Minoxidil

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Rogaine, others |

| Clinical data | |

| Main uses | High blood pressure, male-pattern hair loss[4][5] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth, topical |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Systemic: Monograph Topical: Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682608 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Metabolism | Primarily liver |

| Elimination half-life | 4 hours[6] |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Chemical and physical data | |

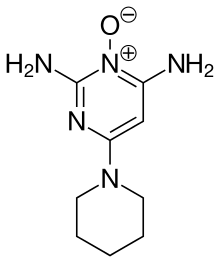

| Formula | C9H15N5O |

| Molar mass | 209.253 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 248 °C (478 °F) |

| Solubility in water | <1 mg/mL (20 °C) |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Minoxidil is a medication used to treat high blood pressure and male-pattern hair loss.[4][5] For high blood pressure, it is only recommended when severe and not controllable with a diuretic and a beta blocker.[7] For male-pattern hair loss it is effective in both males and females.[5] For high blood pressure it is taken by mouth while for hair loss it is applied to the skin.[7][5]

Common side effects when taken by mouth include swelling, pericardial effusion, hair growth, and nausea.[4] Other side effects may include low white blood cells, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and angina.[7] Common side effects when applied to the skin include itchiness and local irritation.[5] Safety in pregnancy and breastfeeding is unclear and such use is not recommended.[8] As a high blood pressure medication it works by dilating blood vessels.[6] How it works in hair loss is not entirely clear.[5]

Minoxidil was approved for medical use in the United States in 1979.[4] In the United States it is available as a generic medication by prescription in tablet form and over the counter for use on the skin.[4][5] At a dose of 5 mg per day it costs the NHS about 9 pounds per month as of 2020.[7]

Medical uses

Hair loss

Minoxidil, applied topically, is widely used for hair loss. It is effective in helping promote hair growth in people with androgenic alopecia regardless of sex.[9] Minoxidil must be used indefinitely for continued support of existing hair follicles and the maintenance of any experienced hair regrowth.[10] Its effect in people with alopecia areata is unclear.[11]

High blood pressure

For high blood pressure, it is only recommended when severe and not controllable with a diuretic and a beta blocker.[7] The starting dose is generally 5 mg a day which may be increased by 5 to 10 mg every 3 or more days to a maximum of 100 mg.[7] It should be started at half that dose in the elderly.[5]

Side effects

Minoxidil is generally well tolerated, but common side effects include burning or irritation of the eye, itching, redness or irritation at the treated area, and unwanted hair growth elsewhere on the body. Exacerbation of hair loss/alopecia has been reported.[12][13] Severe allergic reactions may include rash, hives, itching, difficulty breathing, tightness in the chest, swelling of the mouth, face, lips, or tongue, chest pain, dizziness, fainting, tachycardia, headache, sudden and unexplained weight gain, or swelling of the hands and feet.[14] Temporary hair loss is a common side effect of minoxidil treatment.[15] Manufacturers note that minoxidil-induced hair loss is a common side effect and describe the process as "shedding".

Alcohol and propylene glycol present in some topical preparations may dry the scalp, resulting in dandruff and contact dermatitis.[16]

Side effects of oral minoxidil may include swelling of the face and extremities, rapid and irregular heartbeat, lightheadedness, cardiac lesions, and focal necrosis of the papillary muscle and subendocardial areas of the left ventricle.[13] Cases of allergic reactions to minoxidil or the non-active ingredient propylene glycol, which is found in some topical minoxidil formulations, have been reported. Pseudoacromegaly is an extremely rare side effect reported with large doses of oral minoxidil.[17]

Minoxidil may cause hirsutism, although it is exceedingly rare and reversible by discontinuation of the drug.[18]

Minoxidil is suspected to be highly toxic to cats, as there are reported cases of cats dying shortly after coming in contact with minimal amounts of the substance.[19][20]

Mechanism of action

The mechanism by which minoxidil promotes hair growth is not fully understood. Minoxidil is a potassium channel opener,[21] causing hyperpolarization of cell membranes. Theoretically, by widening blood vessels and opening potassium channels, it allows more oxygen, blood, and nutrients to the follicles. This may cause follicles in the telogen phase to shed, which are then replaced by thicker hairs in a new anagen phase. Minoxidil is a prodrug that is converted by sulfation via the sulfotransferase enzyme SULT1A1 to its active form, minoxidil sulfate.

