Ixazomib

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Ninlaro |

| Other names | Ixazomib citrate, MLN2238 |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Proteasome inhibitor[1] |

| Main uses | Multiple myeloma[1] |

| Side effects | Diarrhea, constipation, low platelets, low white blood cells, peripheral neuropathy, nausea, swelling[1] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth (capsules) |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a616008 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 58%[2] |

| Protein binding | 99% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (CYP: 3A4 (42%), 1A2 (26%), 2B6 (16%) and others) |

| Elimination half-life | 9.5 days |

| Excretion | Urine (62%), faeces (22%) |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C14H19BCl2N2O4 |

| Molar mass | 361.03 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Ixazomib, sold under the brand name Ninlaro, is a medication used to treat multiple myeloma.[1] It is used together with lenalidomide and dexamethasone in people who have failed other treatment.[1] It is taken by mouth.[3]

Common side effects include diarrhea, constipation, low platelets, low white blood cells, peripheral neuropathy, nausea, and swelling.[1] Other side effects may include liver problems.[3] Use in pregnancy may harm the baby.[3] It is a proteasome inhibitor and works by preventing protein breakdown in cells.[1]

Ixazomib was approved for medical use in the United States in 2015 and Europe in 2016.[3][1] In the United Kingdom 4 weeks of treatment costs the NHS about £6,300 as of 2021.[4] In the United States this amount costs about 11,400 USD.[5]

Medical uses

Ixazomib is used in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone for the treatment of multiple myeloma in adults after at least one prior therapy. There are no experiences with children and youths under 18 years of age.[6][7]

The study relevant for approval included 722 people. In this study it increased the median time of progression-free survival from 14.7 months to 20.6 months. 11.7% of in the ixazomib group had a complete response, versus 6.6% in the placebo group. Overall response rate (complete plus partial) was 78.3% versus 71.5%.[7][8]

A phase 3 study demonstrated a significant improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) with ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone (IRd) compared with placebo. High-risk cytogenetic abnormalities were defined as del(17p), t(4;14), and/or t(14;16); additionally, patients were assessed for 1q21 amplification. Of 722 randomized patients, 552 had cytogenetic results; 137 (25%) had high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities and 172 (32%) had 1q21 amplification alone. PFS was improved with IRd versus placebo in both high-risk and standard-risk cytogenetics subgroups: in high-risk patients, with median PFS of 21.4 versus 9.7 months; in standard-risk patients, with median PFS of 20.6 versus 15.6 months. This PFS benefit was consistent across subgroups with individual high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities, including patients with del(17p). PFS was also longer with IRd versus placebo- in patients with 1q21 amplification, and in the "expanded high-risk" group, defined as those with high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities and/or 1q21 amplification. IRd demonstrated substantial benefit compared with placebo in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma patients with high-risk and standard-risk cytogenetics, and improves the poor PFS associated with high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities.[9]

Dosage

It is given as 4 mg once a week for three weeks with one week off.[4]

Side effects

Common side effects of the ixazomib+lenalidomide+dexamethasone study therapy included diarrhoea (42% versus 36% under placebo+lenalidomide+dexamethasone), constipation (34% versus 25%), thrombocytopenia (low platelet count; 28% versus 14%), peripheral neuropathy (28% versus 21%), nausea (26% versus 21%), peripheral oedema (swelling; 25% versus 18%), vomiting (22% versus 11%), and back pain (21% versus 16%). Serious diarrhoea or thrombocytopenia occurred in 2% of patients, respectively.[7][10]

Side effects of ixazomib alone were only assessed in a small number of people. Diarrhoea grade 2 or higher was found in 24% of these patients, thrombocytopenia grade 3 or higher in 28%, and fatigue grade 2 or higher in 26%.[11]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Ixazomib and lenalidomide are teratogenic in animal studies. The latter is contraindicated in pregnant women, making this therapy regimen unsuitable for this group. It is not known whether ixazomib or its metabolites pass into the breast milk.[7][10]

Interactions

The drug has a low potential for interactions via cytochrome P450 (CYP) liver enzymes and transporter proteins. The only relevant finding in studies was a reduction of ixazomib blood levels when combined with the strong CYP3A4 inducer rifampicin. The Cmax was reduced by 54% and the area under the curve by 74% in this study.[7][10]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

At therapeutic concentrations, ixazomib selectively and reversibly inhibits the protein proteasome subunit beta type-5 (PSMB5)[10] with a dissociation half-life of 18 minutes. This mechanism is the same as of bortezomib, which has a much longer dissociation half-life of 110 minutes; the related drug carfilzomib, by contrast, blocks PSMB5 irreversibly. Proteasome subunits beta type-1 and type-2 are only inhibited at high concentrations reached in cell culture models.[12]

PSMB5 is part of the 20S proteasome complex and has enzymatic activity similar to chymotrypsin. It induces apoptosis, a type of programmed cell death, in various cancer cell lines. A synergistic effect of ixazomib and lenalidomide has been found in a large number of myeloma cell lines.[10][13]

Pharmacokinetics

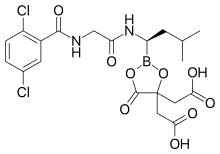

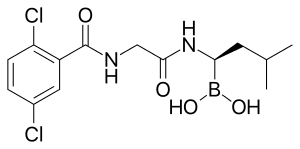

The medication is taken orally as a prodrug, ixazomib citrate, which is a boronic ester; this ester rapidly hydrolyzes under physiological conditions to its biologically active form, ixazomib, a boronic acid.[2] Absolute bioavailability is 58%, and highest blood plasma concentrations of ixazomib are reached after one hour. Plasma protein binding is 99%.[7][10]

