Vinblastine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Velban, others |

| Other names | vincaleukoblastine |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | intravenous |

| Defined daily dose | not established[1] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682848 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | n/a |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP3A4-mediated) |

| Elimination half-life | 24.8 hours (terminal) |

| Excretion | Biliary and kidney |

| Chemical and physical data | |

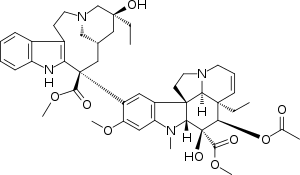

| Formula | C46H58N4O9 |

| Molar mass | 810.989 g·mol−1 |

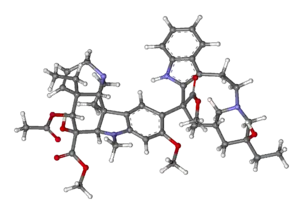

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Vinblastine (VBL), sold under the brand name Velban among others, is a chemotherapy medication, typically used with other medications, to treat a number of types of cancer.[2] This includes Hodgkin's lymphoma, non-small cell lung cancer, bladder cancer, brain cancer, melanoma, and testicular cancer.[2] It is given by injection into a vein.[2]

Most people experience some side effects.[2] Commonly it causes a change in sensation, constipation, weakness, loss of appetite, and headaches.[2] Severe side effects include low blood cell counts and shortness of breath.[2] It should not be given to people who have a current bacterial infection.[2] Use during pregnancy will likely harm the baby.[2] Vinblastine works by blocking cell division.[2]

Vinblastine was isolated in 1958.[3] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[4] As of 2014 the wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$7.70 and US$31.70 per dose.[5] In the United Kingdom it costs £13.09 per 10 mg vial.[6] It was originally obtained from the Madagascar periwinkle.[7]

Medical uses

Vinblastine is a component of a number of chemotherapy regimens, including ABVD for Hodgkin lymphoma. It is also used to treat histiocytosis according to the established protocols of the Histiocytosis Association.

Dosage

The defined daily dose is not established[1]

Side effects

Adverse effects of vinblastine include hair loss, loss of white blood cells and blood platelets, gastrointestinal problems, high blood pressure, excessive sweating, depression, muscle cramps, vertigo and headaches.[8][2]

Pharmacology

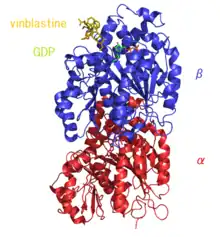

Vinblastine is a vinca alkaloid[9][3][10] and a chemical analogue of vincristine.[11][12] It binds tubulin, thereby inhibiting the assembly of microtubules.[13] Vinblastine treatment causes M phase specific cell cycle arrest by disrupting microtubule assembly and proper formation of the mitotic spindle and the kinetochore, each of which are necessary for the separation of chromosomes during anaphase of mitosis. Toxicities include bone marrow suppression (which is dose-limiting), gastrointestinal toxicity, potent vesicant (blister-forming) activity, and extravasation injury (forms deep ulcers). Vinblastine paracrystals may be composed of tightly-packed unpolymerized tubulin or microtubules.[14]

Vinblastine is reported to be an effective component of certain chemotherapy regimens, particularly when used with bleomycin, and methotrexate in VBM chemotherapy for Stage IA or IIA Hodgkin lymphomas. The inclusion of vinblastine allows for lower doses of bleomycin and reduced overall toxicity with larger resting periods between chemotherapy cycles.[15]

Mechanism of action

Microtubule-disruptive drugs like vinblastine, colcemid, and nocodazole have been reported to act by two mechanisms.[16] At very low concentrations they suppress microtubule dynamics and at higher concentrations they reduce microtubule polymer mass. Recent findings indicate that they also produce microtubule fragments by stimulating microtubule minus-end detachment from their organizing centers. Dose-response studies further indicate that enhanced microtubule detachment from spindle poles correlate best with cytotoxicity.[17]

Isolation and synthesis

Vinblastine may be isolated from the Madagascar Periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus), along with several of its precursors, catharanthine and vindoline. Extraction is costly and yields of vinblastine and its precursors are low, although procedures for rapid isolation with improved yields avoiding auto-oxidation have been developed. Enantioselective synthesis has been of considerable interest in recent years, as the natural mixture of isomers is not an economical source for the required C16’S, C14’R stereochemistry of biologically active vinblastine. Initially, the approach depends upon an enantioselective Sharpless epoxidation, which sets the stereochemistry at C20. The desired configuration around C16 and C14 can then be fixed during the ensuing steps. In this pathway, vinblastine is constructed by a series of cyclization and coupling reactions which create the required stereochemistry. The overall yield may be as great as 22%, which makes this synthetic approach more attractive than extraction from natural sources, whose overall yield is about 10%.[18] Stereochemistry is controlled through a mixture of chiral agents (Sharpless catalysts), and reaction conditions (temperature, and selected enantiopure starting materials).[19]

History

Vinblastine was first isolated by Robert Noble and Charles Thomas Beer at the University of Western Ontario from the Madagascar periwinkle plant. Vinblastine's utility as a chemotherapeutic agent was first suggested by its effect on the body when an extract of the plant was injected in rabbits to study the plant's supposed anti-diabetic effect. (A tea made from the plant was a folk-remedy for diabetes.) The rabbits succumbed to a bacterial infection, due to a decreased number of white blood cells, so it was hypothesized that vinblastine might be effective against cancers of the white blood cells such as lymphoma.[20]

References

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Vinblastine Sulfate". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2015-01-02. Retrieved Jan 2, 2015.

- 1 2 Ravina, Enrique (2011). The evolution of drug discovery : from traditional medicines to modern drugs (1. Aufl. ed.). Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. p. 157. ISBN 9783527326693. Archived from the original on 2017-08-01.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ "Vinblastine". Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. p. 593. ISBN 9780857111562.

- ↑ Liljefors, Tommy; Krogsgaard-Larsen, Povl; Madsen, Ulf (2002). Textbook of Drug Design and Discovery (Third ed.). CRC Press. p. 550. ISBN 9780415282888. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20.

- ↑ "Vinblastine sulfate- vinblastine sulfate injection". DailyMed. 31 December 2019. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ↑ van Der Heijden R, Jacobs DI, Snoeijer W, Hallard D, Verpoorte R (March 2004). "The Catharanthus alkaloids: pharmacognosy and biotechnology". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 11 (5): 607–28. doi:10.2174/0929867043455846. PMID 15032608.

- ↑ Cooper, Raymond; Deakin, Jeffrey John (2016). "Africa's gift to the world". Botanical Miracles: Chemistry of Plants That Changed the World. CRC Press. pp. 46–51. ISBN 9781498704304. Archived from the original on 2017-08-01.

- ↑ Keglevich P, Hazai L, Kalaus G, Szántay C (May 2012). "Modifications on the basic skeletons of vinblastine and vincristine". Molecules. 17 (5): 5893–914. doi:10.3390/molecules17055893. PMC 6268133. PMID 22609781.

- ↑ Sears JE, Boger DL (March 2015). "Total synthesis of vinblastine, related natural products, and key analogues and development of inspired methodology suitable for the systematic study of their structure-function properties". Accounts of Chemical Research. 48 (3): 653–62. doi:10.1021/ar500400w. PMC 4363169. PMID 25586069.

- ↑ Altmann, Karl-Heinz (2009). "Preclinical Pharmacology and Structure-Activity Studies of Epothilones". In Mulzer, Johann H. (ed.). The Epothilones: An Outstanding Family of Anti-Tumor Agents: From Soil to the Clinic. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 157–220. ISBN 9783211782071. Archived from the original on 2017-09-11.

- ↑ Starling D (January 1976). "Two ultrastructurally distinct tubulin paracrystals induced in sea-urchin eggs by vinblastine sulphate" (PDF). Journal of Cell Science. 20 (1): 79–89. PMID 942954. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-01-13.

- ↑ Gobbi PG, Broglia C, Merli F, Dell'Olio M, Stelitano C, Iannitto E, et al. (December 2003). "Vinblastine, bleomycin, and methotrexate chemotherapy plus irradiation for patients with early-stage, favorable Hodgkin lymphoma: the experience of the Gruppo Italiano Studio Linfomi". Cancer. 98 (11): 2393–401. doi:10.1002/cncr.11807. hdl:11380/4847. PMID 14635074.

- ↑ Jordan MA, Wilson L (April 2004). "Microtubules as a target for anticancer drugs". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 4 (4): 253–65. doi:10.1038/nrc1317. PMID 15057285.

- ↑ Yang H, Ganguly A, Cabral F (October 2010). "Inhibition of cell migration and cell division correlates with distinct effects of microtubule inhibiting drugs". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 285 (42): 32242–50. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.160820. PMC 2952225. PMID 20696757.

- ↑ Kuehne ME, Matson PA, Bornmann WG (1991). "Enantioselective Syntheses of Vinblastine, Leurosidine, Vincovaline, and 20'-epi-Vincovaline". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 56 (2): 513–528. doi:10.1021/jo00002a008.

- ↑ Yokoshima S, Tokuyama H, Fukuyama T (2009). "Total Synthesis of (+)-Vinblastine: Control of the Stereochemistry at C18′". The Chemical Record. 10 (2): 101–118. doi:10.1002/tcr.200900025.

- ↑ Noble RL, Beer CT, Cutts JH (December 1958). "Role of chance observations in chemotherapy: Vinca rosea". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 76 (3): 882–94. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1958.tb54906.x. PMID 13627916.

External links

| External sites: |

|

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |