Bisantrene

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

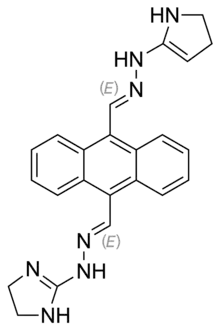

| Formula | C22H22N8 |

| Molar mass | 398.474 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Bisantrene, trademarked as Zantrene, is an anthracenyl bishydrazone with anthracycline-like antineoplastic activity. Bisantrene intercalates with and disrupts the configuration of DNA, resulting in DNA single-strand breaks, DNA-protein crosslinking, and inhibition of DNA replication. This agent is similar to doxorubicin in activity, but unlike anthracyclines like doxorubicin, exhibits little cardiotoxicity.[1]

Bisantrene has recently been identified a potent (IC50 142nM) Fat Mass and Obesity (FTO) associated protein a m6A RNA demethylase.[2]

Bisantrene is currently undergoing a number of Phase II trials to assess the efficacy of fighting hard to target cancers and understand any negative side effects that could occur.

Medical uses

Clinical trials of Bisantrene in the 1980s showed efficacy in a range of leukaemias (including Acute Myeloid Leukaemia), breast cancer, and ovarian cancer.[2]

Side effects

High doses of bisantrene (above 200mg/m2/day) cause side effects typical of anthracycline chemotherapeutics. Common side effects include hair loss, bone marrow suppression, vomiting, rash, and inflammation of the mouth.

Unlike other anthracycline chemotherapeutics, Bisantrene shows low levels of cardiotoxicity. In a Phase III metastatic breast cancer clinical, patients were exposed to cumulative doses in excess of 5440 mg/m2 without developing cardiac damage.[2] The same study observed significantly lower rates of hair loss and nausea compared to patients given doxorubicin.[3]

Mechanism of action

Bisantrene contains an appropriately sized planar electron-rich chromophore to be a DNA intercalating agent, and in vitro, it is a potent inhibitor of DNA and RNA synthesis.[2]

History

Bisantrene was developed by Lederle Laboratories during the 1970s, a subsidiary of American Cyanamid, as an less cardiotoxic alternative to anthracyclines. Across the 1980's and early 1990's, over 40 clinical trials were conducted using Bisantrene. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) undertook a large scale trial using Bisantrene under the name "Orange Crush", including a range of preclinical trials which found bisantrene to be inactive when taken orally, though was found to be efficacy towards some cancer cells intravenous, intraperitoneal, or subcutaneous.[4]

In the 1980's, forty-four patients with metastatic breast cancer who had undergone extensive combination chemotherapy with doxorubicin and had failed to respond to the combination, were treated with bisantrene. From 40 patients that were evaluated, 9 showed a partial response, and 18 showed the cancer was not progressive but stablised.[5]

Bisantrene was approved for human medical use in France in 1990 to target Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) cancers.[4]

It has undergone 46 Phase II trials with 1,800 patients to test its efficacy against fighting cancer cells.

The drug was delisted in the early 1990’s due to a series of pharmaceutical mergers and acquisitions.

Currently patents are held by Race Oncology Limited and further Phase II and Phase III trials are being initiated to assess its efficacy as a targeted oncology cancer treatment.[6]

Society and culture

Names

Its chemical name is 9, 10-antrhracenedicarboxaldehydebis [(4, 5-dihydro-1H-imidazole-2-yl) hydrazine] dihydrochloride. Bisantrene was given the nickname “Orange Crush” in the 1980s due to its fluorescent orange color when in solution.[7]

Race Oncology Ltd are reviving Bisantrene in new clinical trials and have trademarked it for use under Zantrene.[8]

Research

In 1990 bisantrene was examined to understand the various cardiac oxygen metabolism effects against other anthracycline antibiotics. It was found that it did not significantly enhance cardiac reactive oxygen metabolism and therefore, was not a cause of hydrogen peroxide by heart sarcosomes and submitochondrial particles compared to other anthracycline antibiotics.[9]

In 1990, the drug was tested on fresh clonogenic leukemia patients in a sample size of 15. Bisantrene proved effective in 12 out of 15 acute non lymphoid leukemias (ANLL) cases, inhibiting blast colony growth in a dose-dependent, time-dependent way. Three cases were unresponsive both in vitro and in vivo.[10]

