Salicylic acid

| |||

| |||

| Clinical data | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ | ||

| Chemical and physical data | |||

| Formula | C7H6O3 | ||

| Molar mass | 138.122 g·mol−1 | ||

| 3D model (JSmol) | |||

| Density | 1.443 g/cm3 (20 °C)[1] g/cm3 | ||

| Boiling point | decomposes[2] 211 °C (412 °F; 484 K) at 20 mmHg[1] | ||

| Solubility in water | mg/mL (20 °C) | ||

SMILES

| |||

InChI

| |||

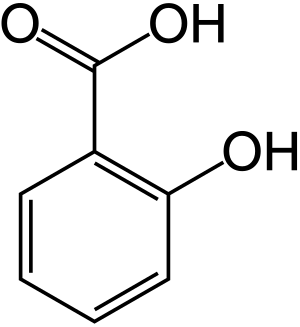

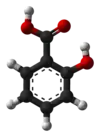

Salicylic acid is an organic compound with the formula HOC6H4CO2H. A colorless solid, it is a precursor to and a metabolite of aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid). It is a plant hormone.[4] The name is from Latin salix for willow tree. It is an ingredient in some anti-acne products. Salts and esters of salicylic acid are known as salicylates.

Uses

Medicine

Salicylic acid as a medication is used commonly to remove the outer layer of the skin. As such, it is used to treat warts, psoriasis, acne vulgaris, ringworm, dandruff, and ichthyosis.[5][6][7][8]

Similar to other hydroxy acids, salicylic acid is an ingredient in many skincare products for the treatment of seborrhoeic dermatitis, acne, psoriasis, calluses, corns, keratosis pilaris, acanthosis nigricans, ichthyosis, and warts.[9]

Uses in manufacturing

Salicylic acid is used in the production of other pharmaceuticals, including 4-aminosalicylic acid, sandulpiride, and landetimide (via salethamide).

Salicylic acid has long been a key starting material for making acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin).[4] Aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid or ASA) is prepared by the esterification of the phenolic hydroxyl group of salicylic acid with the acetyl group from acetic anhydride or acetyl chloride.

Bismuth subsalicylate, a salt of bismuth and salicylic acid, is the active ingredient in stomach-relief aids such as Pepto-Bismol, is the main ingredient of Kaopectate, and "displays anti-inflammatory action (due to salicylic acid) and also acts as an antacid and mild antibiotic".[10]

Other derivatives include methyl salicylate used as a liniment to soothe joint and muscle pain and choline salicylate used topically to relieve the pain of mouth ulcers.

Other uses

Salicylic acid is used as a food preservative, a bactericide, and an antiseptic.[11]

Sodium salicylate is a useful phosphor in the vacuum ultraviolet spectral range, with nearly flat quantum efficiency for wavelengths between 10 and 100 nm.[12] It fluoresces in the blue at 420 nm. It is easily prepared on a clean surface by spraying a saturated solution of the salt in methanol followed by evaporation.

Mechanism of action

Salicylic acid modulates COX1 enzymatic activity to decrease the formation of pro-inflammatory prostaglandins. Salicylate may competitively inhibit prostaglandin formation. Salicylate's antirheumatic (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory) actions are a result of its analgesic and anti-inflammatory mechanisms.

Salicylic acid works by causing the cells of the epidermis to slough off more readily, preventing pores from clogging up, and allowing room for new cell growth. Salicylic acid inhibits the oxidation of uridine-5-diphosphoglucose (UDPG) competitively with nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide and noncompetitively with UDPG. It also competitively inhibits the transferring of glucuronyl group of uridine-5-phosphoglucuronic acid to the phenolic acceptor.

The wound-healing retardation action of salicylates is probably due mainly to its inhibitory action on mucopolysaccharide synthesis.[13]

Safety

If high concentrations of salicylic ointment are applied to a large percentage of body surface, high levels of salicylic acid can enter the blood, requiring hemodialysis to avoid further complications.[14]

Production and chemical reactions

Biosynthesis

Salicylic acid is biosynthesized from the amino acid phenylalanine. In Arabidopsis thaliana, it can be synthesized via a phenylalanine-independent pathway.

Industrial synthesis

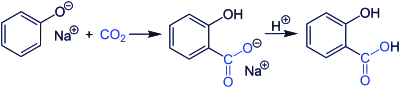

Sodium salicylate is commercially prepared by treating sodium phenolate (the sodium salt of phenol) with carbon dioxide at high pressure (100 atm) and high temperature (115 °C) – a method known as the Kolbe-Schmitt reaction. Acidification of the product with sulfuric acid gives salicylic acid:

It can also be prepared by the hydrolysis of aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid)[15] or methyl salicylate (oil of wintergreen) with a strong acid or base.

