Retinoid

The retinoids are a class of chemical compounds that are vitamers of vitamin A or are chemically related to it. Retinoids have found use in medicine where they regulate epithelial cell growth.

Retinoids have many important functions throughout the body including roles in vision,[1] regulation of cell proliferation and differentiation, growth of bone tissue, immune function, and activation of tumor suppressor genes.

Research is also being done into their ability to treat skin cancers. Currently, alitretinoin (9-cis-retinoic acid) may be used topically to help treat skin lesions from Kaposi's sarcoma, and tretinoin (all-trans- retinoic acid) is used to treat acute promyelocytic leukemia.

Types

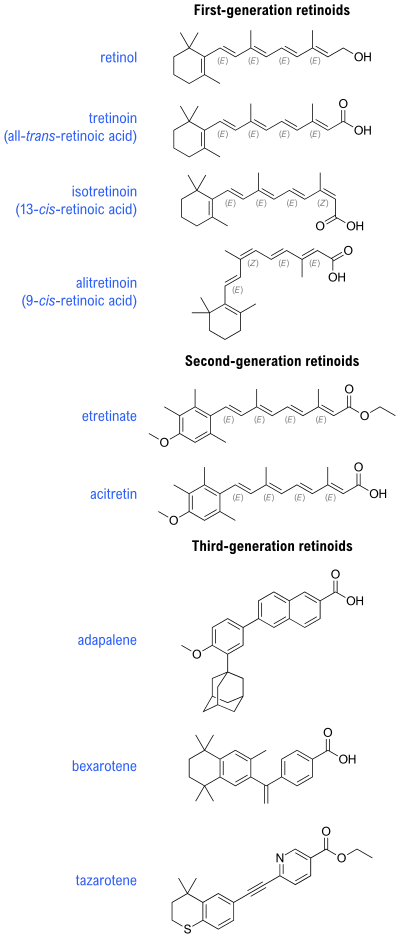

There are four generations of retinoids:

- First generation include retinol, retinal, tretinoin (retinoic acid), isotretinoin, and alitretinoin

- Second generation include etretinate and its metabolite acitretin

- Third generation include adapalene, bexarotene, and tazarotene

- Fourth generation includes Trifarotene

Some authors consider retinoids derived from pyranones as the fourth-generation. One such compound is seletinoid G.[2]

Structure

The basic structure of the hydrophobic retinoid molecule consists of a cyclic end group, a polyene side chain and a polar end group. The conjugated system formed by alternating C=C double bonds in the polyene side chain are responsible for the color of retinoids (typically yellow, orange, or red). Hence, many retinoids are chromophores. Alternation of side chains and end groups creates the various classes of retinoids.

First- and second-generation retinoids are able to bind with several retinoid receptors due to the flexibility imparted by their alternating single and double bonds.

Third-generation retinoids are less flexible than first- and second-generation retinoids and therefore, interact with fewer retinoid receptors.

Fourth-generation retinoid, Trifarotene, binds selectively to the RAR-y receptor. It was approved for use in the US in 2019.

Absorption

The major source of retinoids from the diet are plant pigments such as carotenes and retinyl esters derived from animal sources. Retinyl esters are hydrolyzed in the intestinal lumen to yield free retinol and the corresponding fatty acid (i.e. palmitate or stearate). After hydrolysis, retinol is taken up by the enterocytes. Retinyl ester hydrolysis requires the presence of bile salts that serve to solubilize the retinyl esters in mixed micelles and to activate the hydrolyzing enzymes [3]

Several enzymes that are present in the intestinal lumen may be involved in the hydrolysis of dietary retinyl esters. Cholesterol esterase is secreted into the intestinal lumen from the pancreas and has been shown, in vitro, to display retinyl ester hydrolase activity. In addition, a retinyl ester hydrolase that is intrinsic to the brush-border membrane of the small intestine has been characterized in the rat as well as in the human. The different hydrolyzing enzymes are activated by different types of bile salts and have distinct substrate specificities. For example, whereas the pancreatic esterase is selective for short-chain retinyl esters, the brush-border membrane enzyme preferentially hydrolyzes retinyl esters containing a long-chain fatty acid such as palmitate or stearate. Retinol enters the absorptive cells of the small intestine, preferentially in the all-trans-retinol form.

