Lisdexamfetamine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Tyvense, Elvanse, Vyvanse, others |

| Other names | (2S)-2,6-Diamino-N-[(2S)-1-phenylpropan-2-yl]hexanamide N-[(2S)-1-Phenyl-2-propanyl]-L-lysinamide |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Central nervous system (CNS) stimulant[1][2] |

| Main uses | ADHD, binge eating disorder[1] |

| Side effects | Loss of appetite, anxiety, diarrhea, trouble sleeping, irritability, nausea[1] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Dependence risk | High[1][3] |

| Addiction risk | Moderate |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth (capsules) |

| Onset of action | 2 h[4][5] |

| Duration of action | 10–12 h[3][4][5] |

| Defined daily dose | 30 mg[6] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a607047 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 96.4%[7] |

| Metabolism | Hydrolysis by enzymes in red blood cells initially. Subsequent metabolism follows Amphetamine#Pharmacokinetics. |

| Elimination half-life | ≤1 h (prodrug molecule) 9–11 h (dextroamphetamine) |

| Excretion | Renal: ~2% |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C15H25N3O |

| Molar mass | 263.385 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Lisdexamfetamine, sold under the brand name Vyvanse among others, is a medication that is used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in people over the age of five as well as for moderate to severe binge eating disorder in adults.[1] Lisdexamfetamine is taken by mouth.[1][8] In the United Kingdom it is usually less preferred than methylphenidate.[9] Its effects generally begin within 2 hours and last for up to 12 hours.[1]

Common side effects include loss of appetite, anxiety, diarrhea, trouble sleeping, irritability, and nausea.[1] Rare but serious side effects include mania, sudden cardiac death in those with underlying heart problems, and psychosis.[1] It has a high potential for abuse per the DEA.[1][8] Serotonin syndrome may occur if used with certain other medications.[1] Its use during pregnancy may result in harm to the baby and use during breastfeeding is not recommended by the manufacturer.[9][1][8] Lisdexamfetamine is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant that works after being converted by the body into dextroamphetamine.[1][2] Chemically, lisdexamfetamine is composed of the amino acid L-lysine, attached to dextroamphetamine.[10]

Lisdexamfetamine was approved for medical use in the United States in 2007.[1] A month's supply in the United Kingdom costs the British National Health Service about £58 as of 2019.[9] In the United States, the wholesale cost of this amount is about US$264.[11] In 2017, it was the 91st most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than eight million prescriptions.[12][13] It is a Schedule II controlled substance in the United Kingdom and a Schedule II controlled substance in the United States.[9][14]

Uses

Medical

Lisdexamfetamine is used primarily as a treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and binge eating disorder;[15] it has similar off-label uses as those of other pharmaceutical amphetamines.[3] Individuals over the age of 65 were not commonly tested in clinical trials of lisdexamfetamine for ADHD.[15]

Cognitive performance

In 2015, a systematic review and a meta-analysis of high quality clinical trials found that, when used at low (therapeutic) doses, amphetamine produces modest yet unambiguous improvements in cognition, including working memory, long-term episodic memory, inhibitory control, and some aspects of attention, in normal healthy adults;[16][17] these cognition-enhancing effects of amphetamine are known to be partially mediated through the indirect activation of both dopamine receptor D1 and adrenoceptor α2 in the prefrontal cortex.[18][16] A systematic review from 2014 found that low doses of amphetamine also improve memory consolidation, in turn leading to improved recall of information.[19] Therapeutic doses of amphetamine also enhance cortical network efficiency, an effect which mediates improvements in working memory in all individuals.[18][20] Amphetamine and other ADHD stimulants also improve task saliency (motivation to perform a task) and increase arousal (wakefulness), in turn promoting goal-directed behavior.[18][21][22] Stimulants such as amphetamine can improve performance on difficult and boring tasks and are used by some students as a study and test-taking aid.[18][22][23] Based upon studies of self-reported illicit stimulant use, 5–35% of college students use diverted ADHD stimulants, which are primarily used for enhancement of academic performance rather than as recreational drugs.[24][25][26] However, high amphetamine doses that are above the therapeutic range can interfere with working memory and other aspects of cognitive control.[18][22]

Physical performance

Amphetamine is used by some athletes for its psychological and athletic performance-enhancing effects, such as increased endurance and alertness;[27][28] however, non-medical amphetamine use is prohibited at sporting events that are regulated by collegiate, national, and international anti-doping agencies.[29][30] In healthy people at oral therapeutic doses, amphetamine has been shown to increase muscle strength, acceleration, athletic performance in anaerobic conditions, and endurance (i.e., it delays the onset of fatigue), while improving reaction time.[27][31][32] Amphetamine improves endurance and reaction time primarily through reuptake inhibition and release of dopamine in the central nervous system.[31][32][33] Amphetamine and other dopaminergic drugs also increase power output at fixed levels of perceived exertion by overriding a "safety switch", allowing the core temperature limit to increase in order to access a reserve capacity that is normally off-limits.[32][34][35] At therapeutic doses, the adverse effects of amphetamine do not impede athletic performance;[27][31] however, at much higher doses, amphetamine can induce effects that severely impair performance, such as rapid muscle breakdown and elevated body temperature.[36][31]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 30 mg by mouth.[6]

Contraindications

Pharmaceutical lisdexamfetamine dimesylate is contraindicated in patients with hypersensitivity to amphetamine products or any of the formulation's inactive ingredients.[15] It is also contraindicated in patients who have used a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) within the last 14 days.[15][37] Amphetamine products are contraindicated by the United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) in people with a history of drug abuse, heart disease, or severe agitation or anxiety, or in those currently experiencing arteriosclerosis, glaucoma, hyperthyroidism, or severe hypertension.[38] The USFDA advises anyone with bipolar disorder, depression, elevated blood pressure, liver or kidney problems, mania, psychosis, Raynaud's phenomenon, seizures, thyroid problems, tics, or Tourette syndrome to monitor their symptoms while taking amphetamine.[38] Amphetamine is classified in US pregnancy category C.[38] This means that detriments to the fetus have been observed in animal studies and adequate human studies have not been conducted; amphetamine may still be prescribed to pregnant women if the potential benefits outweigh the risks.[39] Amphetamine has also been shown to pass into breast milk, so the USFDA advises mothers to avoid breastfeeding when using it.[38] Due to the potential for stunted growth, the USFDA advises monitoring the height and weight of children and adolescents prescribed amphetamines.[38] Prescribing information approved by the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration further contraindicates anorexia.[40]

