Demeclocycline

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Declomycin |

| Other names | Demeclocycline hydrochloride, RP-10192 |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Tetracycline antibiotic[1] |

| Main uses | Bacterial infections, SIADH[2] |

| Side effects | Nausea, rash, kidney problems, allergic reactions[1] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682103 |

| Legal | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 60–80% |

| Protein binding | 41–50% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 10–17 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Chemical and physical data | |

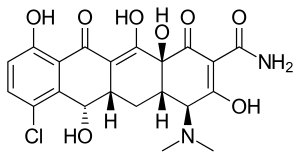

| Formula | C21H21ClN2O8 |

| Molar mass | 464.86 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Demeclocycline, sold under the brand names Declomycin among others, is a tetracycline antibiotic used to treat a number of bacterial infections as well as low sodium due to syndrome of inappropriate ADH (SIADH).[2] These infections include pneumonia, acne, chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis.[1] It is taken by my mouth.[2]

Common side effects include nausea, rash, kidney problems, and allergic reactions.[1] Other side effects may include diabetes insipidus and a feeling of the world spinning.[1] Use in pregnancy may harm the baby and use in children under 8 not generally recommended.[1] Other side effects may include sunburns.[2]

Demeclocycline has been approved for medical use in the United States since at least 1960.[1] It is available as a generic medication.[2] In the United Kingdom 28 tablets of 150 mg costs the NHS about £220 as of 2021.[2] In the United States this amount is about 70 USD.[3] It is made from Streptomyces aureofaciens.[1]

Medical uses

Infections

Demeclocycline is used to treat various types of bacterial infections.[4] It is used as an antibiotic in the treatment of Lyme disease,[5] acne,[6] and bronchitis.[7] Resistance, though, is gradually becoming more common,[8] and demeclocycline is now rarely used for treatment of infections.[9][10]

Low sodium

It is used (though off-label in many countries including the United States) in the treatment of hyponatremia (low blood sodium concentration) due to the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) when fluid restriction alone has been ineffective.[11] Physiologically, this works by reducing the responsiveness of the collecting tubule cells to ADH.[12]

The use in SIADH actually relies on a side effect; demeclocycline induces nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (dehydration due to the inability to concentrate urine).[11][13][14]

The use of demeclocycline in SIADH was first reported in 1975,[15] and, in 1978, a larger study found it to be more effective and better tolerated than lithium carbonate, the only available treatment at the time.[16] Demeclocycline used to be the drug of choice for treating SIADH.[14] Meanwhile it might be superseded, now that vasopressin receptor antagonists, such as tolvaptan, became available.[16]

Dosage

For infections it may be used at 300 mg twice per day while for SIADH it may be used at doses of 300 mg three times per day.[2]

Contraindications

Like other tetracyclines, demeclocycline is contraindicated in children and pregnant or nursing women. All members of this class interfere with bone development and may discolour teeth.[10]

Side effects

These are similar to those of other tetracyclines. Skin reactions with sunlight have been reported.[16] Like only few other known tetracycline derivatives, demeclocycline causes nephrogenic diabetes insipidus.[17] Furthermore demeclocycline might have psychotropic side effects similar to lithium.[18]

Tetracyclines bind to cations, such as calcium, iron (when given orally), and magnesium, rendering them insoluble and inadsorbable for the gastrointestinal tract. Demeclocycline should not be taken with food (particularly milk and other dairy products) or antacids.[10]

Mechanism of action

As with related tetracycline antibiotics, demeclocycline acts by binding to the 30S ribosomal subunit to inhibit binding of aminoacyl tRNA which impairs protein synthesis by bacteria. It is bacteriostatic (it impairs bacterial growth, but does not kill bacteria directly).[19][8]

Demeclocycline inhibits the renal action of antidiuretic hormone by interfering with the intracellular second messenger cascade (specifically, inhibiting adenylyl cyclase activation) after the hormone binds to vasopressin V2 receptors in the kidney.[20][21][22] Exactly how demeclocycline does this has yet to be elucidated, however.[22]

Society and culture

Brand names

Declomycin, Declostatin, Ledermycin, Bioterciclin, Deganol, Deteclo, Detravis, Meciclin, Mexocine, and Clortetrin.

Manufacture

It was derived from a mutant strain of Streptomyces aureofaciens.[19][23]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Demeclocycline Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 BNF 81: March-September 2021. BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. 2021. p. 601. ISBN 978-0857114105.

- ↑ "Demeclocycline Prices, Coupons & Savings Tips - GoodRx". GoodRx. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ↑ DailyMed. "Demeclocycline Hydrochloride - demeclocycline tablet". Drug label information. Archived from the original on 2018-10-12. Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- ↑ Rosner, Bryan (2007). The Top 10 Lyme Disease Treatments: Defeat Lyme Disease with the Best of Conventional and Alternative Medicine. pp. 84, 86. ISBN 9780976379713. Archived from the original on 2020-08-01. Retrieved 2021-07-27.

- ↑ Ad Hoc Committee on the Use of Antibiotics in Dermatology (1975). "Systemic antibiotics for treatment of acne vulgaris: efficacy and safety". Arch. Dermatol. 111 (12): 1630–1636. doi:10.1001/archderm.1975.01630240086015. PMID 128326.

- ↑ Beatson, J. M.; Marsh, B. T.; Talbot, D. J. (1985). "A clinical comparison of pivmecillinam plus pivampicillin (Miraxid) and a triple tetracycline combination (Deteclo) in respiratory infections treated in general practice". J. Int. Med. Res. 13 (4): 197–202. doi:10.1177/030006058501300401. PMID 3930309. S2CID 23485353.

- 1 2 Schnappinger, Dirk; Hillen, Wolfgang (July 1996). "Tetracyclines: Antibiotic action, uptake, and resistance mechanisms". Archives of Microbiology. 165 (6): 359–369. doi:10.1007/s002030050339. PMID 8661929. S2CID 6199423.

- ↑ Klein, Natalie C.; Cunha, Burke A. (1995). "Tetracyclines". Medical Clinics of North America. 79 (4): 789–801. doi:10.1016/S0025-7125(16)30039-6. PMID 7791423.

- 1 2 3 Lexi-Comp (August 2008). "Demeclocycline". The Merck Manual Professional. Archived from the original on 2010-08-17. Retrieved 2021-07-27. Retrieved on October 27, 2008.

- 1 2 Goh KP (May 2004). "Management of hyponatremia". American Family Physician. 69 (10): 2387–94. PMID 15168958. Archived from the original on 2008-10-16. Retrieved 2021-07-27.

- ↑ Kortenoeven, M. L.; Sinke, A. P.; Hadrup, N.; Trimpert, C.; Wetzels, J. F.; Fenton, R. A.; Deen, P. M. (2013). "Demeclocycline attenuates hyponatremia by reducing aquaporin-2 expression in the renal inner medulla". Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 305 (12): F1705–F1718. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00723.2012. PMID 24154696.

- ↑ Hayek, Alberto; Ramirez, Jimeno (1974). "Demeclocycline-induced diabetes insipidus". JAMA. 229 (6): 676–677. doi:10.1001/jama.1974.03230440034026. PMID 4277429.

- 1 2 Miell, J.; Dhanjal, P.; Jamookeeah, C. (2015). "Evidence for the use of demeclocycline in the treatment of hyponatraemia secondary to SIADH: a systematic review". Int. J. Clin. Pract. 69 (12): 1396–1417. doi:10.1111/ijcp.12713. PMC 5042094. PMID 26289137.

- ↑ Cherrill DA, Stote RM, Birge JR, Singer I (November 1975). "Demeclocycline treatment in the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion". Annals of Internal Medicine. 83 (5): 654–6. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-83-5-654. PMID 173218.

- 1 2 3 Tolstoi LG (2002). "A brief review of drug-induced syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone". Medscape Pharmacotherapy. 4 (1). Archived from the original on June 6, 2013.

- ↑ Cox, Malcolm (1982). "Tetracycline Nephrotoxicity". In Porter, George A. (ed.). Nephrotoxic Mechanisms of Drugs and Environmental Toxins. Boston, MA: Springer. pp. 165–177. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-4214-4_15. ISBN 978-1-4684-4216-8. Archived from the original on 2020-08-01. Retrieved 2021-07-27.

- ↑ Mørk, A.; Geisler, A. (1995). "A comparative study on the effects of tetracyclines and lithium on the cyclic AMP second messenger system". Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 19 (1): 157–169. doi:10.1016/0278-5846(94)00112-U. PMID 7708928. S2CID 36219362.

- 1 2 Chopra, I.; Hawkey, P. M.; Hinton, M. (1992). "Tetracyclines, molecular and clinical aspects". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 29 (3): 245–277. doi:10.1093/jac/29.3.245. PMID 1592696.

- ↑ Eric Fliers; Marta Korbonits; J.A. Romijn (28 August 2014). Clinical Neuroendocrinology. Elsevier Science. pp. 43–. ISBN 978-0-444-62612-7. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ↑ L. Kovács; B. Lichardus (6 December 2012). Vasopressin: Disturbed Secretion and Its Effects. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 180–. ISBN 978-94-009-0449-1. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- 1 2 Ajay K. Singh; Gordon H. Williams (12 January 2009). Textbook of Nephro-Endocrinology. Academic Press. pp. 251–. ISBN 978-0-08-092046-7. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ↑ J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 356–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|