonstrating the central role of ammonia, ammonia levels do not always correlate with the severity of the encephalopathy; it is suspected that this means that more ammonia has already been absorbed into the brain in those with severe symptoms whose serum levels are relatively low.[3][8] Other waste products implicated in hepatic encephalopathy include mercaptans (substances containing a thiol group), short-chain fatty acids, and phenol.[8]

Numerous other abnormalities have been described in hepatic encephalopathy, although their relative contribution to the disease state is uncertain. Loss of glutamate transporter gene expression (especially EAAT 2) has been attributed to acute liver failure.[13] Benzodiazepine-like compounds have been detected at increased levels as well as abnormalities in the GABA neurotransmission system. An imbalance between aromatic amino acids (phenylalanine, tryptophan and tyrosine) and branched-chain amino acids (leucine, isoleucine and valine) has been described; this would lead to the generation of false neurotransmitters (such octopamine and 2-hydroxyphenethylamine). Dysregulation of the serotonin system, too, has been reported. Depletion of zinc and accumulation of manganese may play a role.[3][8] Inflammation elsewhere in the body may precipitate encephalopathy through the action of cytokines and bacterial lipopolysaccharide on astrocytes.[9]

Diagnosis

Investigations

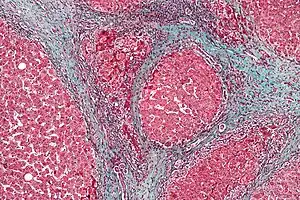

The diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy can only be made in the presence of confirmed liver disease (types A and C) or a portosystemic shunt (type B), as its symptoms are similar to those encountered in other encephalopathies. To make the distinction, abnormal liver function tests and/or ultrasound suggesting liver disease are required, and ideally a liver biopsy.[3][8] The symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy may also arise from other conditions, such as bleeding in the brain and seizures (both of which are more common in chronic liver disease). A CT scan of the brain may be required to exclude bleeding in the brain, and if seizure activity is suspected an electroencephalograph (EEG) study may be performed.[3] Rarer mimics of encephalopathy are meningitis, encephalitis, Wernicke's encephalopathy and Wilson's disease; these may be suspected on clinical grounds and confirmed with investigations.[8][14]

The diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy is a clinical one, once other causes for confusion or coma have been excluded; no test fully diagnoses or excludes it. Serum ammonia levels are elevated in 90% of people, but not all hyperammonaemia (high ammonia levels in the blood) is associated with encephalopathy.[3][8] A CT scan of the brain usually shows no abnormality except in stage IV encephalopathy, when brain swelling (cerebral oedema) may be visible.[8] Other neuroimaging modalities, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are not currently regarded as useful, although they may show abnormalities.[14] Electroencephalography shows no clear abnormalities in stage 0, even if minimal HE is present; in stages I, II and III there are triphasic waves over the frontal lobes that oscillate at 5 Hz, and in stage IV there is slow delta wave activity.[3] However, the changes in EEG are not typical enough to be useful in distinguishing hepatic encephalopathy from other conditions.[14]

Once the diagnosis of encephalopathy has been made, efforts are made to exclude underlying causes (such as listed above in "causes"). This requires blood tests (urea and electrolytes, full blood count, liver function tests), usually a chest X-ray, and urinalysis. If there is ascites, a diagnostic paracentesis (removal of a fluid sample with a needle) may be required to identify spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP).[3]

.jpg.webp) Acute severe hepatic encephalopathy

Acute severe hepatic encephalopathy.jpg.webp) Acute severe hepatic encephalopathy

Acute severe hepatic encephalopathy.jpg.webp) Acute severe hepatic encephalopathy

Acute severe hepatic encephalopathy

Classification

West Haven criteria

The severity of hepatic encephalopathy is graded with the West Haven Criteria; this is based on the level of impairment of autonomy, changes in consciousness, intellectual function, behavior, and the dependence on therapy.[3][14]