Side effects

Products containing lisdexamfetamine have a comparable drug safety profile to those containing amphetamine.[10]

Interactions

- Acidifying Agents: Drugs that acidify the urine, such as ascorbic acid, increase urinary excretion of dextroamphetamine, thus decreasing the half-life of dextroamphetamine in the body.[15][41]

- Alkalinizing Agents: Drugs that alkalinize the urine, such as sodium bicarbonate, decrease urinary excretion of dextroamphetamine, thus increasing the half-life of dextroamphetamine in the body.[15][41]

- Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors: Concomitant use of MAOIs and central nervous system stimulants such as lisdexamfetamine can cause a hypertensive crisis.[15]

Mechanism of action

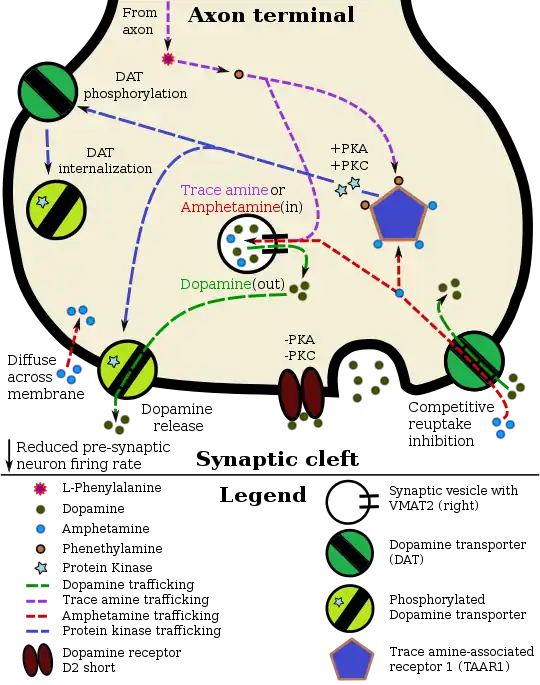

Pharmacodynamics of amphetamine in a dopamine neuron

|

Lisdexamfetamine is an inactive prodrug that is converted in the body to dextroamphetamine, a pharmacologically active compound which is responsible for the drug's activity.[49] After oral ingestion, lisdexamfetamine is broken down by enzymes in red blood cells to form L-lysine, a naturally occurring essential amino acid, and dextroamphetamine.[15] The conversion of lisdexamfetamine to dextroamphetamine is not affected by gastrointestinal pH and is unlikely to be affected by alterations in normal gastrointestinal transit times.[15][50]

The optical isomers of amphetamine, i.e., dextroamphetamine and levoamphetamine, are TAAR1 agonists and vesicular monoamine transporter 2 inhibitors that can enter monoamine neurons;[42][43] this allows them to release monoamine neurotransmitters (dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin, among others) from their storage sites in the presynaptic neuron, as well as prevent the reuptake of these neurotransmitters from the synaptic cleft.[42][43]

Lisdexamfetamine was developed with the goal of providing a long duration of effect that is consistent throughout the day, with reduced potential for abuse. The attachment of the amino acid lysine slows down the relative amount of dextroamphetamine available to the blood stream. Because no free dextroamphetamine is present in lisdexamfetamine capsules, dextroamphetamine does not become available through mechanical manipulation, such as crushing or simple extraction. A relatively sophisticated biochemical process is needed to produce dextroamphetamine from lisdexamfetamine.[50] As opposed to Adderall, which contains roughly equal parts of racemic amphetamine and dextroamphetamine salts, lisdexamfetamine is a single-enantiomer dextroamphetamine formula.[49][51] Studies conducted show that lisdexamfetamine dimesylate may have less abuse potential than dextroamphetamine and an abuse profile similar to diethylpropion at dosages that are FDA-approved for treatment of ADHD, but still has a high abuse potential when this dosage is exceeded by over 100%.[50]

Pharmacokinetics

The oral bioavailability of amphetamine varies with gastrointestinal pH;[36] it is well absorbed from the gut, and bioavailability is typically over 75% for dextroamphetamine.[52] Amphetamine is a weak base with a pKa of 9.9;[53] consequently, when the pH is basic, more of the drug is in its lipid soluble free base form, and more is absorbed through the lipid-rich cell membranes of the gut epithelium.[53][36] Conversely, an acidic pH means the drug is predominantly in a water-soluble cationic (salt) form, and less is absorbed.[53] Approximately 15–40% of amphetamine circulating in the bloodstream is bound to plasma proteins.[54] Following absorption, amphetamine readily distributes into most tissues in the body, with high concentrations occurring in cerebrospinal fluid and brain tissue.[55]

The half-lives of amphetamine enantiomers differ and vary with urine pH.[53] At normal urine pH, the half-lives of dextroamphetamine and levoamphetamine are 9–11 hours and 11–14 hours, respectively.[53] Highly acidic urine will reduce the enantiomer half-lives to 7 hours;[55] highly alkaline urine will increase the half-lives up to 34 hours.[55] The immediate-release and extended release variants of salts of both isomers reach peak plasma concentrations at 3 hours and 7 hours post-dose respectively.[53] Amphetamine is eliminated via the kidneys, with 30–40% of the drug being excreted unchanged at normal urinary pH.[53] When the urinary pH is basic, amphetamine is in its free base form, so less is excreted.[53] When urine pH is abnormal, the urinary recovery of amphetamine may range from a low of 1% to a high of 75%, depending mostly upon whether urine is too basic or acidic, respectively.[53] Following oral administration, amphetamine appears in urine within 3 hours.[55] Roughly 90% of ingested amphetamine is eliminated 3 days after the last oral dose.[55]

The prodrug lisdexamfetamine is not as sensitive to pH as amphetamine when being absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract;[15] following absorption into the blood stream, it is converted by red blood cell-associated enzymes to dextroamphetamine via hydrolysis.[15] The elimination half-life of lisdexamfetamine is generally less than 1 hour.[15]

