Metamizole

Metamizole, or dipyrone, is a painkiller, spasm reliever, and fever reliever that also has anti-inflammatory effects. It is most commonly given by mouth or by intravenous infusion.[4][5]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Novalgin, Algocalmin, [1] others[2] |

| Other names | Dipyrone (BAN UK, USAN US) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, IM, IV, rectal |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 100% (active metabolites)[5] |

| Protein binding | 48–58% (active metabolites)[5] |

| Metabolism | Liver[5] |

| Elimination half-life | 14 minutes (parent compound; parenteral);[4] metabolites: 2–4 hours[5] |

| Excretion | Urine (96%, IV; 85%, oral), faeces (4%, IV).[4] |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.631 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

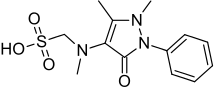

| Formula | C13H17N3O4S |

| Molar mass | 311.36 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

Although it is available over-the-counter in some countries, it is banned in others, due to its potential for adverse events, including agranulocytosis.[6][7] A study by one of the manufacturers of the drug found the risk of agranulocytosis within the first week of treatment to be a mere 1.1 in a million, versus 5.92 in a million for diclofenac.[8] It is in the ampyrone sulfonate family of medicines.

It was patented in 1922[9] and was first used medically in Germany under the brandname "Novalgin". For many years, it was available over-the-counter in most countries, before its withdrawal due to severe adverse effects.[10] Metamizole is marketed under various trade names.[2][3]

Medical uses

It is primarily used for perioperative pain, acute injury, colic, cancer pain, other acute/chronic forms of pain and high fever unresponsive to other agents.[4]

Special populations

Its use in pregnancy is advised against, although animal studies are reassuring in that they show minimal risk of birth defects. Its use in the elderly and those with liver or kidney impairment is advised against, but if these groups of people must be treated, a lower dose and caution is usually advised. Its use during lactation is advised against, as it is excreted in breast milk.[4]

Adverse effects

Metamizole has a potential of blood-related toxicity (blood dyscrasias), but causes less kidney, cardiovascular, and gastrointestinal toxicity than non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).[5] Like NSAIDs, it can trigger bronchospasm or anaphylaxis, especially in those with asthma.[7]

Serious side effects include agranulocytosis, aplastic anaemia, hypersensitivity reactions (like anaphylaxis and bronchospasm), toxic epidermal necrolysis and it may provoke acute attacks of porphyria, as it is chemically related to the sulfonamides.[3][5][7] The relative risk for agranulocytosis appears to greatly vary according to the country of estimates on said rate and opinion on the risk is strongly divided.[3][11] Genetics may play a significant role in metamizole sensitivity.[12] It is suggested that some populations are more prone to suffer from metamizole induced agranulocytosis than others. As an example, metamizole-related agranulocytosis seems to be an adverse effect more frequent in British population as opposed to Spaniards.[13]

According to a systematic review from 2016 Metamizole significantly increased the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding by a factor ranging from 1.4 to 2.7 (relative risk).[14]

Contraindications

Previous hypersensitivity (such as agranulocytosis or anaphylaxis) to metamizole or any of the excipients (e.g. lactose) in the preparation used, acute porphyria, impaired haematopoiesis (such as due to treatment with chemotherapy agents), third trimester of pregnancy (potential for adverse effects in the newborn), lactation, children with a body weight below 16 kg, history of aspirin-induced asthma and other hypersensitivity reactions to analgesics.[4]

| Drug(s) | Interaction/reason for theoretical potential for interaction |

|---|---|

| Ciclosporin | Decreased serum levels of ciclosporin. |

| Chlorpromazine | Additive hypothermia (low body temperature) may result. |

| Methotrexate | Additive risk for haematologic (blood) toxicity. |

Oral anticoagulants (blood thinners), lithium, captopril, triamterene and antihypertensives may also interact with metamizole, as other pyrazolones are known to interact adversely with these substances.