- Grade 0 - No obvious changes other than potentially mild decrease in intellectual ability and coordination

- Grade 1 - Trivial lack of awareness; euphoria or anxiety; shortened attention span; impaired performance of addition or subtraction

- Grade 2 - Lethargy or apathy; minimal disorientation for time or place; subtle personality change; inappropriate behaviour

- Grade 3 - Somnolence to semistupor, but responsive to verbal stimuli; confusion; gross disorientation

- Grade 4 - Coma

Types

A classification of hepatic encephalopathy was introduced at the World Congress of Gastroenterology 1998 in Vienna. According to this classification, hepatic encephalopathy is subdivided in type A, B and C depending on the underlying cause.[14]

- Type A (=acute) describes hepatic encephalopathy associated with acute liver failure, typically associated with cerebral oedema

- Type B (=bypass) is caused by portal-systemic shunting without associated intrinsic liver disease

- Type C (=cirrhosis) occurs in people with cirrhosis - this type is subdivided in episodic, persistent and minimal encephalopathy

The term minimal encephalopathy (MHE) is defined as encephalopathy that does not lead to clinically overt cognitive dysfunction, but can be demonstrated with neuropsychological studies.[14][15] This is still an important finding, as minimal encephalopathy has been demonstrated to impair quality of life and increase the risk of involvement in road traffic accidents.[16]

Minimal HE

The diagnosis of minimal hepatic encephalopathy requires neuropsychological testing by definition. Older tests include the "numbers connecting test" A and B (measuring the speed at which one could connect randomly dispersed numbers 1–20), the "block design test" and the "digit-symbol test".[14] In 2009 an expert panel concluded that neuropsychological test batteries aimed at measuring multiple domains of cognitive function are generally more reliable than single tests, and tend to be more strongly correlated with functional status. Both the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS)[17] and PSE-Syndrom-Test[18] may be used for this purpose.[15] The PSE-Syndrom-Test, developed in Germany and validated in several other European countries, incorporates older assessment tools such as the number connection test.[14][15][16][18]

Treatment

Those with severe encephalopathy (stages 3 and 4) are at risk of obstructing their airway due to decreased protective reflexes such as the gag reflex. This can lead to respiratory arrest. Transferring the person to a higher level of nursing care, such as an intensive care unit, is required and intubation of the airway is often necessary to prevent life-threatening complications (e.g., aspiration or respiratory failure).[8][19] Placement of a nasogastric tube permits the safe administration of nutrients and medication.[3]

The treatment of hepatic encephalopathy depends on the suspected underlying cause (types A, B or C) and the presence or absence of underlying causes. If encephalopathy develops in acute liver failure (type A), even in a mild form (grade 1–2), it indicates that a liver transplant may be required, and transfer to a specialist centre is advised.[19] Hepatic encephalopathy type B may arise in those who have undergone a TIPS procedure; in most cases this resolves spontaneously or with the medical treatments discussed below, but in a small proportion of about 5%, occlusion of the shunt is required to address the symptoms.[9]

In hepatic encephalopathy type C, the identification and treatment of alternative or underlying causes is central to the initial management.[3][8][9][16] Given the frequency of infection as the underlying cause, antibiotics are often administered empirically (without knowledge of the exact source and nature of the infection).[3][9] Once an episode of encephalopathy has been effectively treated, a decision may need to be made on whether to prepare for a liver transplant.[16]

Diet

In the past, it was thought that consumption of protein even at normal levels increased the risk of hepatic encephalopathy. This has been shown to be incorrect. Furthermore, many people with chronic liver disease are malnourished and require adequate protein to maintain a stable body weight. A diet with adequate protein and energy is therefore recommended.[3][9]

Dietary supplementation with branched-chain amino acids has shown improvement of encephalopathy and other complications of cirrhosis.[3][9] Some studies have shown benefit of administration of probiotics ("healthy bacteria").[9]

Laxatives

Lactulose and lactitol are disaccharides that are not absorbed from the digestive tract. They are thought to decrease the generation of ammonia by bacteria, render the ammonia inabsorbable by converting it to ammonium (NH4+) ions, and increase transit of bowel content through the gut. Doses of 15-30 ml are typically administered three times a day; the result is aimed to be 3–5 soft stools a day, or (in some settings) a stool pH of <6.0.[3][8][9][16] Lactulose may also be given by enema, especially if encephalopathy is severe.[16] More commonly, phosphate enemas are used. This may relieve constipation, one of the causes of encephalopathy, and increase bowel transit.[3]

Lactulose and lactitol are beneficial for treating hepatic encephalopathy, and are the recommended first-line treatment.[3][20] Lactulose does not appear to be more effective than lactitol for treating people with hepatic encephalopathy.[20] Side effects of lactulose and lactitol include the possibility of diarrhea, abdominal bloating, gassiness, and nausea.[20] In acute liver failure, it is unclear whether lactulose is beneficial. The possible side effect of bloating may interfere with a liver transplant procedure if required.[19]

Polyethylene glycol appears to be more effective than lactulose.[7]

Antibiotics

The antibiotic rifaximin may be recommended in addition to lactulose for those with recurrent disease.[1] It is a nonabsorbable antibiotic from the rifamycin class. This is thought to work in a similar way to other antibiotics, but without the complications attached to neomycin or metronidazole. Due to the long history and lower cost of lactulose use, rifaximin is generally only used as a second-line treatment if lactulose is poorly tolerated or not effective. When rifaximin is added to lactulose, the combination of the two may be more effective than each component separately.[3] Rifaximin is more expensive than lactulose, but the cost may be offset by fewer hospital admissions for encephalopathy.[16]

The antibiotics neomycin and metronidazole are other antibiotics used to treat hepatic encephalopathy.[21] The rationale of their use was the fact that ammonia and other waste products are generated and converted by intestinal bacteria, and killing these bacteria would reduce the generation of these waste products. Neomycin was chosen because of its low intestinal absorption, as neomycin and similar aminoglycoside antibiotics may cause hearing loss and kidney failure if used by injection. Later studies showed that neomycin was indeed absorbed when taken by mouth, with resultant complications. Metronidazole, similarly, is less commonly used because prolonged use can cause nerve damage, in addition to gastrointestinal side effects.[3]

Other

The combination of L-ornithine and L-aspartate (LOLA) may lowers the level of ammonia in a person's blood.[22] Very weak evidence from indicates that LOLA treatment may benefit people with hepatic encephalopathy.[22] LOLA may be combined with lactulose or rifaximin if these alone are ineffective at controlling symptoms.[3]

Prognosis

Once hepatic encephalopathy has developed, the prognosis is determined largely by other markers of liver failure, such as the levels of albumin (a protein produced by the liver), the prothrombin time (a test of coagulation, which relies on proteins produced in the liver), the presence of ascites and the level of bilirubin (a breakdown product of hemoglobin which is conjugated and excreted by the liver). Together with the severity of encephalopathy, these markers have been incorporated into the Child-Pugh score; this score determines the one- and two-year survival and may assist in a decision to offer liver transplantation.[14]

In acute liver failure, the development of severe encephalopathy strongly predicts short-term mortality, and is almost as important as the nature of the underlying cause of the liver failure in determining the prognosis. Historically, widely used criteria for offering liver transplantation, such as King's College Criteria, are of limited use and recent guidelines discourage excessive reliance on these criteria. The occurrence of hepatic encephalopathy in people with Wilson's disease (hereditary copper accumulation) and mushroom poisoning indicates an urgent need for a liver transplant.[19]

Epidemiology

In those with cirrhosis, the risk of developing hepatic encephalopathy is 20% per year, and at any time about 30–45% of people with cirrhosis exhibit evidence of overt encephalopathy. The prevalence of minimal hepatic encephalopathy detectable on formal neuropsychological testing is 60–80%; this increases the likelihood of developing overt encephalopathy in the future.[16]