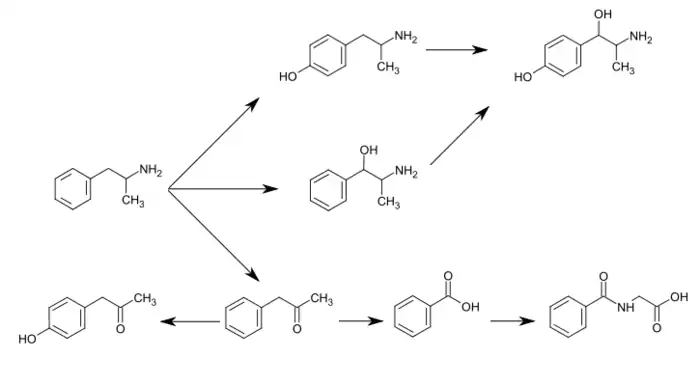

CYP2D6, dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH), flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 (FMO3), butyrate-CoA ligase (XM-ligase), and glycine N-acyltransferase (GLYAT) are the enzymes known to metabolize amphetamine or its metabolites in humans.[sources 1] Amphetamine has a variety of excreted metabolic products, including 4-hydroxyamphetamine, 4-hydroxynorephedrine, 4-hydroxyphenylacetone, benzoic acid, hippuric acid, norephedrine, and phenylacetone.[53][56] Among these metabolites, the active sympathomimetics are 4-hydroxyamphetamine,[57] 4-hydroxynorephedrine,[58] and norephedrine.[59] The main metabolic pathways involve aromatic para-hydroxylation, aliphatic alpha- and beta-hydroxylation, N-oxidation, N-dealkylation, and deamination.[53][60] The known metabolic pathways, detectable metabolites, and metabolizing enzymes in humans include the following:

Metabolic pathways of amphetamine in humans[sources 1]

|

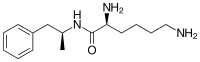

Chemistry

Lisdexamfetamine is a substituted amphetamine with an amide linkage formed by the condensation of dextroamphetamine with the carboxylate group of the essential amino acid L-lysine.[10] The reaction occurs with retention of stereochemistry, so the product lisdexamfetamine exists as a single stereoisomer. There are many possible names for lisdexamfetamine based on IUPAC nomenclature, but it is usually named as N-[(2S)-1-phenyl-2-propanyl]-L-lysinamide or (2S)-2,6-diamino-N-[(1S)-1-methyl-2-phenylethyl]hexanamide.[70] The condensation reaction occurs with loss of water:

- (S)-PhCH

2CH(CH

3)NH

2 + (S)-HOOCCH(NH

2)CH

2CH

2CH

2CH

2NH

2 → (S,S)-PhCH

2CH(CH

3)NHC(O)CH(NH

2)CH

2CH

2CH

2CH

2NH

2 + H

2O

Amine functional groups are vulnerable to oxidation in air and so pharmaceuticals containing them are usually formulated as salts where this moiety has been protonated. This increases stability, water solubility, and, by converting a molecular compound to an ionic compound, increases the melting point and thereby ensures a solid product.[71] In the case of lisdexamfetamine, this is achieved by reacting with two equivalents of methanesulfonic acid to produce the dimesylate salt, a water-soluble (792 mg mL−1) powder with a white to off-white color.[15]

- PhCH

2CH(CH

3)NHC(O)CH(NH

2)CH

2CH

2CH

2CH

2NH

2 + 2 CH

3SO

3H → [PhCH

2CH(CH

3)NHC(O)CH(NH+

3)CH

2CH

2CH

2CH

2NH+

3][CH

3SO−

3]

2

Comparison to other formulations

Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate is one marketed formulation delivering dextroamphetamine. The following table compares the drug to other amphetamine pharmaceuticals.

| drug | formula | molecular mass [note 2] |

amphetamine base [note 3] |

amphetamine base in equal doses |

doses with equal base content [note 4] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (g/mol) | (percent) | (30 mg dose) | ||||||||

| total | base | total | dextro- | levo- | dextro- | levo- | ||||

| dextroamphetamine sulfate[73][74] | (C9H13N)2•H2SO4 | 368.49 |

270.41 |

73.38% |

73.38% |

— |

22.0 mg |

— |

30.0 mg | |

| amphetamine sulfate[75] | (C9H13N)2•H2SO4 | 368.49 |

270.41 |

73.38% |

36.69% |

36.69% |

11.0 mg |

11.0 mg |

30.0 mg | |

| Adderall | 62.57% |

47.49% |

15.08% |

14.2 mg |

4.5 mg |

35.2 mg | ||||

| 25% | dextroamphetamine sulfate[73][74] | (C9H13N)2•H2SO4 | 368.49 |

270.41 |

73.38% |

73.38% |

— |

|||

| 25% | amphetamine sulfate[75] | (C9H13N)2•H2SO4 | 368.49 |

270.41 |

73.38% |

36.69% |

36.69% |

|||

| 25% | dextroamphetamine saccharate[76] | (C9H13N)2•C6H10O8 | 480.55 |

270.41 |

56.27% |

56.27% |

— |

|||

| 25% | amphetamine aspartate monohydrate[77] | (C9H13N)•C4H7NO4•H2O | 286.32 |

135.21 |

47.22% |

23.61% |

23.61% |

|||

| lisdexamfetamine dimesylate[15] | C15H25N3O•(CH4O3S)2 | 455.49 |

135.21 |

29.68% |

29.68% |

— |

8.9 mg |

— |

74.2 mg | |

| amphetamine base suspension[78] | C9H13N | 135.21 |

135.21 |

100% |

76.19% |

23.81% |

22.9 mg |

7.1 mg |

22.0 mg | |

History, society, and culture

Lisdexamfetamine was developed by New River Pharmaceuticals, who were bought by Takeda Pharmaceuticals through its acquisition of Shire Pharmaceuticals, shortly before it began being marketed. It was developed with the intention of creating a longer-lasting and less-easily abused version of dextroamphetamine, as the requirement of conversion into dextroamphetamine via enzymes in the red blood cells delays its onset of action, regardless of the route of administration.[79]

On 23 April 2008, the FDA approved lisdexamfetamine for treatment of ADHD in adults.[80] On 19 February 2009, Health Canada approved 30 mg and 50 mg capsules of lisdexamfetamine for treatment of ADHD.[81]

In January 2015, lisdexamfetamine was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of binge eating disorder in adults.[82]

Production quotas for 2016 in the United States were 29,750 kilograms.[83]

Names

Lisdexamfetamine is a contraction of L-lysine-dextroamphetamine.