Overdose

It is considered fairly safe on overdose, but in these cases supportive measures are usually advised as well as measures to limit absorption (such as activated charcoal) and accelerate excretion (such as haemodialysis).[4]

Physicochemistry

It is a sulfonic acid and comes in calcium, sodium and magnesium salt forms.[3] Its sodium salt monohydrate form is a white/almost crystalline powder that is unstable in the presence of light, highly soluble in water and ethanol but practically insoluble in dichloromethane.[15]

Pharmacology

Its precise mechanism of action is unknown, although it is believed that inhibiting brain and spinal cord prostaglandin (fat-like molecules that are involved in inflammation, pain and fever) synthesis might be involved.[7] Recently, researchers uncovered another mechanism involving metamizole being a prodrug. In this proposal, not yet verified by other researchers, the metamizole itself breaks down into other chemicals that are the actual active agents. The result is a pair of cannabinoid and NSAID arachidonic acid conjugates (although not in the strict chemical meaning of the word) of metamizole's breakdown products.[16] Despite this, studies in animals have found that the CB1 cannabinoid receptor is not involved in the analgesia induced by metamizole.[17] Although it seems to inhibit fevers caused by prostaglandins, especially prostaglandin E2,[18] metamizole appears to produce its therapeutic effects by means of its metabolites, especially N-methyl-4-aminoantipyrine (MAA) and 4-Aminoantipyrine (AA).[4]

| Metabolite | Acronym | Biologically active? | Pharmacokinetic properties |

|---|---|---|---|

N-methyl-4-aminoantipyrine | MAA | Yes | Bioavailability≈90%. Plasma protein binding: 58%. Excreted in the urine as 3±1% of the initial (oral) dose |

4-aminoantipyrine | AA | Yes | Bioavailability≈22.5%. Plasma protein binding: 48%. Excreted in the urine as 6±3% of the initial (oral) dose |

N-formyl-4-aminoantipyrine | FAA | No | Plasma protein binding: 18%. Excretion in the urine as 23±4% of the initial oral dose |

N-acetyl-4-aminoantipyrine | AAA | No | Plasma protein binding: 14%. Excretion in the urine as 26±8% of the initial oral dose |

History

Ludwig Knorr was a student of Emil Fischer who won the Nobel Prize for his work on purines and sugars, which included the discovery of phenylhydrazine.[1][19] In the 1880s, Knorr was trying to make quinine derivatives from phenylhydrazine, and instead made a pyrazole derivative, which after a methylation, he made into phenazone, also called antipyrine, which has been called "the 'mother' of all modern antipyretic analgesics."[1][20]: 26–27 Sales of that drug exploded, and in the 1890s chemists at Teerfarbenfabrik Meister, Lucius & Co. (a precursor of Hoechst AG which is now Sanofi), made another derivative called pyramidon which was three times more active than antipyrine.[1]

In 1893, a derivative of antipyrine, aminopyrine, was made by Friedrich Stolz at Hoechst.[20]: 26–27 Yet later, chemists at Hoechst made a derivative, melubrine (sodium antipyrine aminomethanesulfonate), which was introduced in 1913;[21] finally in 1920, metamizole was synthesized.[8] Metamizole is a methyl derivative of melubrine and is also a more soluble prodrug of pyramidon.[1][20]: 26–27 Metamizole was first marketed in Germany as "Novalgin" in 1922.[1][8]

Society and culture

Legal status

_Availability_World_Map.svg.png.webp)

World map of availability of Metamizole (Dipyrone)

Over-the-counter with limited restrictions.

Available, but no data on the requirement of prescriptions.

Prescription-only, with fairly limited restrictions on its use.

Prescription-only, with extensive restrictions on its use.

Banned for human use. It may still be used by veterinary cases.

No data.

|

Metamizole is banned in several countries, available by prescription in others (sometimes with strong warnings, sometimes without), and available over the counter in yet others.[10][22][23] For example, approval was withdrawn in Sweden (1974), the USA (1977), and India (2013, ban lifted in 2014).[24][25]

Although it's banned in USA, it was reported by small surveys that 28% of Hispanics in Miami have possession of it,[26] and 38% of Hispanics in San Diego, CA reported some usage.[27]

Amid the opioid crisis, a study pointed the legal status of metamizole have a relation to the consumption of oxycodone, showing the use of those drugs were inversely correlated. Its use could be beneficial when adjusted for the addictive-risk of opioids, specially on limited and controlled use of metamizole.[28] A 2019 Israeli conference also justified the approved status as a preventive to opioid dependence, and metamizole being safer than most analgesics for renal impaired patients.[29]

It's the most sold medication in São Paulo, Brazil, accounting for 488 tons in 2016.[30]

In 2012, headache accounts for 70% of its use in Indonesia.[31]

In 2018, investigators in Spain looked into Nolotil (as metamizole is known in Spain) after the death of several British people in Spain. A possible factor in these deaths might have been a side effect of metamizole that can cause agranulocytosis (a lowering of white blood cell count).[32]

Brand names

Metamizole is generic, and in countries where it is marketed, it is available under many brand names.[2] In Russia, it is commonly sold under the "Analgin" (Russian: Анальгин) trade name.[33][34]

In Romania it's available as the original marketed pharmaceutical product by Zentiva as Algocalmin, as 500 mg immediate release tablets. It's also available as an injection with 1 g of metamizole sodium dissolved in 2 ml of solvent.