History

The occurrence of disturbed behaviour in people with jaundice may have been described in antiquity by Hippocrates of Cos (ca. 460–370 BCE).[18][23] Celsus and Galen (first and third century respectively) both recognised the condition. Many modern descriptions of the link between liver disease and neuropsychiatric symptoms were made in the eighteenth and nineteenth century; for instance, Giovanni Battista Morgagni (1682–1771) reported in 1761 that it was a progressive condition.[23]

In the 1950s, several reports enumerated the numerous abnormalities reported previously, and confirmed the previously enunciated theory that metabolic impairment and portosystemic shunting are the underlying mechanisms behind hepatic encephalopathy, and that the nitrogen-rich compounds originate from the intestine.[18][24] Professor Dame Sheila Sherlock (1918–2001) performed many of these studies at the Royal Postgraduate Medical School in London and subsequently at the Royal Free Hospital. The same group investigated protein restriction[23] and neomycin.[25]

The West Haven classification was formulated by Professor Harold Conn (1925–2011) and colleagues at Yale University while investigating the therapeutic efficacy of lactulose.[14][26][27]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Wijdicks, EF (27 October 2016). "Hepatic Encephalopathy". The New England Journal of Medicine. 375 (17): 1660–1670. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1600561. PMID 27783916.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Hepatic encephalopathy". GARD. 2016. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Cash WJ, McConville P, McDermott E, McCormick PA, Callender ME, McDougall NI (January 2010). "Current concepts in the assessment and treatment of hepatic encephalopathy". QJM. 103 (1): 9–16. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcp152. PMID 19903725.

- 1 2 Starr, SP; Raines, D (15 December 2011). "Cirrhosis: diagnosis, management, and prevention". American Family Physician. 84 (12): 1353–9. PMID 22230269.

- 1 2 3 "Portosystemic Encephalopathy - Hepatic and Biliary Disorders". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Archived from the original on 22 April 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- 1 2 Ferri, Fred F. (2017). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2018 E-Book: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 577. ISBN 9780323529570. Archived from the original on 2017-07-30.

- 1 2 Hoilat, GJ; Ayas, MF; Hoilat, JN; Abu-Zaid, A; Durer, C; Durer, S; Adhami, T; John, S (May 2021). "Polyethylene glycol versus lactulose in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ open gastroenterology. 8 (1). doi:10.1136/bmjgast-2021-000648. PMID 34006606.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Chung RT, Podolsky DK (2005). "Cirrhosis and its complications". In Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, et al. (eds.). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (16th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. pp. 1858–69. ISBN 978-0-07-139140-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Sundaram V, Shaikh OS (July 2009). "Hepatic encephalopathy: pathophysiology and emerging therapies". Med. Clin. North Am. 93 (4): 819–36, vii. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2009.03.009. PMID 19577116.

- ↑ Khan S, Tudur Smith C, Williamson P, Sutton R (2006). "Portosystemic shunts versus endoscopic therapy for variceal rebleeding in patients with cirrhosis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD000553. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000553.pub2. PMC 7045742. PMID 17054131.

- ↑ Saab S, Nieto JM, Lewis SK, Runyon BA (2006). "TIPS versus paracentesis for cirrhotic patients with refractory ascites". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD004889. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004889.pub2. PMID 17054221.

- ↑ Ryan JM, Shawcross DL (2011). "Hepatic encephalopathy". Medicine. 39 (10): 617–620. doi:10.1016/j.mpmed.2011.07.008.

- ↑ Thumburu, KK; Dhiman, RK; Vasishta, RK; Chakraborti, A; Butterworth, RF; Beauchesne, E; Desjardins, P; Goyal, S; Sharma, N; Duseja, A; Chawla, Y (Mar 2014). "Expression of astrocytic genes coding for proteins implicated in neural excitation and brain edema is altered after acute liver failure". Journal of Neurochemistry. 128 (5): 617–27. doi:10.1111/jnc.12511. PMID 24164438.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Ferenci P, Lockwood A, Mullen K, Tarter R, Weissenborn K, Blei A (2002). "Hepatic encephalopathy--definition, nomenclature, diagnosis, and quantification: final report of the working party at the 11th World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna, 1998". Hepatology. 35 (3): 716–21. doi:10.1053/jhep.2002.31250. PMID 11870389.