As of July 2014 lisdexamfetamine was sold under the following brands: Elvanse, Samexid, Tyvense, Venvanse, and Vyvanse.[84]

Research

Depression

Some clinical trials that used lisdexamfetamine as an add-on therapy with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) for treatment-resistant depression indicated that this is no more effective than the use of an SSRI or SNRI alone.[85] Other studies indicated that psychostimulants potentiated antidepressants, and were under-prescribed for treatment resistant depression. In those studies, patients showed significant improvement in energy, mood, and psychomotor activity.[86] In February 2014, Shire announced that two late-stage clinical trials had shown that Vyvanse was not an effective treatment for depression.[87]

Society and culture

Cost

A month's supply in the United Kingdom costs the British National Health Service about £58 as of 2019.[9] In the United States, the wholesale cost of this amount is about US$264.[11] In 2017, it was the 91st most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than eight million prescriptions.[12][13]

.svg.png.webp) Lisdexamfetamine costs (US)

Lisdexamfetamine costs (US).svg.png.webp) Lisdexamfetamine prescriptions (US)

Lisdexamfetamine prescriptions (US)

Notes

- ↑ 4-Hydroxyamphetamine has been shown to be metabolized into 4-hydroxynorephedrine by dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DBH) in vitro and it is presumed to be metabolized similarly in vivo.[61][65] Evidence from studies that measured the effect of serum DBH concentrations on 4-hydroxyamphetamine metabolism in humans suggests that a different enzyme may mediate the conversion of 4-hydroxyamphetamine to 4-hydroxynorephedrine;[65][67] however, other evidence from animal studies suggests that this reaction is catalyzed by DBH in synaptic vesicles within noradrenergic neurons in the brain.[68][69]

- ↑ For uniformity, molecular masses were calculated using the Lenntech Molecular Weight Calculator[72] and were within 0.01g/mol of published pharmaceutical values.

- ↑ Amphetamine base percentage = molecular massbase / molecular masstotal. Amphetamine base percentage for Adderall = sum of component percentages / 4.

- ↑ dose = (1 / amphetamine base percentage) × scaling factor = (molecular masstotal / molecular massbase) × scaling factor. The values in this column were scaled to a 30 mg dose of dextroamphetamine sulfate. Due to pharmacological differences between these medications (e.g., differences in the release, absorption, conversion, concentration, differing effects of enantiomers, half-life, etc.), the listed values should not be considered equipotent doses.

- Image legend

Reference notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Lisdexamfetamine Dimesylate Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- 1 2 Heal DJ, Smith SL, Gosden J, Nutt DJ (June 2013). "Amphetamine, past and present – a pharmacological and clinical perspective". J. Psychopharmacol. 27 (6): 479–496. doi:10.1177/0269881113482532. PMC 3666194. PMID 23539642.

- 1 2 3 Stahl SM (March 2017). "Lisdexamfetamine". Prescriber's Guide: Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology (6th ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 379–384. ISBN 9781108228749.

- 1 2 Millichap JG (2010). "Chapter 9: Medications for ADHD". In Millichap JG (ed.). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Handbook: A Physician's Guide to ADHD (2nd ed.). New York, USA: Springer. p. 112. ISBN 9781441913968.

Table 9.2 Dextroamphetamine formulations of stimulant medication

Dexedrine [Peak:2–3 h] [Duration:5–6 h] ...

Adderall [Peak:2–3 h] [Duration:5–7 h]

Dexedrine spansules [Peak:7–8 h] [Duration:12 h] ...

Adderall XR [Peak:7–8 h] [Duration:12 h]

Vyvanse [Peak:3–4 h] [Duration:12 h] - 1 2 Brams M, Mao AR, Doyle RL (September 2008). "Onset of efficacy of long-acting psychostimulants in pediatric attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Postgrad. Med. 120 (3): 69–88. doi:10.3810/pgm.2008.09.1909. PMID 18824827.

Onset of efficacy was earliest for d-MPH-ER at 0.5 hours, followed by d, l-MPH-LA at 1 to 2 hours, MCD at 1.5 hours, d, l-MPH-OR at 1 to 2 hours, MAS-XR at 1.5 to 2 hours, MTS at 2 hours, and LDX at approximately 2 hours. ... MAS-XR, and LDX have a long duration of action at 12 hours postdose

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ↑ "Public Assessment Report Decentralised Procedure" (PDF). MHRA. p. 14. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 October 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 British national formulary: BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. pp. 348–349. ISBN 9780857113382.

- 1 2 3 Blick SK, Keating GM (2007). "Lisdexamfetamine". Paediatric Drugs. 9 (2): 129–135, discussion 136–138. doi:10.2165/00148581-200709020-00007. PMID 17407369.

- 1 2 "NADAC as of 2019-02-27". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- 1 2 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- 1 2 "Lisdexamfetamine Dimesylate - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ Drugs of Abuse (PDF). Drug Enforcement Administration • U.S. Department of Justice. 2017. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Vyvanse- lisdexamfetamine dimesylate capsule Vyvanse- lisdexamfetamine dimesylate tablet, chewable". DailyMed. Shire US Inc. 30 October 2019. Archived from the original on 2 October 2019. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- 1 2 Spencer RC, Devilbiss DM, Berridge CW (June 2015). "The Cognition-Enhancing Effects of Psychostimulants Involve Direct Action in the Prefrontal Cortex". Biological Psychiatry. 77 (11): 940–950. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.09.013. PMC 4377121. PMID 25499957. Archived from the original on 2 May 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

The procognitive actions of psychostimulants are only associated with low doses. Surprisingly, despite nearly 80 years of clinical use, the neurobiology of the procognitive actions of psychostimulants has only recently been systematically investigated. Findings from this research unambiguously demonstrate that the cognition-enhancing effects of psychostimulants involve the preferential elevation of catecholamines in the PFC and the subsequent activation of norepinephrine α2 and dopamine D1 receptors. ... This differential modulation of PFC-dependent processes across dose appears to be associated with the differential involvement of noradrenergic α2 versus α1 receptors. Collectively, this evidence indicates that at low, clinically relevant doses, psychostimulants are devoid of the behavioral and neurochemical actions that define this class of drugs and instead act largely as cognitive enhancers (improving PFC-dependent function). ... In particular, in both animals and humans, lower doses maximally improve performance in tests of working memory and response inhibition, whereas maximal suppression of overt behavior and facilitation of attentional processes occurs at higher doses.

- ↑ Ilieva IP, Hook CJ, Farah MJ (June 2015). "Prescription Stimulants' Effects on Healthy Inhibitory Control, Working Memory, and Episodic Memory: A Meta-analysis". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 27 (6): 1069–1089. doi:10.1162/jocn_a_00776. PMID 25591060. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

Specifically, in a set of experiments limited to high-quality designs, we found significant enhancement of several cognitive abilities. ... The results of this meta-analysis ... do confirm the reality of cognitive enhancing effects for normal healthy adults in general, while also indicating that these effects are modest in size.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 13: Higher Cognitive Function and Behavioral Control". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 318, 321. ISBN 9780071481274.

Therapeutic (relatively low) doses of psychostimulants, such as methylphenidate and amphetamine, improve performance on working memory tasks both in normal subjects and those with ADHD. ... stimulants act not only on working memory function, but also on general levels of arousal and, within the nucleus accumbens, improve the saliency of tasks. Thus, stimulants improve performance on effortful but tedious tasks ... through indirect stimulation of dopamine and norepinephrine receptors. ...

Beyond these general permissive effects, dopamine (acting via D1 receptors) and norepinephrine (acting at several receptors) can, at optimal levels, enhance working memory and aspects of attention. - ↑ Bagot KS, Kaminer Y (April 2014). "Efficacy of stimulants for cognitive enhancement in non-attention deficit hyperactivity disorder youth: a systematic review". Addiction. 109 (4): 547–557. doi:10.1111/add.12460. PMC 4471173. PMID 24749160.

Amphetamine has been shown to improve consolidation of information (0.02 ≥ P ≤ 0.05), leading to improved recall.

- ↑ Devous MD, Trivedi MH, Rush AJ (April 2001). "Regional cerebral blood flow response to oral amphetamine challenge in healthy volunteers". Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 42 (4): 535–542. PMID 11337538.

- ↑ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 10: Neural and Neuroendocrine Control of the Internal Milieu". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 266. ISBN 9780071481274.

Dopamine acts in the nucleus accumbens to attach motivational significance to stimuli associated with reward.

- 1 2 3 Wood S, Sage JR, Shuman T, Anagnostaras SG (January 2014). "Psychostimulants and cognition: a continuum of behavioral and cognitive activation". Pharmacological Reviews. 66 (1): 193–221. doi:10.1124/pr.112.007054. PMC 3880463. PMID 24344115.

- ↑ Twohey M (26 March 2006). "Pills become an addictive study aid". JS Online. Archived from the original on 15 August 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- ↑ Teter CJ, McCabe SE, LaGrange K, Cranford JA, Boyd CJ (October 2006). "Illicit use of specific prescription stimulants among college students: prevalence, motives, and routes of administration". Pharmacotherapy. 26 (10): 1501–1510. doi:10.1592/phco.26.10.1501. PMC 1794223. PMID 16999660.

- ↑ Weyandt LL, Oster DR, Marraccini ME, Gudmundsdottir BG, Munro BA, Zavras BM, Kuhar B (September 2014). "Pharmacological interventions for adolescents and adults with ADHD: stimulant and nonstimulant medications and misuse of prescription stimulants". Psychology Research and Behavior Management. 7: 223–249. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S47013. PMC 4164338. PMID 25228824.

misuse of prescription stimulants has become a serious problem on college campuses across the US and has been recently documented in other countries as well. ... Indeed, large numbers of students claim to have engaged in the nonmedical use of prescription stimulants, which is reflected in lifetime prevalence rates of prescription stimulant misuse ranging from 5% to nearly 34% of students.

- ↑ Clemow DB, Walker DJ (September 2014). "The potential for misuse and abuse of medications in ADHD: a review". Postgraduate Medicine. 126 (5): 64–81. doi:10.3810/pgm.2014.09.2801. PMID 25295651.

Overall, the data suggest that ADHD medication misuse and diversion are common health care problems for stimulant medications, with the prevalence believed to be approximately 5% to 10% of high school students and 5% to 35% of college students, depending on the study.

- 1 2 3 Liddle DG, Connor DJ (June 2013). "Nutritional supplements and ergogenic AIDS". Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice. 40 (2): 487–505. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2013.02.009. PMID 23668655.

Amphetamines and caffeine are stimulants that increase alertness, improve focus, decrease reaction time, and delay fatigue, allowing for an increased intensity and duration of training ...

Physiologic and performance effects

• Amphetamines increase dopamine/norepinephrine release and inhibit their reuptake, leading to central nervous system (CNS) stimulation

• Amphetamines seem to enhance athletic performance in anaerobic conditions 39 40

• Improved reaction time

• Increased muscle strength and delayed muscle fatigue

• Increased acceleration

• Increased alertness and attention to task - ↑

- ↑ Bracken NM (January 2012). "National Study of Substance Use Trends Among NCAA College Student-Athletes" (PDF). NCAA Publications. National Collegiate Athletic Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ↑ Docherty JR (June 2008). "Pharmacology of stimulants prohibited by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA)". British Journal of Pharmacology. 154 (3): 606–622. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.124. PMC 2439527. PMID 18500382.

- 1 2 3 4 Parr JW (July 2011). "Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and the athlete: new advances and understanding". Clinics in Sports Medicine. 30 (3): 591–610. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2011.03.007. PMID 21658550.