Reactions

Upon heating, salicylic acid converts to phenyl salicylate:[16][4]

- 2 HOC6H4CO2H → C6H5O2C6H4OH + CO2 + H2O

Further heating gives xanthone.[4]

Salicylic acid as its conjugate base is a chelating agent, with an affinity for iron(III).[17]

Salicylic acid slowly degrades to phenol and carbon dioxide at 200–230 °C:[18]

- C6H4OH(CO2H) → C6H5OH + CO2

History

Hippocrates, Galen, Pliny the Elder, and others knew that willow bark could ease pain and reduce fevers.[19] It was used in Europe and China to treat these conditions.[20] This remedy is mentioned in texts from Ancient Egypt, Sumer, and Assyria.[21] The Cherokee and other Native Americans use an infusion of the bark for fever and other medicinal purposes.[22]

In 2014, archaeologists identified traces of salicylic acid on seventh-century pottery fragments found in east-central Colorado.[23] The Reverend Edward Stone, a vicar from Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire, England, noted in 1763 that the bark of the willow was effective in reducing a fever.[24]

The active extract of the bark, called salicin, after the Latin name for the white willow (Salix alba), was isolated and named by German chemist Johann Andreas Buchner in 1828.[25] A larger amount of the substance was isolated in 1829 by Henri Leroux, a French pharmacist.[26] Raffaele Piria, an Italian chemist, was able to convert the substance into a sugar and a second component, which on oxidation becomes salicylic acid.[27][28]

Salicylic acid was also isolated from the herb meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria, formerly classified as Spiraea ulmaria) by German researchers in 1839.[29] While their extract was somewhat effective, it also caused digestive problems such as gastric irritation, bleeding, diarrhea, and even death when consumed in high doses.

Dietary sources

Salicylic acid occurs in plants as free salicylic acid and its carboxylated esters and phenolic glycosides. Several studies suggest that humans metabolize salicylic acid in measurable quantities from these plants.[30] High-salicylate beverages and foods include beer, coffee, tea, numerous fruits and vegetables, sweet potato, nuts, and olive oil.[31] Meat, poultry, fish, eggs, dairy products, sugar, and breads and cereals have low salicylate content.[31][32]

Some people with sensitivity to dietary salicylates may have symptoms of allergic reaction, such as bronchial asthma, rhinitis, gastrointestinal disorders, or diarrhea, so may need to adopt a low-salicylate diet.[31]

Plant hormone

Salicylic acid is a phenolic phytohormone, and is found in plants with roles in plant growth and development, photosynthesis, transpiration, and ion uptake and transport.[33] Salicylic acid is involved in endogenous signaling, mediating plant defense against pathogens.[34] It plays a role in the resistance to pathogens (i.e. systemic acquired resistance) by inducing the production of pathogenesis-related proteins and other defensive metabolites.[35] Exogenously, salicylic acid can aid plant development via enhanced seed germination, bud flowering, and fruit ripening, though too high of a concentration of salicylic acid can negatively regulate these developmental processes.[36]

The volatile methyl ester of salicylic acid, methyl salicylate, can also diffuse through the air, facilitating plant-plant communication.[37] Methyl salicylate is taken up by the stomata of the nearby plant, where it can induce an immune response after being converted back to salicylic acid.[38]

Signal transduction

A number of proteins have been identified that interact with SA in plants, especially salicylic acid binding proteins (SABPs) and the NPR genes (Nonexpressor of pathogenesis related genes), which are putative receptors.[39]

History

In 1979, salicylates were found to be involved in induced defenses of tobacco against tobacco mosaic virus.[40] In 1987, salicylic acid was identified as the long-sought signal that causes thermogenic plants such as the voodoo lily, Sauromatum guttatum, to heat up.[41]

See also

References

- 1 2 Haynes, William M., ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 3.306. ISBN 1439855110.

- 1 2 "Salicylic acid". Archived from the original on 2014-05-24. Retrieved 2014-05-23.

- ↑ Atherton Seidell; William F. Linke (1952). Solubilities of Inorganic and Organic Compounds: A Compilation of Solubility Data from the Periodical Literature. Supplement. Van Nostrand. Archived from the original on 2020-03-11. Retrieved 2021-07-31.

- 1 2 3 4 Boullard, Olivier; Leblanc, Henri; Besson, Bernard (2000). "Salicylic Acid". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a23_477. ISBN 3527306730.

- ↑ "Salicylic acid". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. p. 310. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- ↑ "SALICYLIC ACID - National Library of Medicine HSDB Database". toxnet.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2018-08-21. Retrieved 2018-08-21.

