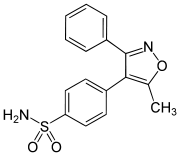

Valdecoxib

Valdecoxib is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used in the treatment of osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and painful menstruation and menstrual symptoms. It is a selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor. It was patented in 1995.[1]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Bextra |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 83% |

| Protein binding | 98% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (CYP3A4 and 2C9 involved) |

| Elimination half-life | 8 to 11 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.229.918 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C16H14N2O3S |

| Molar mass | 314.36 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

Valdecoxib was manufactured and marketed under the brand name Bextra by G. D. Searle & Company as an anti-inflammatory arthritis drug.[2] It was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration on November 20, 2001, to treat arthritis and menstrual cramps.[3][4] and was available by prescription in tablet form until 2005 when the FDA requested that Pfizer withdraw Bextra from the American market.[5] The FDA cited "potential increased risk for serious cardiovascular (CV) adverse events," an "increased risk of serious skin reactions" and the "fact that Bextra has not been shown to offer any unique advantages over the other available NSAIDs."[5]

In 2009 Bextra was at the center of the "largest health care fraud settlement and the largest criminal fine of any kind ever."[3][6] Pfizer paid a $2.3 billion civil and criminal fine. Pharmacia & Upjohn, a Pfizer subsidiary, violated the United States Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act for misbranding Bextra "with the intent to defraud or mislead."[2]

A water-soluble and injectable prodrug of valdecoxib, parecoxib is marketed in the European Union under the tradename Dynastat.

Uses until 2005

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved valdecoxib for the treatment of osteoarthritis, adult rheumatoid arthritis, and primary dysmenorrhea.[7]

Valdecoxib was also used off-label for controlling acute pain and various types of surgical pain.[7]

Side-effects and withdrawal from market

On April 7, 2005, Pfizer withdrew Bextra from the U.S. market on recommendation by the FDA, citing an increased risk of heart attack and stroke and also the risk of a serious, sometimes fatal, skin reaction. This was a result of recent attention to prescription NSAIDs, such as Merck's Vioxx. Other reported side-effects were angina and Stevens–Johnson syndrome.

Pfizer first acknowledged cardiovascular risks associated with Bextra in October 2004. The American Heart Association soon after was presented with a report indicating patients using Bextra while recovering from heart surgery were 2.19 times more likely to suffer a stroke or heart attack than those taking placebos.

In a large study published in The Journal of the American Medical Association in 2006, valdecoxib appeared less adverse for renal (kidney) disease and heart arrhythmia compared to Vioxx, however elevated renal risks were slightly suggested.[8]

2009 settlement for off-label uses promotions

On September 2, 2009, the United States Department of Justice fined Pfizer $2.3 billion after one of its subsidiaries, Pharmacia & Upjohn Company, pleaded guilty to marketing four drugs including Bextra "with the intent to defraud or mislead."[9] Pharmacia & Upjohn admitted to criminal conduct in the promotion of Bextra, and agreed to pay the largest criminal fine ever imposed in the United States for any matter, $1.195 billion.[10] A former Pfizer district sales manager was indicted and sentenced to home confinement for destroying documents regarding the illegal promotion of Bextra.[11][12] In addition, a Regional Manager pleaded guilty to distribution of a mis-branded product, and was fined $75,000 and twenty-four months on probation.[13]

The remaining $1 billion of the fine was paid to resolve allegations under the civil False Claims Act case and is the largest civil fraud settlement against a pharmaceutical company. Six whistle-blowers were awarded more than $102 million for their role in the investigation.[14] Former Pfizer sales representative John Kopchinski acted as a qui tam relator and filed a complaint in 2004 outlining the illegal conduct in the marketing of Bextra.[15] Kopchinski was awarded $51.5 million for his role in the case because the improper marketing of Bextra was the largest piece of the settlement at $1.8 billion.[16]

Assay of valdecoxib

Several HPLC-UV methods[17] have been reported for valdecoxib estimation in biological samples like human urine.[18][19] Valdecoxib has analytical methods for bioequivalence studies,[20][21] metabolite determination,[22][23][18] estimation of formulation,[24] and an HPTLC method for simultaneous estimation in tablet dosage form.[25]

References

- Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 52X. ISBN 9783527607495.

- "Pfizer fined $2.3B in record fraud settlement Pharma giant illegally promoted product: Justice Department says, in largest health care fraud settlement in history". Washington: CNN. 2 September 2009. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- Gardiner H (2 September 2009). "Pfizer Pays $2.3 Billion to Settle Marketing Case". New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- "Valdecoxib. U.S. FDA Drug Approval". Thomson Micromedex. Retrieved June 8, 2007.

- "Information for Healthcare Professionals: Valdecoxib (marketed as Bextra)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2005. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- Elkind P, Reingold J (28 July 2011). "Inside Pfizer's palace coup". Fortune. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- "Pfizer to pay $2.3 billion to resolve criminal and civil health care liability relating to fraudulent marketing and the payment of kickbacks". Stop Medicare Fraud, US Dept of Health & Human Svc, and of Justice. Archived from the original on 2012-08-30. Retrieved 2012-07-04.

- Zhang J, Ding EL, Song Y (October 2006). "Adverse effects of cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors on renal and arrhythmia events: meta-analysis of randomized trials". JAMA. 296 (13): 1619–32. doi:10.1001/jama.296.13.jrv60015. PMID 16968832.

- "Pfizer agrees record fraud fine", BBC, 2009-09-02

- "Pharmacia & Upjohn Company Inc Pleads Guilty to Fraudulent Marketing of Bextra". Archived from the original on 2009-12-07. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- "The United States Department of Justice - United States Attorney's Office - District of Massachusetts". Archived from the original on 2009-06-01. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- Edwards J (2009-06-26). "Pfizer's Off-Label Bextra Team Was Called "The Highlanders" - CBS News". Industry.bnet.com. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- "The United States Department of Justice - United States Attorney's Office - District of Massachusetts". Archived from the original on 2009-09-01. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- "Federal Bureau of Investigation - Press Release". Archived from the original on 2010-09-09. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- "Whistleblower News | Articles, Blogs, & Insights | Phillips & Cohen". Phillipsandcohen.com. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- "Whistleblower news | Phillips & Cohen LLP". Phillipsandcohen.com. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- Prafulla Kumar Sahu and M. Mathrusri Annapurna, Analytical method development by liquid chromatography, LAP Lambert Academic Publisher, Germany, 2011 ISBN 3-8443-2869-6.

- Zhang JY, Fast DM, Breau AP (February 2003). "Determination of valdecoxib and its metabolites in human urine by automated solid-phase extraction-liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry". Journal of Chromatography. B, Analytical Technologies in the Biomedical and Life Sciences. 785 (1): 123–34. doi:10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00863-2. PMID 12535845.

- Sane RT, Menon S, Deshpande AY, Jain A (February 2005). "HPLC determination and pharmacokinetic study of valdecoxib in human plasma". Chromatographia. 61 (3–4): 137–41. doi:10.1365/s10337-004-0442-2. S2CID 95275785.

- Sahu PK, Sankar KR, Annapurna MM (2011). "Determination of Valdecoxib in Human Plasma Using Reverse Phase HPLC". Journal of Chemistry. 8 (2): 875–81.

- Mandal U, Jayakumar M, Ganesan M, Nandi S, Pal TK, Chakraborty MK, Roy Chowdhary A, Chattoraj TK (2004). "[title]". Indian Drugs. 41: 59.

- Zhang JY, Fast DM, Breau AP (September 2003). "Development and validation of an automated SPE-LC-MS/MS assay for valdecoxib and its hydroxylated metabolite in human plasma". Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 33 (1): 61–72. doi:10.1016/s0731-7085(03)00349-2. PMID 12946532.

- Werner U, Werner D, Hinz B, Lambrecht C, Brune K (March 2005). "A liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry method for the quantification of both etoricoxib and valdecoxib in human plasma". Biomedical Chromatography. 19 (2): 113–8. doi:10.1002/bmc.423. PMID 15473012.

- Sutariya VB, Rajashree M, Sankalia MG, Priti P (2004). "[title]". Indian J Pharm Sci. 93: 112.

- Gandhimathi M, Ravi TK, Shukla N, Sowmiya G (January 2007). "High Performance Thin Layer Chromatographic Method for Simultaneous Estimation of Paracetamol and Valdecoxib in Tablet Dosage Form". Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 69 (1): 145. doi:10.4103/0250-474X.32133.