Uses

Retinoids are used in the treatment of many diverse diseases and are effective in the treatment of a number of dermatological conditions such as inflammatory skin disorders, skin cancers, disorders of increased cell turnover (e.g. psoriasis),[4] photoaging,[5] and skin wrinkles.[6]

Common skin conditions treated by retinoids include acne and psoriasis.[7]

Isotretinoin is not only considered the only known possible cure of acne in some patients, but was originally a chemotherapy treatment for certain cancers, such as leukemia.

Human embryonic stem cells also more readily differentiate into cortical stem cells in the presence of retinoids[8]

Retinoids are known to reduce the risk of head and neck cancers.[9][10]

Synthesis

Retinoids can be synthesized in a variety of ways. A common procedure to lower retinoid toxicity and improve retinoid activity is glucuronidation. Walker et al. have proposed a novel synthesis to accomplish glucuronidation.[11]

Side effects

.jpg.webp)

Toxic effects occur with prolonged high intake. The specific toxicity is related to exposure time and the exposure concentration. A medical sign of chronic poisoning is the presence of painful tender swellings on the long bones. Anorexia, skin lesions, hair loss, hepatosplenomegaly, papilloedema, bleeding, general malaise, pseudotumor cerebri, and death may also occur.

Chronic overdose also causes an increased lability of biological membranes and of the outer layer of the skin to peel.[12]

Recent research has suggested a role for retinoids in cutaneous adverse effects for a variety of drugs including the antimalarial drug proguanil. It is proposed that drugs such as proguanil act to disrupt retinoid homeostasis.

Systemic retinoids (isotretinoin, etretinate) are contraindicated during pregnancy as they may cause CNS, cranio-facial, cardiovascular and other defects.

See also

- Adapalene

- Hypervitaminosis A syndrome

- Biotinylated retinoids

References

- ↑ Kiser, Philip D.; Golczak, Marcin; Palczewski, Krzysztof (11 July 2013). "Chemistry of the Retinoid (Visual) Cycle". Chemical Reviews. 114 (1): 194–232. doi:10.1021/cr400107q. PMC 3858459. PMID 23905688.

- ↑ Mukherjee, S; Date, A; Patravale, V; Korting, HC; Roeder, A; Weindl, G (2006). "Retinoids in the treatment of skin aging: an overview of clinical efficacy and safety". Clinical Interventions in Aging. 1 (4): 327–48. doi:10.2147/ciia.2006.1.4.327. PMC 2699641. PMID 18046911.

- ↑ Noy, N. (2006) "Vitamin A", "Biochemical, Physiological, & Molecular Aspects of Human Nutrition", M. H. Stipanuk 2nd Ed.

- ↑ "Psoriasis - Diagnosis and treatment - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Archived from the original on 7 May 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ↑ Stefanaki C, Stratigos A, Katsambas A (June 2005). "Topical retinoids in the treatment of photoaging". J Cosmet Dermatol. 4 (2): 130–4. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2165.2005.40215.x. PMID 17166212. S2CID 44702740.

- ↑ Kafi, R; Kwak, HS; Schumacher, WE; Cho, S; Hanft, VN; Hamilton, TA; King, AL; Neal, JD; Varani, J; Fisher, GJ; Voorhees, JJ; Kang, S (2007). "Improvement of naturally aged skin with vitamin A (retinol)". Arch Dermatol. 143 (5): 606–12. doi:10.1001/archderm.143.5.606. PMID 17515510.

- ↑ "National Psoriasis Foundation". psoriasis.org. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ↑ http://www.nature.com/neuro/journal/vaop/ncurrent/fig_tab/nn.3041_F1.html Archived November 5, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Smith, W; Saba, N (2005). "Retinoids as chemoprevention for head and neck cancer: Where do we go from here?". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 55 (2): 143–52. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2005.02.003. PMID 15886010.

- ↑ 2009 Internal Medicine Boards-Style Q&A Archived 2012-09-19 at the Wayback Machine, Q:378, p.232; A:378, p.125

- ↑ Walker, JR; Alshafie, G; Abou-Issa, H; Curley, RW (12 September 2002). "An Improved Synthesis of the C-linked Glucuronide of N-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)retinamide". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 12 (17): 2447–50. doi:10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00427-4. PMID 12161154.

- ↑ "Topical retinoids - DermNet New Zealand". dermnetnz.org. Archived from the original on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 10th Edition, Goodman & Gilman.

- Clinical Pharmacology, P.N. Bennett & M.J. Brown.

External links

- Retinoids at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)