- ↑ salicylic acid 17 % Topical Liquid Archived 2021-08-29 at the Wayback Machine. Kaiser Permanente Drug Encyclopedia. Accessed 28 Sept 2011.

- ↑ Madan RK; Levitt J (April 2014). "A review of toxicity from topical salicylic acid preparations". J Am Acad Dermatol. 70 (4): 788–92. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.12.005. PMID 24472429.

- ↑ "Bismuth subsalicylate". PubChem. United States National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ↑ "Definition of Salicylic acid". MedicineNet.com. Archived from the original on 2011-12-09. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

- ↑ Samson, James (1976). Techniques of Vacuum Ultraviolet Spectroscopy. Wiley, .

- ↑

- ↑ Péc, J.; Strmenová, M.; Palencárová, E.; Pullmann, R.; Funiaková, S.; Visnovský, P.; Buchanec, J.; Lazarová, Z. (October 1992). "Salicylate intoxication after use of topical salicylic acid ointment by a patient with psoriasis". Cutis. 50 (4): 307–309. ISSN 0011-4162. PMID 1424799.

- ↑ "Hydrolysis of ASA to SA". Archived from the original on August 8, 2007. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- ↑ Kuriakose, G.; Nagaraju, N. (2004). "Selective Synthesis of Phenyl Salicylate (Salol) by Esterification Reaction over Solid Acid Catalysts". Journal of Molecular Catalysis A: Chemical. 223 (1–2): 155–159. doi:10.1016/j.molcata.2004.03.057.

- ↑ Jordan, R. B. (1983). "Metal(III)-Salicylate Complexes: Protonated Species and Rate-Controlling Formation Steps". Inorganic Chemistry. 22 (26): 4160–4161. doi:10.1021/ic00168a070.

- ↑ Kaeding, Warren W. (1 September 1964). "Oxidation of Aromatic Acids. IV. Decarboxylation of Salicylic Acids". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 29 (9): 2556–2559. doi:10.1021/jo01032a016.

- ↑ Norn, S.; Permin, H.; Kruse, P. R.; Kruse, E. (2009). "[From willow bark to acetylsalicylic acid]". Dansk Medicinhistorisk Årbog (in dansk). 37: 79–98. PMID 20509453.

- ↑ "Willow bark". University of Maryland Medical Center. University of Maryland. Archived from the original on 24 December 2011. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ↑ Goldberg, Daniel R. (Summer 2009). "Aspirin: Turn of the Century Miracle Drug". Chemical Heritage Magazine. 27 (2): 26–30. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ↑ Hemel, Paul B. and Chiltoskey, Mary U. Cherokee Plants and Their Uses – A 400 Year History, Sylva, NC: Herald Publishing Co. (1975); cited in Dan Moerman, A Database of Foods, Drugs, Dyes and Fibers of Native American Peoples, Derived from Plants. Archived 2007-12-06 at the Wayback Machine A search of this database for "salix AND medicine" finds 63 entries.

- ↑ "1,300-Year-Old Pottery Found in Colorado Contains Ancient 'Natural Aspirin'". Archived from the original on 2014-08-13. Retrieved 2014-08-13.

- ↑ Stone, Edmund (1763). "An Account of the Success of the Bark of the Willow in the Cure of Agues". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 53: 195–200. doi:10.1098/rstl.1763.0033. Archived from the original on 2022-01-11. Retrieved 2021-07-31.

- ↑ Buchner, A. (1828). "Ueber das Rigatellische Fiebermittel und über eine in der Weidenrinde entdeckte alcaloidische Substanz (On Rigatelli's antipyretic [i.e., anti-fever drug] and on an alkaloid substance discovered in willow bark)". Repertorium für die pharmacie…. Bei J. L. Schrag. pp. 405–. Archived from the original on 2020-08-19. Retrieved 2021-07-31.

Noch ist es mir aber nicht geglückt, den bittern Bestandtheil der Weide, den ich Salicin nennen will, ganz frei von allem Färbestoff darzustellen." (I have still not succeeded in preparing the bitter component of willow, which I will name salicin, completely free from colored matter

- ↑ See:

- Leroux, H. (1830). "Mémoire relatif à l'analyse de l'écorce de saule et à la découverte d'un principe immédiat propre à remplacer le sulfate de quinine"] (Memoir concerning the analysis of willow bark and the discovery of a substance immediately likely to replace quinine sulfate)". Journal de Chimie Médicale, de Pharmacie et de Toxicologie. 6: 340–342. Archived from the original on 2017-03-24. Retrieved 2021-07-31.