In Israel it's sold under the brand name "Optalgin" (hebrew: אופטלגין), manufactured by Teva.

References

- Brune K (December 1997). "The early history of non-opioid analgesics". Acute Pain. 1: 33–40. doi:10.1016/S1366-0071(97)80033-2.

- Drugs.com Drugs.com international listings for Metamizole Page accessed June 21, 2015

- Brayfield A, ed. (13 December 2013). "Dipyrone". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- "Fachinformation (Zusammenfassung der Merkmale des Arzneimittels) Novaminsulfon injekt 1000 mg Lichtenstein Novaminsulfon injekt 2500 mg Lichtenstein" (PDF). Winthrop Arzneimittel GmbH (in German). Zinteva Pharm GmbH. February 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- Jage J, Laufenberg-Feldmann R, Heid F (April 2008). "[Drugs for postoperative analgesia: routine and new aspects. Part 1: non-opioids]" [Drugs for postoperative analgesia: routine and new aspects. Part 1: non-opioids]. Der Anaesthesist (in German). 57 (4): 382–390. doi:10.1007/s00101-008-1326-x. PMID 18351305. S2CID 32814418.

- Lutz M (November 2019). "Metamizole (Dipyrone) and the Liver: A Review of the Literature". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 59 (11): 1433–1442. doi:10.1002/jcph.1512. PMID 31433499.

- Brack A, Rittner HL, Schäfer M (March 2004). "Nichtopioidanalgetika zur perioperativen Schmerztherapie" [Non-opioid analgesics for perioperative pain therapy. Risks and rational basis for use]. Der Anaesthesist (in German). 53 (3): 263–280. doi:10.1007/s00101-003-0641-5. PMID 15021958. S2CID 8829564.

- Nikolova I, Tencheva J, Voinikov J, Petkova V, Benbasat N, Danchev N (2014). "Metamizole: A Review Profile of a Well-Known "Forgotten" Drug. Part I: Pharmaceutical and Nonclinical Profile". Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment. 26 (6): 3329–3337. doi:10.5504/BBEQ.2012.0089. ISSN 1310-2818. S2CID 56205439.

- Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 530. ISBN 9783527607495.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2005). Consolidated List of Products Whose Consumption and/or Sale Have Been Banned, Withdrawn, Severely Restricted of Not Approved by Governments (PDF) (12th ed.). New York: United Nations. pp. 171–5. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- Pogatzki-Zahn E, Chandrasena C, Schug SA (October 2014). "Nonopioid analgesics for postoperative pain management". Current Opinion in Anesthesiology. 27 (5): 513–519. doi:10.1097/ACO.0000000000000113. PMID 25102238. S2CID 31337982.

- García-Martín E, Esguevillas G, Blanca-López N, García-Menaya J, Blanca M, Amo G, et al. (September 2015). "Genetic determinants of metamizole metabolism modify the risk of developing anaphylaxis". Pharmacogenetics and Genomics. 25 (9): 462–464. doi:10.1097/FPC.0000000000000157. PMID 26111152.

- Mérida Rodrigo L, Faus Felipe V, Poveda Gómez F, García Alegría J (April 2009). "[Agranulocytosis from metamizole: a potential problem for the British population]". Revista Clinica Espanola. 209 (4): 176–179. doi:10.1016/s0014-2565(09)71310-4. PMID 19457324.

- Andrade S, Bartels DB, Lange R, Sandford L, Gurwitz J (October 2016). "Safety of metamizole: a systematic review of the literature". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 41 (5): 459–477. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12422. PMID 27422768. S2CID 24538147.

- Council of Europe; Council of Europe. European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & HealthCare (EDQM); Rada Europy; European Pharmacopoeia Commission; European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & Healthcare (2013). European Pharmacopoeia: Published in Accordance with the Convention on the Elaboration of a European Pharmacopoeia (European Treaty Series No. 50). Council of Europe. ISBN 978-92-871-7527-4.