In 1980, Chandler and Blair47 showed significant increases in knee extension strength, acceleration, anaerobic capacity, time to exhaustion during exercise, pre-exercise and maximum heart rates, and time to exhaustion during maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max) testing after administration of 15 mg of dextroamphetamine versus placebo. Most of the information to answer this question has been obtained in the past decade through studies of fatigue rather than an attempt to systematically investigate the effect of ADHD drugs on exercise.

- 1 2 3 Roelands B, de Koning J, Foster C, Hettinga F, Meeusen R (May 2013). "Neurophysiological determinants of theoretical concepts and mechanisms involved in pacing". Sports Medicine. 43 (5): 301–311. doi:10.1007/s40279-013-0030-4. PMID 23456493.

In high-ambient temperatures, dopaminergic manipulations clearly improve performance. The distribution of the power output reveals that after dopamine reuptake inhibition, subjects are able to maintain a higher power output compared with placebo. ... Dopaminergic drugs appear to override a safety switch and allow athletes to use a reserve capacity that is 'off-limits' in a normal (placebo) situation.

- ↑ Parker KL, Lamichhane D, Caetano MS, Narayanan NS (October 2013). "Executive dysfunction in Parkinson's disease and timing deficits". Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. 7: 75. doi:10.3389/fnint.2013.00075. PMC 3813949. PMID 24198770.

Manipulations of dopaminergic signaling profoundly influence interval timing, leading to the hypothesis that dopamine influences internal pacemaker, or "clock," activity. For instance, amphetamine, which increases concentrations of dopamine at the synaptic cleft advances the start of responding during interval timing, whereas antagonists of D2 type dopamine receptors typically slow timing;... Depletion of dopamine in healthy volunteers impairs timing, while amphetamine releases synaptic dopamine and speeds up timing.

- ↑ Rattray B, Argus C, Martin K, Northey J, Driller M (March 2015). "Is it time to turn our attention toward central mechanisms for post-exertional recovery strategies and performance?". Frontiers in Physiology. 6: 79. doi:10.3389/fphys.2015.00079. PMC 4362407. PMID 25852568.

Aside from accounting for the reduced performance of mentally fatigued participants, this model rationalizes the reduced RPE and hence improved cycling time trial performance of athletes using a glucose mouthwash (Chambers et al., 2009) and the greater power output during a RPE matched cycling time trial following amphetamine ingestion (Swart, 2009). ... Dopamine stimulating drugs are known to enhance aspects of exercise performance (Roelands et al., 2008)

- ↑ Roelands B, De Pauw K, Meeusen R (June 2015). "Neurophysiological effects of exercise in the heat". Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 25 (Suppl 1): 65–78. doi:10.1111/sms.12350. PMID 25943657.

This indicates that subjects did not feel they were producing more power and consequently more heat. The authors concluded that the "safety switch" or the mechanisms existing in the body to prevent harmful effects are overridden by the drug administration (Roelands et al., 2008b). Taken together, these data indicate strong ergogenic effects of an increased DA concentration in the brain, without any change in the perception of effort.

- 1 2 3 "Adderall XR- dextroamphetamine sulfate, dextroamphetamine saccharate, amphetamine sulfate and amphetamine aspartate capsule, extended release". DailyMed. Shire US Inc. 17 July 2019. Archived from the original on 17 September 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- ↑ Heedes G; Ailakis J. "Amphetamine (PIM 934)". INCHEM. International Programme on Chemical Safety. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Adderall XR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Shire US Inc. December 2013. pp. 4–6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ↑ "FDA Pregnancy Categories" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. 21 October 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ↑ "Dexamphetamine tablets". Therapeutic Goods Administration. Archived from the original on 13 September 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- 1 2 "Adderall XR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Shire US Inc. December 2013. pp. 8–10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Miller GM (January 2011). "The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity". J. Neurochem. 116 (2): 164–176. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. PMC 3005101. PMID 21073468.

- 1 2 3 4 Eiden LE, Weihe E (January 2011). "VMAT2: a dynamic regulator of brain monoaminergic neuronal function interacting with drugs of abuse". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1216: 86–98. Bibcode:2011NYASA1216...86E. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05906.x. PMC 4183197. PMID 21272013.

VMAT2 is the CNS vesicular transporter for not only the biogenic amines DA, NE, EPI, 5-HT, and HIS, but likely also for the trace amines TYR, PEA, and thyronamine (THYR) ... [Trace aminergic] neurons in mammalian CNS would be identifiable as neurons expressing VMAT2 for storage, and the biosynthetic enzyme aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AADC).

- ↑ Sulzer D, Cragg SJ, Rice ME (August 2016). "Striatal dopamine neurotransmission: regulation of release and uptake". Basal Ganglia. 6 (3): 123–148. doi:10.1016/j.baga.2016.02.001. PMC 4850498. PMID 27141430.

Despite the challenges in determining synaptic vesicle pH, the proton gradient across the vesicle membrane is of fundamental importance for its function. Exposure of isolated catecholamine vesicles to protonophores collapses the pH gradient and rapidly redistributes transmitter from inside to outside the vesicle. ... Amphetamine and its derivatives like methamphetamine are weak base compounds that are the only widely used class of drugs known to elicit transmitter release by a non-exocytic mechanism. As substrates for both DAT and VMAT, amphetamines can be taken up to the cytosol and then sequestered in vesicles, where they act to collapse the vesicular pH gradient.

- ↑ Ledonne A, Berretta N, Davoli A, Rizzo GR, Bernardi G, Mercuri NB (July 2011). "Electrophysiological effects of trace amines on mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons". Front. Syst. Neurosci. 5: 56. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2011.00056. PMC 3131148. PMID 21772817.

Three important new aspects of TAs action have recently emerged: (a) inhibition of firing due to increased release of dopamine; (b) reduction of D2 and GABAB receptor-mediated inhibitory responses (excitatory effects due to disinhibition); and (c) a direct TA1 receptor-mediated activation of GIRK channels which produce cell membrane hyperpolarization.

