Amphotericin B

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Fungizone, Mysteclin-F, AmBisome, others |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Antifungal |

| Main uses | Cryptococcal meningitis, histoplasmosis, penicilliosis[1] |

| Side effects | Fever, chills, and headaches, kidney problems[2] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | usually I.V. (slow infusion only) |

| Defined daily dose | 35 mg (by injection)[3] 40 to 400 mg (by mouth)[4][5] 200 mg (vaginal)[6] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682643 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 100% (IV) |

| Metabolism | Kidney |

| Elimination half-life | initial phase : 24 hours, second phase : approx. 15 days |

| Excretion | 40% found in urine after single cumulated over several days biliar excretion also important |

| Chemical and physical data | |

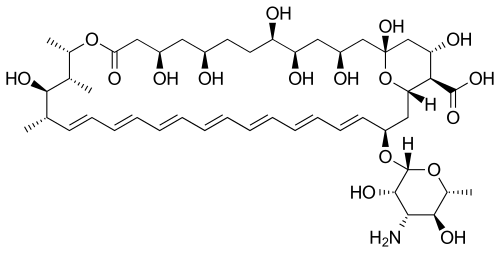

| Formula | C47H73NO17 |

| Molar mass | 924.091 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 170 °C (338 °F) |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Amphotericin B is an antifungal medication used for serious fungal infections and leishmaniasis.[7] The fungal infections it is used to treat include aspergillosis, blastomycosis, candidiasis, coccidioidomycosis, and cryptococcosis.[2] For certain infections it is given with flucytosine.[8] It is typically given by injection into a vein.[2]

Common side effects include a reaction with fever, chills, and headaches soon after the medication is given, as well as kidney problems.[2] Allergic symptoms including anaphylaxis may occur.[2] Other serious side effects include low blood potassium and inflammation of the heart.[7] It appears to be relatively safe in pregnancy.[2] There is a lipid formulation that has a lower risk of side effects.[2] It is in the polyene class of medications and works in part by interfering with the cell membrane of the fungus.[7][2]

Amphotericin B was isolated from Streptomyces nodosus in 1955 and came into medical use in 1958.[9][10] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[11] It is available as a generic medication.[2] The cost in the developing world of a course of treatment as of 2010 is between US$162 and 229.[7]

Medical uses

Fungal infection

One of the main uses of amphotericin B is treating a wide range of systemic fungal infections. Due to its extensive side effects, it is often reserved for severe infections in critically ill, or immunocompromised patients. It is considered first line therapy for invasive mucormycosis infections, cryptococcal meningitis, and certain aspergillus and candidal infections.[13][14] It has been a highly effective drug for over fifty years in large part because it has a low incidence of drug resistance in the pathogens it treats. This is because amphotericin B resistance requires sacrifices on the part of the pathogen that make it susceptible to the host environment, and too weak to cause infection.[15]

Protozoal infection

Amphotericin B is used for life-threatening protozoan infections such as visceral leishmaniasis[16] and primary amoebic meningoencephalitis.[17]

Susceptibility

Amphotericin B susceptibility for a selection of medically important fungi.

| Species | Amphotericin B

MIC breakpoint (mg/L) |

|---|---|

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 1[18] |

| Aspergillus terreus | Resistant[18][19] |

| Candida albicans | 1[18] |

| Candida krusei | 1[18] |

| Candida glabrata | 1[18] |

| Candida lusitaniae | Intrinsically resistant[19] |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | 2[20] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | 2[20] |

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 40 mg to 400 mg by mouth,[4][5] 200 mg vaginally,[6] and 35 mg by injection.[3] The conventional injection is given at a dose of 0.7 to 1 mg/kg once per day.[1] Treatment is often for 2 weeks.[1] The liposomal injection is given at a dose of 3 mg/kg.[21]

Side effects

Amphotericin B is well known for its severe and potentially lethal side effects. Very often, it causes a serious reaction soon after infusion (within 1 to 3 hours), consisting of high fever, shaking chills, hypotension, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, headache, dyspnea and tachypnea, drowsiness, and generalized weakness. The violent chills and fevers have caused the drug to be nicknamed "shake and bake".[22][23] This reaction sometimes subsides with later applications of the drug, and may in part be due to histamine liberation. An increase in prostaglandin synthesis may also play a role. This nearly universal febrile response necessitates a critical (and diagnostically difficult) professional determination as to whether the onset of high fever is a novel symptom of a fast-progressing disease, or merely the effect of the drug. To decrease the likelihood and severity of the symptoms, initial doses should be low, and increased slowly. Paracetamol, pethidine, diphenhydramine, and hydrocortisone have all been used to treat or prevent the syndrome, but the prophylactic use of these drugs is often limited by the patient's condition.

Intravenously administered amphotericin B in therapeutic doses has also been associated with multiple organ damage. Kidney damage is a frequently reported side effect, and can be severe and/or irreversible. Less kidney toxicity has been reported with liposomal formulations (such as AmBisome) and it has become preferred in patients with preexisting renal injury.[24][25] The integrity of the liposome is disrupted when it binds to the fungal cell wall, but is not affected by the mammalian cell membrane,[26] so the association with liposomes decreases the exposure of the kidneys to amphotericin B, which explains its less nephrotoxic effects.[27]

In addition, electrolyte imbalances such as hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia are also common.[28] In the liver, increased liver enzymes and hepatotoxicity (up to and including fulminant liver failure) are common. In the circulatory system, several forms of anemia and other blood dyscrasias (leukopenia, thrombopenia), serious cardiac arrhythmias (including ventricular fibrillation), and even frank cardiac failure have been reported. Skin reactions, including serious forms, are also possible.

Interactions

- Flucytosine: Toxicity of flucytosine is increased and allows a lower dose of amphotericin B. Amphotericin B may also facilitate entry of flucystosine into the fungal cell by interfering with the permeability of the fungal cell membrane.

- Diuretics or cisplatin: Increased renal toxicity and increased risk of hypokalemia

- Corticosteroids: Increased risk of hypokalemia

- Cytostatic drugs: Increased risk of kidney damage, hypotension, and bronchospasms

- Other nephrotoxic drugs (such as aminoglycosides): Increased risk of serious renal damage

- Foscarnet, ganciclovir, tenofovir, adefovir: Risk of hematological and renal side effects of amphotericin B are increased

- Transfusion of leukocytes: Risk of pulmonal (lung) damage occurs, space the intervals between the application of amphotericin B and the transfusion, and monitor pulmonary function

Mechanism of action

Amphotericin B binds with ergosterol, a component of fungal cell membranes, forming pores that cause rapid leakage of monovalent ions (K+, Na+, H+ and Cl−) and subsequent fungal cell death. This is amphotericin B's primary effect as an antifungal agent.[29][30] It has been found that the amphotericin B/ergosterol bimolecular complex that maintains these pores is stabilized by Van der Waals interactions.[31] Researchers have found evidence that amphotericin B also causes oxidative stress within the fungal cell,[32] but it remains unclear to what extent this oxidative damage contributes to the drug's effectiveness.[29] The addition of free radical scavengers or antioxidants can lead to amphotericin resistance in some species, such as Scedosporium prolificans, without affecting the cell wall.

Two amphotericins, amphotericin A and amphotericin B, are known, but only B is used clinically, because it is significantly more active in vivo. Amphotericin A is almost identical to amphotericin B (having a C=C double bond between the 27th and 28th carbons), but has little antifungal activity.[33]

Toxicity

Mammalian and fungal membranes both contain sterols, a primary membrane target for amphotericin B. Because mammalian and fungal membranes are similar in structure and composition, this is one mechanism by which amphotericin B causes cellular toxicity. Amphotericin B molecules can form pores in the host membrane as well as the fungal membrane. This impairment in membrane barrier function can have lethal effects.[32][34][35] Ergosterol, the fungal sterol, is more sensitive to amphotericin B than cholesterol, the common mammalian sterol. Reactivity with the membrane is also sterol concentration dependent.[36] Bacteria are not affected as their cell membranes do not contain sterols.

Amphotericin administration is limited by infusion-related toxicity. This is thought to result from innate immune production of proinflammatory cytokines.[34][37]

Biosynthesis

The natural route to synthesis includes polyketide synthase components.[38] The carbon chains of Amphotericin B are assembled from sixteen 'C2' acetate and three 'C3'propionate units by polyketide syntheses (PKSs).[39] Polyketide biosynthesis begins with the decarboxylative condensation of a dicarboxylic acid extender unit with a starter acyl unit to form a β-ketoacyl intermediate. The growing chain is constructed by a series of Claisen reactions. Within each module, the extender units are loaded onto the current ACP domain by acetyl transferase (AT). The ACP-bound elongation group reacts in a Claisen condensation with the KS-bound polyketide chain. Ketoreductase (KR), dehydratase (DH) and enoyl reductase (ER) enzymes may also be present to form alcohol, double bonds or single bonds.[40] After cyclisation, the macrolactone core undergoes further modification by hydroxylation, methylation and glycosylation. The order of these processes is unknown.

File:Biosynthesis of amphotericin B.pdf

History

It was originally extracted from Streptomyces nodosus, a filamentous bacterium, in 1955, at the Squibb Institute for Medical Research from cultures of an undescribed streptomycete isolated from the soil collected in the Orinoco River region of Venezuela.[33] Two antifungal substances were isolated from the soil culture, Amphotericin A and Amphotericin B, but B had better antifungal activity.[41] In 1959, it received its licence for use in localised fungal infections.[42] Its complete stereo structure was determined in 1970 by an X-ray structure of the N-iodoacetyl derivative.[43] The first synthesis of the compound's naturally occurring enantiomeric form was achieved in 1987 by K. C. Nicolaou.[44] For decades it remained the only effective therapy for invasive fungal disease until the development of the azole antifungals in the early 1980s.[41]

Society and culture

Cost and availability

Globally, amphotericin B is not available to over 480 million people.[45] Where it is obtainable the price ranges from <US$1 per day to around $170 per day.[45]

Formulations

It is a subgroup of the macrolide antibiotics, and exhibits similar structural elements.[46] Currently, the drug is available in many forms. Either "conventionally" complexed with sodium deoxycholate (ABD), as a cholesteryl sulfate complex (ABCD), as a lipid complex (ABLC), and as a liposomal formulation (LAMB). The latter formulations have been developed to improve tolerability and decrease toxicity, but may show considerably different pharmacokinetic characteristics compared to conventional amphotericin B.[19]

Intravenous

Amphotericin B alone is insoluble in normal saline at a pH of 7. Therefore, several formulations have been devised to improve its intravenous bioavailability.[33] Lipid-based formulations of amphotericin B are no more effective than conventional formulations, although there is some evidence that lipid-based formulations may be better tolerated by patients and may have fewer adverse effects.[47]

Deoxycholate

The original formulation uses sodium deoxycholate to improve solubility.[19] Amphotericin B deoxycholate (ABD) is administered intravenously.[41] As the original formulation of amphotericin, it is often referred to as "conventional" amphotericin.[48]

Liposomal

In order to improve the tolerability of amphotericin and reduce toxicity, several lipid formulations have been developed.[19] Liposomal formulations have been found to have less renal toxicity than deoxycholate,[49][50] and fewer infusion-related reactions.[19] They are more expensive than amphotericin B deoxycholate.[51]

AmBisome (LAMB) is a liposomal formulation of amphotericin B for injection and consists of a mixture of phosphatidylcholine, cholesterol and distearoyl phosphatidylglycerol that in aqueous media spontaneously arrange into unilamellar vesicles that contain amphotericin B.[19][52]

It was developed by NeXstar Pharmaceuticals (acquired by Gilead Sciences in 1999). It was approved by the FDA in 1997.[53] It is marketed by Gilead in Europe and licensed to Astellas Pharma (formerly Fujisawa Pharmaceuticals) for marketing in the US, and Sumitomo Pharmaceuticals in Japan. Fungisome[54] is a generic liposomal complex of amphotericin B marketed by Lifecare Innovations of India.

Lipid complex formulations

A number of lipid complex preparations are also available. Abelcet was approved by the FDA in 1995.[55] It consists of amphotericin B and two lipids in a 1:1 ratio that form large ribbon-like structures.[19] Amphotec is a complex of amphotericin and sodium cholesteryl sulfate in a 1:1 ratio. Two molecules of each form a tetramer that aggregate into spiral arms on a disk-like complex.[52] It was approved by the FDA in 1996.[55]

By mouth

An oral preparation exists but is not widely available.[56] The amphipathic nature of amphotericin along with its low solubility and permeability has posed major hurdles for oral administration given its low bioavailability. In the past it had been used for fungal infections of the surface of the GI tract such as thrush, but has been replaced by other antifungals such as nystatin and fluconazole.[57]

However, recently novel nanoparticulate drug delivery systems such as AmbiOnp,[58] nanosuspensions, lipid-based drug delivery systems including cochleates, self-emulsifying drug delivery systems,[59] solid lipid nanoparticles[60] and polymeric nanoparticles[61]—such as Amphotericin B in pegylated polylactide coglycolide copolymer nanoparticles[62]—have demonstrated potential for oral formulation of amphotericin B.[63]

Names

Amphotericin name originates from the chemical's amphoteric properties.

Brands include: Halizon,[64] Amphocil, Abelcet,[65] and Fungilin.

Conventional amphotericin B brands include Amphocin and Fungizone.[66] Liposomal brands include Abelcet,[66] Amphotec,[66] Ambisome.[66][67] and Fungisome.[68]

References

- 1 2 3 "AMPHOTERICIN B conventional injectable - Essential drugs". medicalguidelines.msf.org. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Amphotericin B". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2015-01-01. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 19 November 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 World Health Organization (March 2010). Control of the leishmaniasis: report of a meeting of the WHO Expert Committee on the Control of Leishmaniases. Geneva: World Health Organization. pp. 55, 88, 186. hdl:10665/44412. ISBN 9789241209496.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. p. 145. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- ↑ Walker, S. R. (2012). Trends and Changes in Drug Research and Development. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 109. ISBN 9789400926592. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

- ↑ Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 477. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2020-12-10. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ Kendig's disorders of the respiratory tract in children (Ninth ed.). Philadelphia, PA. 2019. pp. 507–527.e3. ISBN 978-0-323-44887-1. Archived from the original on 12 December 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ↑ Drugs Active against Fungi, Pneumocystis, and Microsporidia. pp. 479–494.e4. ISBN 978-1-4557-4801-3.

- ↑ Moen, Marit D.; Lyseng-Williamson, Katherine A.; Scott, Lesley J. (2012-09-17). "Liposomal Amphotericin B". Drugs. 69 (3): 361–392. doi:10.2165/00003495-200969030-00010. ISSN 0012-6667. PMID 19275278.

- ↑ Rura, Nicole (2013-10-29). "Understanding the evolution of drug resistance points to novel strategy for developing better antimicrobials". Archived from the original on 2016-11-15. Retrieved 2016-11-14 – via Whitehead Institute.

- ↑ den Boer, Margriet; Davidson, Robert N. (2006-04-01). "Treatment options for visceral leishmaniasis". Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy. 4 (2): 187–197. doi:10.1586/14787210.4.2.187. ISSN 1744-8336. PMID 16597201.

- ↑ Grace, Eddie; Asbill, Scott; Virga, Kris (November 2015). "Naegleria fowleri: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment Options". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 59 (11): 6677–6681. doi:10.1128/AAC.01293-15. PMC 4604384. PMID 26259797.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Antifungal Agents, Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs" (PDF). 2015-11-16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-06-21. Retrieved 2015-11-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Hamill, Richard J. (2013-06-01). "Amphotericin B Formulations: A Comparative Review of Efficacy and Toxicity". Drugs. 73 (9): 919–934. doi:10.1007/s40265-013-0069-4. ISSN 0012-6667. PMID 23729001.

- 1 2 "Index | The Antimicrobial Index Knowledgebase - TOKU-E". antibiotics.toku-e.com. Archived from the original on 2015-11-09. Retrieved 2015-11-17.

- ↑ "AMPHOTERICIN B liposomal injectable - Essential drugs". medicalguidelines.msf.org. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ↑ "Shake and Bake". TheFreeDictionary.com. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2016-12-09.

- ↑ Hartsel, Scott. "Studies on Amphotericin B" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ Walsh, Thomas J.; Finberg, Robert W.; Arndt, Carola; Hiemenz, John; Schwartz, Cindy; Bodensteiner, David; Pappas, Peter; Seibel, Nita; Greenberg, Richard N. (1999-03-11). "Liposomal Amphotericin B for Empirical Therapy in Patients with Persistent Fever and Neutropenia". New England Journal of Medicine. 340 (10): 764–771. doi:10.1056/NEJM199903113401004. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 10072411.