Minoxidil is less effective when the area of hair loss is large. In addition, its effectiveness has largely been demonstrated in younger men who have experienced hair loss for less than 5 years. Minoxidil use is indicated for central (vertex) hair loss only.[22] Two clinical studies are being conducted in the US for a medical device that may allow patients to determine if they are likely to benefit from minoxidil therapy.[23]

History

Initial application

Minoxidil was developed in the late 1950s by the Upjohn Company (later became part of Pfizer) to treat ulcers. In trials using dogs, the compound did not cure ulcers, but proved to be a powerful vasodilator. Upjohn synthesized over 200 variations of the compound, including the one it developed in 1963 and named minoxidil.[24] These studies resulted in FDA approving minoxidil (with the trade name 'Loniten') in the form of oral tablets to treat high blood pressure in 1979.[25]

Hair growth

When Upjohn received permission from the FDA to test the new drug as medicine for hypertension they approached Charles A. Chidsey MD, Associate Professor of Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.[24] He conducted two studies,[26][27] the second study showing unexpected hair growth. Puzzled by this side-effect, Chidsey consulted Guinter Kahn (who while a dermatology resident at the University of Miami had been the first to observe and report hair development on patients using the minoxidil patch) and discussed the possibility of using minoxidil for treating hair loss.

Kahn along with his colleague Paul J. Grant MD had obtained a certain amount of the drug and conducted their own research, since they were first to make the side effect observation. Neither Upjohn or Chidsey at the time were aware of the side effect of hair growth.[28] The two doctors had been experimenting with a 1% solution of minoxidil mixed with several alcohol-based liquids.[29] Both parties filed patents to use the drug for hair loss prevention, which resulted in a decade-long trial between Kahn and Upjohn, which ended with Kahn's name included in a consolidated patent (U.S. #4,596,812 Charles A Chidsey, III and Guinter Kahn) in 1986 and royalties from the company to both Kahn and Grant.[28]

Meanwhile the effect of minoxidil on hair loss prevention was so clear that in the 1980s physicians were prescribing Loniten off-label to their balding patients.[25]

In August 1988, the FDA finally approved the drug for treating baldness in men[25][29] under the trade name "Rogaine" (FDA rejected Upjohn's first choice, Regain, as misleading[30]). The agency concluded that although "the product will not work for everyone", 39% of the men studied had "moderate to dense hair growth on the crown of the head".[30]

In 1991, Upjohn made the product available for women.[29]

On February 12, 1996, the FDA approved both the over-the-counter sale of the drug and the production of generic formulations of minoxidil.[25] Upjohn replied to that by lowering prices to half the price of the prescription drug[29] and by releasing a prescription 5% formula of Rogaine in 1997.[25]

In 1998, a 5% formulation of minoxidil was approved for nonprescription sale by the FDA.[31]

As of 2014, it was the only topical product that is FDA-approved for androgenic hair loss.[9]

The drug is available over the counter in many countries, including United Kingdom[10] (topical only), United States (topical only), Sweden, and Germany (available from registered pharmacies only).

Trade names

As of June 2017, Minoxidil was marketed under many trade names worldwide: Alomax, Alopek, Alopexy, Alorexyl, Alostil, Aloxid, Aloxidil, Anagen, Apo-Gain, Axelan, Belohair, Boots Hair Loss Treatment, Botafex, Capillus, Carexidil, Coverit, Da Fei Xin, Dilaine, Dinaxcinco, Dinaxil, Ebersedin, Eminox, Folcare, Guayaten, Hair Grow, Hair-Treat, Hairgain, Hairgaine, Hairgrow, Hairway, Headway, Inoxi, Ivix, Keranique, Lacovin, Locemix, Loniten, Lonnoten, Lonolox, Lonoten, Loxon, M E Medic, Maev-Medic, Mandi, Manoxidil, Mantai, Men's Rogaine, Minodil, Minodril, Minostyl, Minovital, Minox, Minoxi, Minoxidil, Minoxidilum, Minoximen, Minoxiten, Minscalp, Mintop, Modil, Morr, Moxidil, Neo-Pruristam, Neocapil, Neoxidil, Nherea, Noxidil, Oxofenil, Pilfud, Pilogro, Pilomin, Piloxidil, Recrea, Regain, Regaine, Regaxidil, Regro, Regroe, Regrou, Regrowth, Relive, Renobell Locion, Reten, Rexidil, Rogaine, Rogan, Si Bi Shen, Splendora, Superminox, Trefostil, Tricolocion, Tricoplus, Tricovivax, Tricoxane, Trugain, Tugain, Unipexil, Vaxdil, Vius, Womens Regaine, Xenogrow, Xue Rui, Ylox, and Zeldilon.[32] It was also marketed as combination drug with amifampridine under the brand names Gainehair and Hair 4 U, and as a combination with tretinoin and clobetasol under the brand name Sistema GB.[32]

See also

- Kopexil, an analog of minoxidil missing the piperidine substituent

- Pinacidil

- Diazoxide

- Finasteride

- Dutasteride

References

- ↑ product, sigma. "M4145 Sigma ≥99% (TLC)". sigmaaldrich.com. sigma. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ↑ cayman chemical, company. "safety data sheet" (PDF). caymanchem.com. cayman chemical company. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 October 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ↑ archives, dailymed. "loniten- minoxidil tablet". dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. dailymed. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Minoxidil Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. AHFS. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Minoxidil topical Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. AHFS. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- 1 2 Benowitz, Neal L. (2020). "11. Antihypertensive agents". In Katzung, Bertram G.; Trevor, Anthony J. (eds.). Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (15th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 183-186. ISBN 978-1-260-45231-0. Archived from the original on 2021-10-10. Retrieved 2021-12-05.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 BNF 79. London: Pharmaceutical Press. March 2020. p. 186. ISBN 978-0857113658.

- ↑ "Minoxidil (Loniten) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- 1 2 Varothai S, Bergfeld WF (July 2014). "Androgenetic alopecia: an evidence-based treatment update". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 15 (3): 217–30. doi:10.1007/s40257-014-0077-5. PMID 24848508. S2CID 31245042.

- 1 2 "Minoxidil Regular Strength". UK Electronic Medicines Compendium. 18 August 2015. Archived from the original on 8 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ↑ Hordinsky M, Donati A (July 2014). "Alopecia areata: an evidence-based treatment update". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 15 (3): 231–46. doi:10.1007/s40257-014-0086-4. PMID 25000998. S2CID 32253.

- ↑ "Rogaine Side Effects in Detail - Drugs.com". drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2017-09-22.

- 1 2 "Minoxidil Official FDA information, side effects and uses". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2017-09-22.

- ↑ "Rogaine Side Effects in Detail - Drugs.com". drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2017-09-22.

- ↑ "FAQs for Men - Hair Growth Education - ROGAINE®". www.rogaine.com. Archived from the original on 2009-11-10. Retrieved 2009-11-20.

- ↑ "Dandruff and Seborrheic Dermatitis". Medscape.com. Archived from the original on 2010-10-28. Retrieved 2009-10-09.

- ↑ Nguyen KH, Marks JG (June 2003). "Pseudoacromegaly induced by the long-term use of minoxidil". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 48 (6): 962–5. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.325. PMID 12789195.

- ↑ Dawber RP, Rundegren J (May 2003). "Hypertrichosis in females applying minoxidil topical solution and in normal controls". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 17 (3): 271–5. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00621.x. PMID 12702063.

- ↑ "Minoxidil Warning". www.showcatsonline.com. Archived from the original on 2019-03-08.

- ↑ DeClementi, Camille; Bailey, Keith L.; Goldstein, Spencer C.; Orser, Michael Scott (November 2004). "Suspected toxicosis after topical administration of minoxidil in 2 cats". Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care. 14 (4): 287–292. doi:10.1111/j.1476-4431.2004.04014.x.

- ↑ Wang T (February 2003). "The effects of the potassium channel opener minoxidil on renal electrolytes transport in the loop of henle". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 304 (2): 833–40. doi:10.1124/jpet.102.043380. PMID 12538840. S2CID 6948410.

- ↑ Scow DT, Nolte RS, Shaughnessy AF (April 1999). "Medical treatments for balding in men". American Family Physician. 59 (8): 2189–94, 2196. PMID 10221304. Archived from the original on 2012-09-28.

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT02198261 for "Minoxidil Response Testing in Males With Androgenetic Alopecia" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- 1 2 Douglas Martin (2014-09-19). "Guinter Kahn, Inventor of Baldness Remedy, Dies at 80". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2014-11-05. Retrieved 2015-05-11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Conrad, Peter (2008). "Extension". The Medicalization of Society: On the Transformation of Human Conditions into Treatable Disorders. JHU Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0801892349. Archived from the original on 2016-04-11. Retrieved 2015-05-11. (Google Books)

- ↑ Gilmore E, Weil J, Chidsey C (March 1970). "Treatment of essential hypertension with a new vasodilator in combination with beta-adrenergic blockade". The New England Journal of Medicine. 282 (10): 521–7. doi:10.1056/NEJM197003052821001. PMID 4391708.

- ↑ Gottlieb TB, Katz FH, Chidsey CA (March 1972). "Combined therapy with vasodilator drugs and beta-adrenergic blockade in hypertension. A comparative study of minoxidil and hydralazine". Circulation. 45 (3): 571–82. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.45.3.571. PMID 4401051.

- 1 2 Norman M. Goldfarb (March 2006). "When Patents Became Interesting in Clinical Research" (PDF). The Journal of Clinical Research Best Practices. 2 (3). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 2015-05-11.

- 1 2 3 4 Will Lester (May 13, 1996). "Hair-rasing tale: no fame for men who discovered Rogaine". The Daily Gazette. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2015-05-11.

- 1 2 Kuntzman, Gersh (2001). Hair!: Mankind's Historic Quest to End Baldness. Random House Publishing Group. p. 172. ISBN 978-0679647096. Archived from the original on 2016-04-21. Retrieved 2015-05-11. (Google Books)

- ↑ Pray, Stephen W. (2006). Nonprescription Product Therapeutics. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 663. ISBN 978-0781734981. Archived from the original on 2016-04-03. Retrieved 2015-05-11. (Google Books)

- 1 2 Drugs.com International brand names for minoxidil Archived 2017-08-08 at the Wayback Machine Page accessed June 26, 2017

External links

- "Minoxidil". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2020-10-24. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- "Minoxidil Topical". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 2020-09-13. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

| Identifiers: |

|---|