- Jasiecka A, Maślanka T, Jaroszewski JJ (2014). "Pharmacological characteristics of metamizole". Polish Journal of Veterinary Sciences. 17 (1): 207–214. doi:10.2478/pjvs-2014-0030. PMID 24724493.

- Elmas P, Ulugol A (November 2013). "Involvement of cannabinoid CB1 receptors in the antinociceptive effect of dipyrone". Journal of Neural Transmission. 120 (11): 1533–1538. doi:10.1007/s00702-013-1052-7. PMID 23784345. S2CID 1487332.

- Malvar D, Aguiar FA, Vaz A, Assis DC, de Melo MC, Jabor VA, et al. (August 2014). "Dipyrone metabolite 4-MAA induces hypothermia and inhibits PGE2 -dependent and -independent fever while 4-AA only blocks PGE2 -dependent fever". British Journal of Pharmacology. 171 (15): 3666–3679. doi:10.1111/bph.12717. PMC 4128064. PMID 24712707.

- "Emil Fischer – Biographical". Nobel Committee.

- Raviña Rubira E (2011). The Evolution of Drug Discovery: From Traditional Medicines to Modern Drugs. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-32669-3.

- "New and Nonofficial Remedies: Melubrine". JAMA. 61 (11): 869. 1913.

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat Consolidated List of Products Whose Consumption and/or Sale Have Been Banned, Withdrawn, Severely Restricted or not Approved by Governments Fourteenth Issue (New data only) (January 2005 – October 2008): Pharmaceuticals United Nations – New York, 2009

- Rogosch T, Sinning C, Podlewski A, Watzer B, Schlosburg J, Lichtman AH, et al. (January 2012). "Novel bioactive metabolites of dipyrone (metamizol)". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 20 (1): 101–107. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2011.11.028. PMC 3248997. PMID 22172309.

- Bhaumik S (July 2013). "India's health ministry bans pioglitazone, metamizole, and flupentixol-melitracen". BMJ. 347: f4366. doi:10.1136/bmj.f4366. PMID 23833116. S2CID 45107003.

- "Govt lifts ban on painkiller Analgin". Business Standard India. 19 March 2014.

- Garcia S, Canoniero M, Lopes G, Soriano AO (September 2006). "Metamizole use among Hispanics in Miami: report of a survey conducted in a primary care setting". Southern Medical Journal. 99 (9): 924–926. doi:10.1097/01.smj.0000233020.68212.8f. PMID 17004525. S2CID 41638378.

- Taylor L, Abarca S, Henry B, Friedman L (September 2001). "Use of Neo-melubrina, a banned antipyretic drug, in San Diego, California: a survey of patients and providers". The Western Journal of Medicine. 175 (3): 159–163. doi:10.1136/ewjm.175.3.159. PMC 1071527. PMID 11527837.

- Preissner S, Siramshetty VB, Dunkel M, Steinborn P, Luft FC, Preissner R (2019). "Pain-Prescription Differences - An Analysis of 500,000 Discharge Summaries". Current Drug Research Reviews. 11 (1): 58–66. doi:10.2174/1874473711666180911091846. PMID 30207223. S2CID 52192130.

- Dinavitser N (January 2020). "Dipyrone – a Good Medication with a Bad Reputation" (PDF). Journal of Medical Toxicology. Rambam Health Care Campus, Haifa, Israel: American College of Medical Toxicology. 16 (1): 75–86. doi:10.1007/s13181-019-00743-w. PMC 6942089. PMID 31721040.

ACMT/IST 2019 American-Israeli Medical Toxicology Conference

- Aragão RB, Semensatto D, Calixto LA, Labuto G (2020). "Pharmaceutical market, environmental public policies and water quality: the case of the São Paulo Metropolitan Region, Brazil". Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 36 (11): e00192319. doi:10.1590/0102-311x00192319. ISSN 1678-4464. PMID 33237204. S2CID 227168554.

- Kurniawati M, Ikawati Z, Raharjo B (2012). "The evaluation of metamizole use in some places of pharmacy service in Cilacap county". Jurnal Manajemen Dan Pelayanan Farmasi (Journal of Management and Pharmacy Practice) (in Indonesian). 2 (1): 50–55. doi:10.22146/jmpf.60 (inactive 31 July 2022).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2022 (link) - "Exclusive: southern spain hospitals in british expat hotspot issue warning for 'lethal' painkiller nolotil". 23 April 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- "Анальгин Авексима - официальная инструкция по применению, аналоги". medi.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2019-01-08.

- "Анальгин". ozonpharm.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2019-01-08.