- ↑ Perfect, John R.; Dismukes, William E.; Dromer, Francoise; Goldman, David L.; Graybill, John R.; Hamill, Richard J.; Harrison, Thomas S.; Larsen, Robert A.; Lortholary, Olivier (2010-02-01). "Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Cryptococcal Disease: 2010 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 50 (3): 291–322. doi:10.1086/649858. ISSN 1058-4838. PMC 5826644. PMID 20047480.

- ↑ Jill Adler-Moore,* and Richard T. liposomal formulation, structure, mechanism of action and pre-clinical experience. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (2002) 49, 21–30

- ↑ J. Czub, M. Baginski. Amphotericin B and Its New Derivatives Mode of action. Department of pharmaceutical Technology and Biochemistry. Faculty of Chemistry, Gdnsk University of Technology. 2009, 10-459-469.

- ↑ Zietse, R.; Zoutendijk, R.; Hoorn, E. J. (2009). "Fluid, electrolyte and acid–base disorders associated with antibiotic therapy". Nature Reviews Nephrology. 5 (4): 193–202. doi:10.1038/nrneph.2009.17. PMID 19322184.

- 1 2 Mesa-Arango, Ana Cecilia; Scorzoni, Liliana; Zaragoza, Oscar (2012-01-01). "It only takes one to do many jobs: Amphotericin B as antifungal and immunomodulatory drug". Frontiers in Microbiology. 3: 286. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2012.00286. PMC 3441194. PMID 23024638.

- ↑ O'Keeffe, Joseph; Doyle, Sean; Kavanagh, Kevin (2003-12-01). "Exposure of the yeast Candida albicans to the anti-neoplastic agent adriamycin increases the tolerance to amphotericin B". Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 55 (12): 1629–1633. doi:10.1211/0022357022359. ISSN 2042-7158. PMID 14738588.

- ↑ "Molecular modelling of amphotericin B-ergosterol primary complex in water II". Biophysical Chemistry. 141.

- 1 2 Baginski, M.; Czub, J. (2009). "Amphotericin B and Its New Derivatives–Mode of Action". Current Drug Metabolism. 10 (5): 459–69. doi:10.2174/138920009788898019. PMID 19689243.

- 1 2 3 Dutcher, James D. (1968-10-01). "THe discovery and development of amphotericin b". Chest. 54 (Supplement_1): 296–298. doi:10.1378/chest.54.Supplement_1.296. ISSN 0012-3692. PMID 4877964.

- 1 2 Laniado-Laborin R. and Cabrales-Vargas MN. Amphotericin B: side effects and toxicity. Revista Iberoamericana de Micologia. (2009): 223–7.

- ↑ Pfizer. Amphocin. Accessed at "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-04-19. Retrieved 2010-02-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) on Feb 18 2010. - ↑ Vertut-Croquin, Aline; Bolard, Jacques; Chabbert, Marie; Gary-Bobo, Claude (1983). "Differences in the Interaction of the Polyene Antibiotic Amphotericin B with Cholesterol- or Ergosterol-Containing Phospholipid Vesicles. A Circular Dichroism and Permeability Study". Biochemistry. 22 (12): 2939–2944. doi:10.1021/bi00281a024. PMID 6871175.

- ↑ Drew, R. Pharmacology of amphotericin B. Uptodate. Sep 2009. Accessed at http://www.utdol.com/online/content/topic.do?topicKey=antibiot/4619&selectedTitle=2~150&source=search_result%5B%5D on Feb 18 2010.

- ↑ Khan N, Rawlings B, Caffrey P (2011-01-26). "A labile point in mutant amphotericin polyketide synthases". Biotechnol. Lett. 33 (6): 1121–6. doi:10.1007/s10529-011-0538-3. PMID 21267757. Archived from the original on 2020-07-28. Retrieved 2019-01-08.

- ↑ McNamara, Carmel M.; Box, Stephen; Crawforth, James M.; Hickman, Benjamin S.; Norwood, Timothy J. (1998-01-01). "Biosynthesis of amphotericin B" (PDF). Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 1 (1): 83–88. doi:10.1039/A704545J. hdl:2381/33805. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-09-21. Retrieved 2018-05-16.