- A report on Leroux's presentation to the French Academy of Sciences also appeared in: Mémoires de l'Académie des sciences de l'Institut de France. Institut de France. 1838. pp. 20–. Archived from the original on 2022-09-03. Retrieved 2021-07-31.

- ↑ Piria (1838) "Sur de neuveaux produits extraits de la salicine" Archived 2017-07-27 at the Wayback Machine (On new products extracted from salicine), Comptes rendus … 6: 620–624. On page 622, Piria mentions "Hydrure de salicyle" (hydrogen salicylate, i.e., salicylic acid).

- ↑ Jeffreys, Diarmuid (2005). Aspirin: the remarkable story of a wonder drug. New York: Bloomsbury. pp. 38–40. ISBN 978-1-58234-600-7. Archived from the original on 2020-09-15. Retrieved 2021-07-31.

- ↑ Löwig, C.; Weidmann, S. (1839). "III. Untersuchungen mit dem destillierten Wasser der Blüthen von Spiraea Ulmaria (III. Investigations of the water distilled from the blossoms of Spiraea ulmaria). Löwig and Weidman called salicylic acid Spiräasaure (spiraea acid)". Annalen der Physik und Chemie; Beiträge zur Organischen Chemie (Contributions to Organic Chemistry) (46): 57–83. Archived from the original on 2022-03-13. Retrieved 2021-07-31.

- ↑ Malakar, Sreepurna; Gibson, Peter R.; Barrett, Jacqueline S.; Muir, Jane G. (1 April 2017). "Naturally occurring dietary salicylates: A closer look at common Australian foods". Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 57: 31–39. doi:10.1016/j.jfca.2016.12.008.

- 1 2 3 "Low salicylate diet". Drugs.com. 19 February 2019. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ↑ Swain, AR; Dutton, SP; Truswell, AS (1985). "Salicylates in foods" (PDF). Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 85 (8): 950–60. ISSN 0002-8223. PMID 4019987. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-04-05. Retrieved 2019-12-16.

- ↑ Vlot, A. C; Dempsey, D. A; Klessig, D. F (2009). "Salicylic Acid, a multifaceted hormone to combat disease". Annual Review of Phytopathology. 47: 177–206. doi:10.1146/annurev.phyto.050908.135202. PMID 19400653.

- ↑ Hayat, S. & Ahmad, A. (2007). Salicylic Acid – A Plant Hormone. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-5183-8.

- ↑ Van Huijsduijnen, R. A. M. H.; Alblas, S. W.; De Rijk, R. H.; Bol, J. F. (1986). "Induction by Salicylic Acid of Pathogenesis-related Proteins or Resistance to Alfalfa Mosaic Virus Infection in Various Plant Species". Journal of General Virology. 67 (10): 2135–2143. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-67-10-2135.

- ↑ Koo, Young Mo; Heo, A Yeong; Choi, Hyong Woo (February 2020). "Salicylic Acid as a Safe Plant Protector and Growth Regulator". The Plant Pathology Journal. 36 (1): 1–10. doi:10.5423/PPJ.RW.12.2019.0295. ISSN 1598-2254. PMC 7012573. PMID 32089657.

- ↑ Taiz, L. and Zeiger, Eduardo (2002) Plant Physiology Archived 2014-03-05 at the Wayback Machine, 3rd Edition, Sinauer Associates, p. 306, ISBN 0878938230

- ↑ Chamowitz, D. (2017). What a plant knows: a field guide to the senses. Brunswick, Vic.: Scribe Publications.

- ↑ Kumar, D. 2014. Salicylic acid signaling in disease resistance. Plant Science 228:127–134.

- ↑ Raskin, I. 1992. Salicylate, A New Plant Hormone. Plant Physiol 99:799–803.

- ↑ Raskin, I., A. Ehmann, W. R. Melander, and B. J. Meeuse. 1987. Salicylic Acid: a natural inducer of heat production in arum lilies. Science 237:1601–1602.

Further reading

- Schrör, Karsten (2016). Acetylsalicylic Acid (2 ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 9–10. ISBN 9783527685028. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2021-07-31.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|

- Salicylic acid MS Spectrum Archived 2021-04-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Safety MSDS data Archived 2009-02-03 at the Wayback Machine

- International Chemical Safety Cards | CDC/NIOSH Archived 2017-10-25 at the Wayback Machine

- "On the syntheses of salicylic acid" Archived 2020-08-06 at the Wayback Machine: English Translation of Hermann Kolbe's seminal 1860 German article "Ueber Synthese der Salicylsäure" in Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie at MJLPHD Archived 2020-10-18 at the Wayback Machine