The substance is metabolized by many CYP enzymes (percentages in vitro, at higher than clinical concentrations: CYP3A4 42.3%, CYP1A2 26.1%, CYP2B6 16.0%, CYP2C8 6.0%, CYP2D6 4.8%, CYP2C9 4.8%, CYP2C9 <1%) as well as non-CYP enzymes,[7] which could explain the low interaction potential. Clearance is about 1.86 litres per hour with a wide variability of 44% between individuals, and plasma half-life is 9.5 days. 62% of ixazomib and its metabolites are excreted via the urine (of which less than 3.5% in unchanged form) and 22% via the faeces.[7][10]

Chemistry

Ixazomib is a boronic acid and peptide analogue[13] like the older bortezomib. It contains a derivative of the amino acid leucine with the carboxylic acid group being replaced by a boronic acid; and the remainder of the molecule has been likened to phenylalanine.[12] The structure has been found through a large-scale screening of boron-containing molecules.[12]

History

The drug was developed by Takeda. It got US and European orphan drug status for multiple myeloma in 2011, and for AL amyloidosis in 2012. Takeda submitted a US new drug application for multiple myeloma in July 2015.[14] In September 2015, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted ixazomib combined with lenalidomide and dexamethasone a priority review designation for multiple myeloma.[15] On 20 November 2015, the FDA approved this combination for second-line treatment.[6]

The request for marketing authorisation in Europe was initially refused by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in May 2016 due to insufficient data showing a benefit of treatment.[16] After Takeda requested a re-examination, the EMA granted a marketing authorisation on 21 November 2016 on the condition that further efficacy studies be conducted. The approval indication is the same as in the US.[7]

Research

As of January 2017, ixazomib is also in Phase III clinical trials for the treatment of AL amyloidosis[17] and plasmacytoma of the bones,[18] and in Phase I/II trials for various other conditions.[19][20]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Ninlaro". European Medicines Agency. Archived from the original on 14 November 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- 1 2 "Ninlaro- ixazomib capsule". DailyMed. 24 March 2020. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 "Ixazomib Citrate Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- 1 2 BNF 81: March-September 2021. BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. 2021. p. 1009. ISBN 978-0857114105.

- ↑ "Ninlaro Prices, Coupons & Patient Assistance Programs". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 21 August 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- 1 2 "Press Announcements — FDA approves Ninlaro, new oral medication to treat multiple myeloma". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 20 November 2015. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Ninlaro: EPAR – Product Information" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 21 November 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 March 2018. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ↑ Moreau P, Masszi T, Grzasko N, Bahlis NJ, Hansson M, Pour L, et al. (April 2016). "Oral Ixazomib, Lenalidomide, and Dexamethasone for Multiple Myeloma". The New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (17): 1621–34. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1516282. PMID 27119237.

- ↑ Avet-Loiseau H, Bahlis NJ, Chng WJ, Masszi T, Viterbo L, Pour L, et al. (December 2017). "Ixazomib significantly prolongs progression-free survival in high-risk relapsed/refractory myeloma patients". Blood. 130 (24): 2610–2618. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-06-791228. PMID 29054911.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Haberfeld H, ed. (2016). Austria-Codex (in German). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Gupta N, Labotka R, Liu G, Hui AM, Venkatakrishnan K (June 2016). "Exposure-safety-efficacy analysis of single-agent ixazomib, an oral proteasome inhibitor, in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: dose selection for a phase 3 maintenance study". Investigational New Drugs. 34 (3): 338–46. doi:10.1007/s10637-016-0346-7. PMC 4859859. PMID 27039387.

- 1 2 3 Muz B, Ghazarian RN, Ou M, Luderer MJ, Kusdono HD, Azab AK (2016). "Spotlight on ixazomib: potential in the treatment of multiple myeloma". Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 10: 217–26. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S93602. PMC 4714737. PMID 26811670.

- 1 2 KEGG: Ixazomib Archived 2021-05-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Takeda Submits New Drug Application for Ixazomib for Patients with Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma". Takeda. 14 July 2015. Archived from the original on 27 January 2017. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ↑ "Ixazomib Granted Priority Review by the FDA for Multiple Myeloma". Targeted Oncology. 9 September 2015. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ↑ "Questions and answers on refusal of the marketing authorisation for Ninlaro" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 27 May 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 March 2018. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT01659658 for "Study of Dexamethasone Plus Ixazomib (MLN9708) or Physicians Choice of Treatment in Relapsed or Refractory Systemic Light Chain (AL) Amyloidosis" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT02516423 for "Ixazomib Citrate, Lenalidomide, Dexamethasone, and Zoledronic Acid or Zoledronic Acid Alone After Radiation Therapy in Treating Patients With Solitary Plasmacytoma of Bone" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT02420847 for "A Two-Dimensional Dose-Finding Study of Ixazomib in Combination With Gemcitabine and Doxorubicin, Followed by a Phase II Extension to Assess the Efficacy of This Combination in Metastatic, Surgically Unresectable Urothelial Cancer" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT02250300 for "MLN9708 for the Prophylaxis of Chronic Graft-versus-host Disease in Patient Undergoing Allogeneic Transplantation" at ClinicalTrials.gov

External links

| External sites: |

|

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

- "Ixazomib citrate". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2021-05-13. Retrieved 2021-01-06.