- ↑ Caffrey, Patrick; Lynch, Susan; Flood, Elizabeth; Finnan, Shirley; Oliynyk, Markiyan (2001). "Amphotericin biosynthesis in Streptomyces nodosus: deductions from analysis of polyketide synthase and late genes". Chemistry & Biology. 8 (7): 713–723. doi:10.1016/S1074-5521(01)00046-1. PMID 11451671.

- 1 2 3 Maertens, J. A. (2004-03-01). "History of the development of azole derivatives". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 10: 1–10. doi:10.1111/j.1470-9465.2004.00841.x. ISSN 1469-0691. PMID 14748798.

- ↑ Cavassin, Francelise B.; Baú-Carneiro, João Luiz; Vilas-Boas, Rogério R.; Queiroz-Telles, Flávio (March 2021). "Sixty years of Amphotericin B: An Overview of the Main Antifungal Agent Used to Treat Invasive Fungal Infections". Infectious Diseases and Therapy. 10 (1): 115–147. doi:10.1007/s40121-020-00382-7. ISSN 2193-8229. PMID 33523419. Archived from the original on 2021-08-27. Retrieved 2021-06-06.

- ↑ McNamara, Carmel M.; Box, Stephen; Crawforth, James M.; Hickman, Benjamin S.; Norwood, Timothy J.; Rawlings, Bernard J. (1998). "Biosynthesis of amphotericin B". Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 1. 0 (1): 83–88. doi:10.1039/a704545j. hdl:2381/33805.

- ↑ Nicolaou, K. C.; Daines, R. A.; Chakraborty, T. K.; Ogawa, Y. (1987-04-01). "Total synthesis of amphotericin B". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 109 (9): 2821–2822. doi:10.1021/ja00243a043. ISSN 0002-7863.

- 1 2 Tudela, Juan Luis Rodríguez; Denning, David W. (1 November 2017). "Recovery from serious fungal infections should be realisable for everyone". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 17 (11): 1111–1113. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30319-5. ISSN 1473-3099. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ↑ "Chemistry and Biology of the Polyene Macrolide Antibiotics". Bacteriological Reviews. 32.

- ↑ Steimbach, Laiza M., Fernanda S. Tonin, Suzane Virtuoso, Helena HL Borba, Andréia CC Sanches, Astrid Wiens, Fernando Fernandez‐Llimós, and Roberto Pontarolo. "Efficacy and safety of amphotericin B lipid‐based formulations—A systematic review and meta‐analysis." Mycoses 60, no. 3 (2017): 146-154.

- ↑ Clemons, KV; Stevens, DA (April 1998). "Comparison of Fungizone, Amphotec, AmBisome, and Abelcet for Treatment of Systemic Murine Cryptococcosis". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 42 (4): 899–902. doi:10.1128/AAC.42.4.899. PMC 105563. PMID 9559804.

- ↑ Botero Aguirre, Juan Pablo; Restrepo Hamid, Alejandra Maria (2015-11-23). "Amphotericin B deoxycholate versus liposomal amphotericin B: Effects on kidney function". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD010481. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010481.pub2. PMID 26595825.

- ↑ Mistro, Sóstenes; Maciel, Isis de M.; Menezes, Rouseli G. de; Maia, Zuinara P.; Schooley, Robert T.; Badaró, Roberto (2012-06-15). "Does Lipid Emulsion Reduce Amphotericin B Nephrotoxicity? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 54 (12): 1774–1777. doi:10.1093/cid/cis290. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 22491505.

- ↑ Bennett, John (2000-11-15). "Editorial Response: Choosing Amphotericin B Formulations—Between a Rock and a Hard Place". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 31 (5): 1164–1165. doi:10.1086/317443. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 11073746.

- 1 2 Slain, Douglas (1999-03-01). "Lipid-Based Amphotericin B for the Treatment of Fungal Infections". Pharmacotherapy. 19 (3): 306–323. doi:10.1592/phco.19.4.306.30934. ISSN 1875-9114. PMID 10221369.

- ↑ "Drug Approval Package". www.accessdata.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-11-17. Retrieved 2015-11-03.

- ↑ "Untitled Document". www.fungisome.com. Archived from the original on 2015-12-27. Retrieved 2015-11-03.

- 1 2 "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products". www.accessdata.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 2014-08-13. Retrieved 2015-11-03.

- ↑ Wasan KM, Wasan EK, Gershkovich P, et al. (2009). "Highly Effective oral amphotericin B formulation against murine visceral leishmaniasis". J Infect Dis. 200 (3): 357–360. doi:10.1086/600105. PMID 19545212.

- ↑ Pappas, Peter G.; Kauffman, Carol A.; Andes, David; Benjamin, Daniel K.; Calandra, Thierry F.; Edwards, John E.; Filler, Scott G.; Fisher, John F.; Kullberg, Bart-Jan (2009-03-01). "Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 48 (5): 503–535. doi:10.1086/596757. ISSN 1537-6591. PMID 19191635.

- ↑ Patel, Pratikkumar A.; Patravale, Vandana B. (2011). "AmbiOnp: solid lipid nanoparticles of amphotericin B for oral administration". Journal of Biomedical Nanotechnology. 7 (5): 632–639. doi:10.1166/jbn.2011.1332. PMID 22195480.

- ↑ Wasan, EK; Bartlett, K; Gershkovich, P; Sivak, O; Banno, B; Wong, Z; Gagnon, J; Gates, B; Leon, CG; Wasan, KM (2009). "Development and characterization of oral lipid-based amphotericin B formulations with enhanced drug solubility, stability and antifungal activity in rats infected with Aspergillus fumigatus or Candida albicans". International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 372 (1–2): 76–84. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.01.003. PMID 19236839.

- ↑ Patel, PA; Patravale, VB (2011). "AmbiOnp: solid lipid nanoparticles of amphotericin B for oral administration". Journal of Biomedical Nanotechnology. 7 (5): 632–639. doi:10.1166/jbn.2011.1332. PMID 22195480.

- ↑ Italia, JL; Yahya, MM; Singh, D (2009). "Biodegradable nanoparticles improve oral Bioavailability of Amphotericin B and Show Reduced Nephrotoxicity Compared to Intravenous Fungizone®". Pharmaceutical Research. 26 (6): 1324–1331. doi:10.1007/s11095-009-9841-2. PMID 19214716.

- ↑ AL-Quadeib, Bushra T.; Radwan, Mahasen A.; Siller, Lidija; Horrocks, Benjamin; Wright, Matthew C. (2015-07-01). "Stealth Amphotericin B nanoparticles for oral drug delivery: In vitro optimization". Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal. 23 (3): 290–302. doi:10.1016/j.jsps.2014.11.004. PMC 4475820. PMID 26106277.

- ↑ Patel PA, Fernandes CB, Pol AS, Patravale VB. Oral Amphotericin B: Challenges and avenues. Int. J. Pharm. Biosci. Technol. 2013;1(1):1–9

- ↑ "Halizon". Edu.drugs. Archived from the original on 15 November 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ↑ Cuddihy, Grace; Wasan, Ellen K.; Di, Yunyun; Wasan, Kishor M. (26 February 2019). "The Development of Oral Amphotericin B to Treat Systemic Fungal and Parasitic Infections: Has the Myth Been Finally Realized?". Pharmaceutics. 11 (3). doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics11030099. ISSN 1999-4923. PMID 30813569. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Cohen, Michael Richard (2007). Medication Errors. American Pharmacist Associan. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-58212-092-8. Archived from the original on 2021-08-27. Retrieved 2021-06-06.

- ↑ "AmBisome Liposomal 50 mg Powder for dispersion for infusion - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (emc)". www.medicines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 14 May 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ↑ Dorlo, Thomas P. C.; Balasegaram, Manica (2014-08-01). "Different liposomal amphotericin B formulations for visceral leishmaniasis". The Lancet Global Health. 2 (8): e449. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70252-9. ISSN 2214-109X. Archived from the original on 2021-08-27. Retrieved 2021-06-06.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|

- "Amphotericin B". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2020-12-10. Retrieved 2020-01-12.

- AmBisome Summaries of Product Characteristics (United Kingdom) Archived 2020-11-20 at the Wayback Machine

- Amphotericin B Archived 2020-10-25 at the Wayback Machine

- "Amphotericin B Liposomal Injection". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 2020-12-10. Retrieved 2020-01-12.

- "Amphotericin B Lipid Complex Injection". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 2020-12-10. Retrieved 2020-01-12.