- 1 2 3 Randolph C, Hilsabeck R, Kato A, et al. (May 2009). "Neuropsychological assessment of hepatic encephalopathy: ISHEN practice guidelines". Liver Int. 29 (5): 629–35. doi:10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02009.x. PMID 19302444. Archived from the original on 2012-12-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bajaj JS (March 2010). "Review article: the modern management of hepatic encephalopathy". Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 31 (5): 537–47. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04211.x. PMID 20002027.

- ↑ Randolph C, Tierney MC, Mohr E, Chase TN (June 1998). "The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): preliminary clinical validity". J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 20 (3): 310–9. doi:10.1076/jcen.20.3.310.823. PMID 9845158.

- 1 2 3 4 Weissenborn K, Ennen JC, Schomerus H, Rückert N, Hecker H (May 2001). "Neuropsychological characterization of hepatic encephalopathy". J. Hepatol. 34 (5): 768–73. doi:10.1016/S0168-8278(01)00026-5. PMID 11434627.

- 1 2 3 4 Polson J, Lee WM (May 2005). "AASLD position paper: the management of acute liver failure". Hepatology. 41 (5): 1179–97. doi:10.1002/hep.20703. PMID 15841455. Archived from the original on 2012-12-16.

- 1 2 3 Gluud, Lise Lotte; Vilstrup, Hendrik; Morgan, Marsha Y. (2016-05-06). "Non-absorbable disaccharides versus placebo/no intervention and lactulose versus lactitol for the prevention and treatment of hepatic encephalopathy in people with cirrhosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD003044. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003044.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7004252. PMID 27153247.

- ↑ Ferenci, P (May 2017). "Hepatic encephalopathy". Gastroenterology Report. 5 (2): 138–147. doi:10.1093/gastro/gox013. PMC 5421503. PMID 28533911.

- 1 2 Goh, Ee Teng; Stokes, Caroline S.; Sidhu, Sandeep S.; Vilstrup, Hendrik; Gluud, Lise Lotte; Morgan, Marsha Y. (2018-05-15). "L-ornithine L-aspartate for prevention and treatment of hepatic encephalopathy in people with cirrhosis" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5: CD012410. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012410.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6494563. PMID 29762873. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-04-30. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- 1 2 3 Summerskill WH, Davidson EA, Sherlock S, Steiner RE (April 1956). "The neuropsychiatric syndrome associated with hepatic cirrhosis and an extensive portal collateral circulation". Q. J. Med. 25 (98): 245–66. PMID 13323252.

- ↑ Sherlock S, Summerskill WH, White LP, Phear EA (September 1954). "Portal-systemic encephalopathy; neurological complications of liver disease". Lancet. 264 (6836): 453–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(54)91874-7. PMID 13193045.

- ↑ Last PM, Sherlock S (February 1960). "Systemic absorption of orally administered neomycin in liver disease". N. Engl. J. Med. 262 (8): 385–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM196002252620803. PMID 14414396.

- ↑ Conn HO, Leevy CM, Vlahcevic ZR, et al. (1977). "Comparison of lactulose and neomycin in the treatment of chronic portal-systemic encephalopathy. A double blind controlled trial". Gastroenterology. 72 (4 Pt 1): 573–83. doi:10.1016/S0016-5085(77)80135-2. PMID 14049. Archived from the original on 2013-04-14.

- ↑ Boyer JL, Garcia-Tsao G, Groszmann RJ (February 2012). "In Memoriam: Harold O. Conn, M.D.". Hepatology. 55 (2): 658–9. doi:10.1002/hep.25550.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |