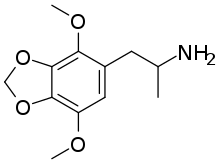

DMMDA

2,5-Dimethoxy-3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (DMMDA) is a psychedelic drug of the phenethylamine and amphetamine chemical classes.[1] It was first synthesized by Alexander Shulgin and was described in his book PiHKAL.[1] Shulgin listed the dosage as 30–75 mg and the duration as 6–8 hours.[1] He reported DMMDA as producing LSD-like images, mydriasis, ataxia, and time dilation.[1]

| |

| |

| Legal status | |

|---|---|

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C12H19NO4 |

| Molar mass | 241.287 g·mol−1 |

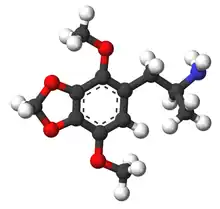

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Pharmacology

The mechanism behind DMMDA's hallucinogenic effects has not been specifically established, however Shulgin describes that a 75 milligram dose of DMMDA is equivalent to a 75–100 microgram dose of LSD. LSD is a known 5-HT2A partial agonist.[1] DMMDA also has an affinity for the 5-HT2A receptor in the human brain.[2] Because similar chemicals, such as MDA and MMDA, act as agonists on the 5-HT2A, it is likely that DMMDA also acts as an agonist of the 5-HT2A receptor.[3][4] This may suggest that the hallucinogenic effects of DMMDA result from its agonism of the 5-HT2A receptor in the human brain. DMMDA also has lower affinities for other serotonin receptors, such as the 5-HT2B, 5-HT2C and 5-HT1B receptor as well as serotonin, dopamine and norepinephrine transporters, which may contribute to DMMDA's psychoactive effects.[2] DMMDA-2's and DMMDA-3’s affinities for the 5-HT2A receptor are almost the same as DMMDA’s.[5][6] The as of yet unnamed 4,5-dimethoxy-2,3-methylenedioxyamphetamine's affinity for the 5-HT2A is slighly lower than DMMDA's; the affinity for the receptor stands at around 70% that of DMMDA.[7][2] The two as of yet unnamed remaining isomers of DMMDA are 4,6-dimethoxy-2,3-methylenedioxyamphetamine and 5,6-dimethoxy-2,3-methylenedioxyamphetamine, which both have an affinity for the 5-HT2A receptor of around 65-70% that of DMMDA.[8][9]

Chemistry

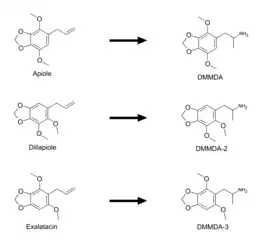

Shulgin explains in his book that DMMDA has 6 isomers similar to TMA.[1] DMMDA-2 is the only other isomer that has been synthesized as of yet. DMMDA-3 could be made from exalatacin (1-allyl-2,6-dimethoxy-3,4-methylenedioxybenzene). Exalatacin can be found in the essential oil of both Crowea exalata and Crowea angustifolia var. angustifolia.[10] In other words, exalatacin is an isomer of both apiole and dillapiole, which can be used to make DMMDA and DMMDA-2 respectively. Exalatacin is almost identical to apiole and dillapiole, but differs from them in its positioning of its methoxy groups, which are in the 2 and 6 positions.[10] Additionally, yet another isomer of DMMDA could be made from pseudo-dillapiole or 4,5-dimethoxy-2,3-methylenedioxyallylbenzene.[11]

Precursors in the synthesis of DMMDA and analogs

Precursors in the synthesis of DMMDA and analogs

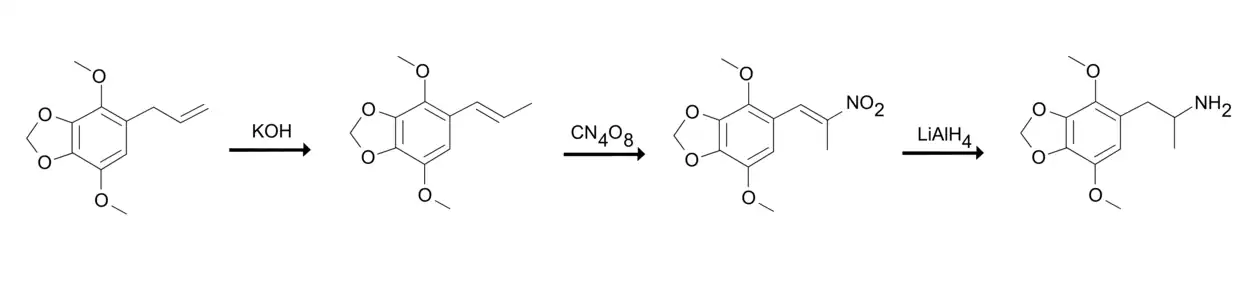

Synthesis

Shulgin describes the synthesis of DMMDA from apiole in his book PiHKAL.[1] Apiole is subjected to an isomerization reaction to yield isoapiole by adding to solution of ethanolic potassium hydroxide and holding the solution at a steam bath.[1] The isoapiole is then nitrated to 2-nitro-isoapiole or 1-(2,3-dimethoxy-3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl)-2-nitropropene by adding it to a stirred solution of acetone and pyridine at ice-bath temperatures and treating the solution with tetranitromethane. The pyridine acts as a catalyst in this reaction.[1] The 2-nitro-isoapiole is finally reduced to freebase DMMDA by adding it to a well-stirred and refluxing suspension of diethylether and lithium aluminium hydride under an inert atmosphere (e.g. helium).[1] Finally, the freebase DMMDA converted into its hydrochloride salt.[1]

Shulgin's synthesis of DMMDA is reasonably unsafe, since it involves the use of tetranitromethane, which is toxic, carcinogenic and prone to detonating.[12] DMMDA can be made from apiole via other safer methods. Among other methods, DMMDA can be synthesize from apiole via the intermediate chemical 2,5-dimethoxy-3,4-methylenedioxyphenylpropan-2-one or DMMDP2P in the same manner as MDA is made from safrole. DMMDP2P can be made from apiole via a Wacker oxidation with benzoquinone. DMMDP2P can be alternatively made by subjecting apiole to an isomerisation reaction to yield isoapiole followed by a Peracid oxidation and finally a hydrolytic dehydration.[13] Then the DMMDP2P can then be subjected to a reductive amination with a source of nitrogen, such as ammonium chloride, and a reducing agent, such as sodium cyanoborohydride or an amalgam of mercury and aluminium, to yield freebase DMMDA.[14]

Alexander Shulgin's synthesis of DMMDA.

Alexander Shulgin's synthesis of DMMDA.

References

- Shulgin A, Shulgin A (1991). Pihkal: A Chemical Love Story. Transform Press. ISBN 0-9630096-0-5.

- Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (2022). "SwissTargetPrediction". Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. Retrieved 2022-12-21.

- Giuseppe Di Giovanni; Vincenzo Di Matteo; Ennio Esposito (2008). Serotonin–dopamine Interaction: Experimental Evidence and Therapeutic Relevance. Elsevier. pp. 294–. ISBN 978-0-444-53235-0.

- Zhang Z, An L, Hu W, Xiang Y (April 2007). "3D-QSAR study of hallucinogenic phenylalkylamines by using CoMFA approach". Journal of Computer-aided Molecular Design. 21 (4): 145–53. Bibcode:2007JCAMD..21..145Z. doi:10.1007/s10822-006-9090-y. PMID 17203365. S2CID 25343432.

- Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (2022). "SwissTargetPrediction". Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. Retrieved 2022-12-21.

- Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (2022). "SwissTargetPrediction". Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. Retrieved 2022-12-21.

- Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (2022). "SwissTargetPrediction". Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. Retrieved 2022-12-21.

- Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (2022). "SwissTargetPrediction". Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. Retrieved 2022-12-21.

- Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (2022). "SwissTargetPrediction". Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. Retrieved 2022-12-21.

- Brophy JJ, Goldsack RJ, Punruckvong A, Forster PI, Fookes CJ (July 1997). "Essential oils of the genus Crowea (Rutaceae)". Journal of Essential Oil Research. 9 (4): 401–409. doi:10.1080/10412905.1997.9700740.

- US patent 4,876,277, Basil A. Burke, Muraleedharan G. Nair, "Antimicrobial/antifungal compositions", issued 1989-10-24, assigned to Plant Cell Research Institute, Inc., Dublin, Calif.

- National Toxicology Program (2011). "Tetranitromethane" (PDF). Report On Carcinogens (12th ed.). National Toxicology Program. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-01-31. Retrieved 2012-08-14.

- Cox M, Klass G, Morey S, Pigou P (July 2008). "Chemical markers from the peracid oxidation of isosafrole". Forensic Science International. 179 (1): 44–53. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2008.04.009. PMID 18508215.

- Braun U, Shulgin AT, Braun G (February 1980). "Centrally active N-substituted analogs of 3,4-methylenedioxyphenylisopropylamine (3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine)". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 69 (2): 192–195. doi:10.1002/jps.2600690220. PMID 6102141.