In May 2020, Sheba Medical Centre initiated a Phase II clinical trial[11] with relapsed or refractory Acute Myeloid Leukaemia participants who had failed three prior rounds of treatment with other cancer fighting drugs. Bisantrene was found to be well tolerated with only a single round of treatment and had an overall clinical response rate of 40% (n=10).[12]

In June 2020, City of Hope National Medical Center identified Bisantrene as a potent small molecule that suppressed tumour growth in multiple cancers when other treatments were not effective.[13]

George Clinical is currently scoping a proof-of-concept Phase I/II breast cancer clinical trial in combination with cyclophosphamide.[14]

Race Oncology in conjunction with the University of Newcastle discovered in a preclinical study that Bisantrene not only helped fight cancer cells, but also protected human heart muscle cells from anthracycline-induced chemotherapy death. Anthracyclines are current standard of care when treating cancer, but have serious adverse impacts on the heart when used.[15]

References

- ↑ PubChem. "Bisantrene". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2021-03-17.

- 1 2 3 4 Spiegel RJ, Blum RH, Levin M, Pinto CA, Wernz JC, Speyer JL, Hoffman KS, Muggia FM (January 1982). "Phase I clinical trial of 9,10-anthracene dicarboxaldehyde (Bisantrene) administered in a five-day schedule" (PDF). Cancer Research. 42 (1): 354–8. PMID 7053862.

- ↑ Cowan JD, Neidhart J, McClure S, Coltman CA, Gumbart C, Martino S, et al. (August 1991). "Randomized trial of doxorubicin, bisantrene, and mitoxantrone in advanced breast cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group study". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 83 (15): 1077–84. doi:10.1093/jnci/83.15.1077. PMID 1875415.

- 1 2 Rothman J (July 2017). "The Rediscovery of Bisantrene: A Review of the Literature" (PDF). International Journal of Cancer Research & Therapy. 2 (2): 1–10. ISSN 2476-2377.

- ↑ Yap, Hwee-Yong; Yap, Boh-Seng; Blumenschein, George; Barnes, Brian; Schell, Frank; Bodey, Gerald (March 1983). "Bisantrene, an Active New Drug in the Treatment of Metastatic Breast Cancer" (PDF). Cancer Research. 43 (3): 1402–1404. PMID 6825109.

- ↑ "United States Patent Application Process" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-07-12.

- ↑ "Bisantrene Hydrochloride (Code C77218)". 28 June 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-07-12. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- ↑ "PEER-REVIEWED "THE REDISCOVERY OF BISANTRENE" PUBLISHED" (PDF). 20 July 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-07-12.

- ↑ Doroshow JH, Davies KJ (October 1983). "Comparative cardiac oxygen radical metabolism by anthracycline antibiotics, mitoxantrone, bisantrene, 4'-(9-acridinylamino)-methanesulfon-m-anisidide, and neocarzinostatin". Biochemical Pharmacology. 32 (19): 2935–9. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(83)90399-4. PMID 6313012.

- ↑ Visani G, Rizzi S, Tosi P, Cenacchi A, Gamberi B, Lemoli RM, et al. (November 1990). "In vitro effects of bisantrene on fresh clonogenic leukemia cells: a preliminary study on 15 cases". Haematologica. 75 (6): 527–31. PMID 2098293.

- ↑ Nagler, Prof Arnon (6 August 2020). "Bisantrene for Relapsed /Refractory AML - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov". clinicaltrials.gov. Retrieved 2021-03-17.

- ↑ Australian Securities Exchange (16 June 2020). "Impressive 40% clinical response rate in Phase 2 Bisantrene AML Trial". Australian Securities Exchange. Archived from the original on 2021-04-21.

- ↑ Zen V (16 June 2020). "Two new, powerful small molecules may be able to kill cancers that other therapies can't". City of Hope National Medical Center. Archived from the original on 2020-06-17.

- ↑ "Race Oncology Breast Cancer Clinical Trial Initiated with George Clinical | George Clinical | Leading Asia Pacific CRO". George Clinical. 2020-12-11. Retrieved 2021-03-17.

- ↑ "Breakthrough Chemotherapy Heart Protection Discovery for Australian Biotech". PR News Wire Asia. 22 November 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.