- ↑ "TAAR1". GenAtlas. University of Paris. 28 January 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

• tonically activates inwardly rectifying K(+) channels, which reduces the basal firing frequency of dopamine (DA) neurons of the ventral tegmental area (VTA)

- ↑ Underhill SM, Wheeler DS, Li M, Watts SD, Ingram SL, Amara SG (July 2014). "Amphetamine modulates excitatory neurotransmission through endocytosis of the glutamate transporter EAAT3 in dopamine neurons". Neuron. 83 (2): 404–416. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2014.05.043. PMC 4159050. PMID 25033183.

AMPH also increases intracellular calcium (Gnegy et al., 2004) that is associated with calmodulin/CamKII activation (Wei et al., 2007) and modulation and trafficking of the DAT (Fog et al., 2006; Sakrikar et al., 2012). ... For example, AMPH increases extracellular glutamate in various brain regions including the striatum, VTA and NAc (Del Arco et al., 1999; Kim et al., 1981; Mora and Porras, 1993; Xue et al., 1996), but it has not been established whether this change can be explained by increased synaptic release or by reduced clearance of glutamate. ... DHK-sensitive, EAAT2 uptake was not altered by AMPH (Figure 1A). The remaining glutamate transport in these midbrain cultures is likely mediated by EAAT3 and this component was significantly decreased by AMPH

- ↑ Vaughan RA, Foster JD (September 2013). "Mechanisms of dopamine transporter regulation in normal and disease states". Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 34 (9): 489–496. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2013.07.005. PMC 3831354. PMID 23968642.

AMPH and METH also stimulate DA efflux, which is thought to be a crucial element in their addictive properties [80], although the mechanisms do not appear to be identical for each drug [81]. These processes are PKCβ– and CaMK–dependent [72, 82], and PKCβ knock-out mice display decreased AMPH-induced efflux that correlates with reduced AMPH-induced locomotion [72].

- 1 2 "Identification". Lisdexamfetamine. DrugBank. University of Alberta. 16 September 2013. Archived from the original on 19 June 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- 1 2 3 Jasinski DR, Krishnan S (June 2009). "Abuse liability and safety of oral lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in individuals with a history of stimulant abuse". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford). 23 (4): 419–427. doi:10.1177/0269881109103113. PMID 19329547.

- ↑ "Adderall XR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. pp. 1–18. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ↑ "Pharmacology". Dextroamphetamine. DrugBank. University of Alberta. 8 February 2013. Archived from the original on 6 August 2019. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Adderall XR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Shire US Inc. December 2013. pp. 12–13. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ↑ "Pharmacology". Amphetamine. DrugBank. University of Alberta. 8 February 2013. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Metabolism/Pharmacokinetics". Amphetamine. United States National Library of Medicine – Toxicology Data Network. Hazardous Substances Data Bank. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

Duration of effect varies depending on agent and urine pH. Excretion is enhanced in more acidic urine. Half-life is 7 to 34 hours and is, in part, dependent on urine pH (half-life is longer with alkaline urine). ... Amphetamines are distributed into most body tissues with high concentrations occurring in the brain and CSF. Amphetamine appears in the urine within about 3 hours following oral administration. ... Three days after a dose of (+ or -)-amphetamine, human subjects had excreted 91% of the (14)C in the urine

- 1 2 3 Santagati NA, Ferrara G, Marrazzo A, Ronsisvalle G (September 2002). "Simultaneous determination of amphetamine and one of its metabolites by HPLC with electrochemical detection". Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 30 (2): 247–255. doi:10.1016/S0731-7085(02)00330-8. PMID 12191709.

- ↑ "Compound Summary". p-Hydroxyamphetamine. PubChem Compound Database. United States National Library of Medicine – National Center for Biotechnology Information. Archived from the original on 7 June 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ↑ "Compound Summary". p-Hydroxynorephedrine. PubChem Compound Database. United States National Library of Medicine – National Center for Biotechnology Information. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ↑ "Compound Summary". Phenylpropanolamine. PubChem Compound Database. United States National Library of Medicine – National Center for Biotechnology Information. Archived from the original on 29 September 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ↑ "Pharmacology and Biochemistry". Amphetamine. Pubchem Compound Database. United States National Library of Medicine – National Center for Biotechnology Information. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- 1 2 Glennon RA (2013). "Phenylisopropylamine stimulants: amphetamine-related agents". In Lemke TL, Williams DA, Roche VF, Zito W (eds.). Foye's principles of medicinal chemistry (7th ed.). Philadelphia, USA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 646–648. ISBN 9781609133450.

The simplest unsubstituted phenylisopropylamine, 1-phenyl-2-aminopropane, or amphetamine, serves as a common structural template for hallucinogens and psychostimulants. Amphetamine produces central stimulant, anorectic, and sympathomimetic actions, and it is the prototype member of this class (39). ... The phase 1 metabolism of amphetamine analogs is catalyzed by two systems: cytochrome P450 and flavin monooxygenase. ... Amphetamine can also undergo aromatic hydroxylation to p-hydroxyamphetamine. ... Subsequent oxidation at the benzylic position by DA β-hydroxylase affords p-hydroxynorephedrine. Alternatively, direct oxidation of amphetamine by DA β-hydroxylase can afford norephedrine.

- ↑ Taylor KB (January 1974). "Dopamine-beta-hydroxylase. Stereochemical course of the reaction" (PDF). Journal of Biological Chemistry. 249 (2): 454–458. PMID 4809526. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

Dopamine-β-hydroxylase catalyzed the removal of the pro-R hydrogen atom and the production of 1-norephedrine, (2S,1R)-2-amino-1-hydroxyl-1-phenylpropane, from d-amphetamine.

- ↑ Krueger SK, Williams DE (June 2005). "Mammalian flavin-containing monooxygenases: structure/function, genetic polymorphisms and role in drug metabolism". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 106 (3): 357–387. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.01.001. PMC 1828602. PMID 15922018.

Table 5: N-containing drugs and xenobiotics oxygenated by FMO - ↑ Cashman JR, Xiong YN, Xu L, Janowsky A (March 1999). "N-oxygenation of amphetamine and methamphetamine by the human flavin-containing monooxygenase (form 3): role in bioactivation and detoxication". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 288 (3): 1251–1260. PMID 10027866.

- 1 2 3 Sjoerdsma A, von Studnitz W (April 1963). "Dopamine-beta-oxidase activity in man, using hydroxyamphetamine as substrate". British Journal of Pharmacology and Chemotherapy. 20: 278–284. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1963.tb01467.x. PMC 1703637. PMID 13977820.

Hydroxyamphetamine was administered orally to five human subjects ... Since conversion of hydroxyamphetamine to hydroxynorephedrine occurs in vitro by the action of dopamine-β-oxidase, a simple method is suggested for measuring the activity of this enzyme and the effect of its inhibitors in man. ... The lack of effect of administration of neomycin to one patient indicates that the hydroxylation occurs in body tissues. ... a major portion of the β-hydroxylation of hydroxyamphetamine occurs in non-adrenal tissue. Unfortunately, at the present time one cannot be completely certain that the hydroxylation of hydroxyamphetamine in vivo is accomplished by the same enzyme which converts dopamine to noradrenaline.

- 1 2 Badenhorst CP, van der Sluis R, Erasmus E, van Dijk AA (September 2013). "Glycine conjugation: importance in metabolism, the role of glycine N-acyltransferase, and factors that influence interindividual variation". Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 9 (9): 1139–1153. doi:10.1517/17425255.2013.796929. PMID 23650932.

Figure 1. Glycine conjugation of benzoic acid. The glycine conjugation pathway consists of two steps. First benzoate is ligated to CoASH to form the high-energy benzoyl-CoA thioester. This reaction is catalyzed by the HXM-A and HXM-B medium-chain acid:CoA ligases and requires energy in the form of ATP. ... The benzoyl-CoA is then conjugated to glycine by GLYAT to form hippuric acid, releasing CoASH. In addition to the factors listed in the boxes, the levels of ATP, CoASH, and glycine may influence the overall rate of the glycine conjugation pathway.

- ↑ Horwitz D, Alexander RW, Lovenberg W, Keiser HR (May 1973). "Human serum dopamine-β-hydroxylase. Relationship to hypertension and sympathetic activity". Circulation Research. 32 (5): 594–599. doi:10.1161/01.RES.32.5.594. PMID 4713201.

The biologic significance of the different levels of serum DβH activity was studied in two ways. First, in vivo ability to β-hydroxylate the synthetic substrate hydroxyamphetamine was compared in two subjects with low serum DβH activity and two subjects with average activity. ... In one study, hydroxyamphetamine (Paredrine), a synthetic substrate for DβH, was administered to subjects with either low or average levels of serum DβH activity. The percent of the drug hydroxylated to hydroxynorephedrine was comparable in all subjects (6.5-9.62) (Table 3).

- ↑ Freeman JJ, Sulser F (December 1974). "Formation of p-hydroxynorephedrine in brain following intraventricular administration of p-hydroxyamphetamine". Neuropharmacology. 13 (12): 1187–1190. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(74)90069-0. PMID 4457764.

In species where aromatic hydroxylation of amphetamine is the major metabolic pathway, p-hydroxyamphetamine (POH) and p-hydroxynorephedrine (PHN) may contribute to the pharmacological profile of the parent drug. ... The location of the p-hydroxylation and β-hydroxylation reactions is important in species where aromatic hydroxylation of amphetamine is the predominant pathway of metabolism. Following systemic administration of amphetamine to rats, POH has been found in urine and in plasma.

The observed lack of a significant accumulation of PHN in brain following the intraventricular administration of (+)-amphetamine and the formation of appreciable amounts of PHN from (+)-POH in brain tissue in vivo supports the view that the aromatic hydroxylation of amphetamine following its systemic administration occurs predominantly in the periphery, and that POH is then transported through the blood-brain barrier, taken up by noradrenergic neurones in brain where (+)-POH is converted in the storage vesicles by dopamine β-hydroxylase to PHN. - ↑ Matsuda LA, Hanson GR, Gibb JW (December 1989). "Neurochemical effects of amphetamine metabolites on central dopaminergic and serotonergic systems". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 251 (3): 901–908. PMID 2600821.

The metabolism of p-OHA to p-OHNor is well documented and dopamine-β hydroxylase present in noradrenergic neurons could easily convert p-OHA to p-OHNor after intraventricular administration.

- ↑ "Lidsexamfetamine". ChemSpider. Royal Society of Chemistry. 2015. Archived from the original on 27 April 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ↑ Stahl, P. Heinrich; Wermuth, Camille G., eds. (2011). Pharmaceutical Salts: Properties, Selection, and Use (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-3-90639-051-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editorlink2=ignored (help) - ↑ "Molecular Weight Calculator". Lenntech. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- 1 2 "Dextroamphetamine Sulfate USP". Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals. March 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- 1 2 "D-amphetamine sulfate". Tocris. 2015. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- 1 2 "Amphetamine Sulfate USP". Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals. March 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ↑ "Dextroamphetamine Saccharate". Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals. March 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ↑ "Amphetamine Aspartate". Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals. March 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ↑ Mattingly, G (May 2010). "Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate: a prodrug stimulant for the treatment of ADHD in children and adults". CNS Spectrums. 15 (5): 315–25. doi:10.1017/S1092852900027541. PMID 20448522. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- ↑ "FDA Adult Approval of Vyvanse – FDA Label and Approval History" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ↑ Health Canada Notice of Compliance – Vyvanse. 19 February 2009, retrieved on 9 March 2009.

- ↑ "Press Announcements – FDA expands uses of Vyvanse to treat binge-eating disorder". FDA. 30 January 2015. Archived from the original on 26 January 2018. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ↑ "DEA Office of Diversion Control" (PDF). DEA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ↑ "Lisdexamfetamine international brands". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ↑ Dale E, Bang-Andersen B, Sánchez C (May 2015). "Emerging mechanisms and treatments for depression beyond SSRIs and SNRIs". Biochem. Pharmacol. 95 (2): 81–97. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2015.03.011. PMID 25813654.

- ↑ Stotz, G.; Woggon, B.; Angst, J. (1999). "Psychostimulants in the therapy of treatment-resistant depression Review of the literature and findings from a retrospective study in 65 depressed patients". Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 1 (3): 165–74. PMC 3181580. PMID 22034135.

- ↑ Hirschler, Ben (7 February 2014). "UPDATE 2-Shire scraps Vyvanse for depression after failed trials". Reuters. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

External links

| External sites: |

|

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |