Amiodarone

Amiodarone is an antiarrhythmic medication used to treat and prevent a number of types of cardiac dysrhythmias.[4] This includes ventricular tachycardia (VT), ventricular fibrillation (VF), and wide complex tachycardia, as well as atrial fibrillation and paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia.[4] Evidence in cardiac arrest, however, is poor.[5] It can be given by mouth, intravenously, or intraosseously.[4] When used by mouth, it can take a few weeks for effects to begin.[4]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌæmiˈoʊdəroʊn/ or /əˈmiːoʊdəˌroʊn/ |

| Trade names | Cordarone, Nexterone, Pacerone, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a687009 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous, intraosseous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 20–55% |

| Protein binding | 96% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 58 d (range 15–142 d) |

| Excretion | Primarily liver and bile |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.016.157 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C25H29I2NO3 |

| Molar mass | 645.320 g·mol−1 |

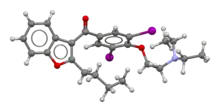

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Common side effects include feeling tired, tremor, nausea, and constipation.[4] As amiodarone can have serious side effects, it is mainly recommended only for significant ventricular arrhythmias.[4] Serious side effects include lung toxicity such as interstitial pneumonitis, liver problems, heart arrhythmias, vision problems, thyroid problems, and death.[4] If taken during pregnancy or breastfeeding it can cause problems in the fetus.[4] It is a class III antiarrhythmic medication.[4] It works partly by increasing the time before a heart cell can contract again.[4]

Amiodarone was first made in 1961 and came into medical use in 1962 for chest pain believed to be related to the heart.[6] It was pulled from the market in 1967 due to side effects.[7] In 1974 it was found to be useful for arrhythmias and reintroduced.[7] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[8] It is available as a generic medication.[4] In 2019, it was the 183rd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 3 million prescriptions.[9][10]

Medical uses

Amiodarone has been used both in the treatment of acute life-threatening arrhythmias as well as the long term suppression of arrhythmias. It is used both in supraventricular arrhythmias and ventricular arrhythmias.

Cardiac arrest

Defibrillation is the treatment of choice for ventricular fibrillation and pulseless ventricular tachycardia resulting in cardiac arrest. While amiodarone has been used in shock-refractory cases, evidence of benefit is poor.[5] Amiodarone does not appear to improve survival or positive outcomes in those who had a cardiac arrest.[11]

Ventricular tachycardia

Amiodarone may be used in the treatment of ventricular tachycardia in certain instances. Individuals with hemodynamically unstable ventricular tachycardia should not initially receive amiodarone. These individuals should be cardioverted.

Amiodarone can be used in individuals with hemodynamically stable ventricular tachycardia. In these cases, amiodarone can be used regardless of the individual's underlying heart function and the type of ventricular tachycardia; it can be used in individuals with monomorphic ventricular tachycardia, but is contraindicated in individuals with polymorphic ventricular tachycardia as it is associated with a prolonged QT interval which will be made worse with anti-arrhythmic drugs.[12]

Atrial fibrillation

Individuals who have undergone open heart surgery are at an increased risk of developing atrial fibrillation (or AF) in the first few days post-procedure. In the ARCH trial, intravenous amiodarone (2 g administered over 2 d) has been shown to reduce the incidence of atrial fibrillation after open heart surgery when compared to placebo.[13] However, clinical studies have failed to demonstrate long-term efficacy and have shown potentially fatal side effects such as pulmonary toxicities. While amiodarone is not approved for AF by the FDA, it is a commonly prescribed off-label treatment due to the lack of equally effective treatment alternatives.

So-called 'acute onset atrial fibrillation', defined by the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology (NASPE) in 2003, responds well to short duration treatment with amiodarone. This has been demonstrated in seventeen randomized controlled trials, of which five included a placebo arm. The incidence of severe side effects in this group is low.

The benefit of amiodarone in the treatment of atrial fibrillation in the critical care population has yet to be determined but it may prove to be the agent of choice where the patient is hemodynamically unstable and unsuitable for DC cardioversion. It is recommended in such a role by the UK government's National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE).

Contraindications

Women who are pregnant or may become pregnant are strongly advised to not take amiodarone. Since amiodarone can be expressed in breast milk, women taking amiodarone are advised to stop nursing.

It is contraindicated in individuals with sinus nodal bradycardia, atrioventricular block, and second or third degree heart block who do not have an artificial pacemaker.

Individuals with baseline depressed lung function should be monitored closely if amiodarone therapy is to be initiated.

Formulations of amiodarone that contain benzyl alcohol should not be given to neonates, because the benzyl alcohol may cause the potentially fatal "gasping syndrome".[14]

Amiodarone can worsen the cardiac arrhythmia brought on by digitalis toxicity.

Side effects

At oral doses of 400 mg per day or higher, amiodarone can have serious, varied side effects, including toxicity to thyroid, liver, lung, and retinal functions, requiring clinical surveillance and regular laboratory testing.[15][16] Allergic reactions to amiodarone may occur.[15] Most individuals administered amiodarone on a chronic basis will experience at least one side effect.[16] In some people, daily use of amiodarone at 100 mg oral doses can be effective for arrhythmia control with no or minimal side effects.[16]

Lung

Side effects of oral amiodarone at doses of 400 mg or higher include various pulmonary effects.[17] The most serious reaction is interstitial lung disease. Risk factors include high cumulative dose, more than 400 milligrams per day, duration over two months, increased age, and preexisting pulmonary disease. Some individuals were noted to develop pulmonary fibrosis after a week of treatment, while others did not develop it after years of continuous use.[17] Common practice is to avoid the agent if possible in individuals with decreased lung function.

The most specific test of pulmonary toxicity due to amiodarone is a dramatically decreased DLCO noted on pulmonary function testing.

Thyroid

Induced abnormalities in thyroid function are common.[15] Both under- and overactivity of the thyroid may occur.

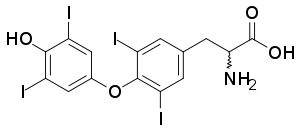

Amiodarone is structurally similar to thyroxine and also contains iodine. Both of these contribute to the effects of amiodarone on thyroid function.[18][19] Amiodarone also causes an anti-thyroid action, via Plummer and Wolff–Chaikoff effects, due its large amount of iodine in its molecule, which causes a particular "cardiac hypothyroidism" with bradycardia and arrhythmia.[20][21]

Thyroid function should be checked at least every six months.[22]

- Hypothyroidism (slowing of the thyroid) occurs frequently; in the SAFE trial, which compared amiodarone with other medications for the treatment of atrial fibrillation, biochemical hypothyroidism (as defined by a TSH level of 4.5–10 mU/L) occurred in 25.8% of the amiodarone-treated group as opposed to 6.6% of the control group (taking placebo or sotalol). Overt hypothyroidism (defined as TSH >10 mU/L) occurred at 5.0% compared to 0.3%; most of these (>90%) were detected within the first six months of amiodarone treatment.[23]

- Amiodarone induced thyrotoxicosis (AIT), can be caused due to the high iodine contebt in the drug via the Jod-Basedow effect. This is known as Type 1 AIT, and usually occurs in patients with an underlying predisposition to hyperthyroidism such as Graves' disease, within weeks to months after starting amiodarone. Type 1 AIT is usually treated with anti-thyroid drugs or thyroidectomy. Type 2 AIT is caused by a destructive thyroiditis due to a direct toxic effect of amiodarone on thyroid follicular epithelial cells. Type 2 AIT can occur even years after starting amiodarone, is usually self-limited and responds to anti-inflammatory treatment such as corticosteroids.[24] In practice, often the type of AIT is undetermined or presumed as mixed with both treatments combined.[24] Thyroid uptake measurements (I-123 or I-131), which are used to differentiate causes of hyperthyroidism, are generally unreliable in patients who have been taking amiodarone. Because of the high iodine content of amiodarone, the thyroid gland is effectively saturated, thus preventing further uptake of isotopes of iodine. However, a positive radioactive iodine can be used to rule in type 1AIT .

Amiodarone

Amiodarone Thyroxine

Thyroxine

Eye

Corneal micro-deposits (cornea verticillata,[25] also called vortex or whorl keratopathy) are almost universally present (over 90%) in individuals taking amiodarone longer than 6 months, especially doses greater than 400 mg/day. These deposits typically do not cause any symptoms. About 1 in 10 individuals may complain of a bluish halo. Anterior subcapsular lens deposits are relatively common (50%) in higher doses (greater than 600 mg/day) after 6 months of treatment. Optic neuropathy, nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (N-AION), occurs in 1–2% of people and is not dosage dependent.[26] Bilateral optic disc swelling and mild and reversible visual field defects can also occur. Loss of eyelashes has been linked to amiodarone use.[27]

Liver

Abnormal liver enzyme results are common in people taking amiodarone.[15] Much rarer are jaundice, hepatomegaly (liver enlargement), and hepatitis (inflammation of the liver).[28]

Low-dose amiodarone has been reported to cause pseudo-alcoholic cirrhosis.[29][30]

Skin

Long-term administration of amiodarone (usually more than eighteen months) is associated with a light-sensitive blue-grey discoloration of the skin, sometimes called ceruloderma; such patients should avoid exposure to the sun and use sunscreen that protects against ultraviolet-A and -B. The discoloration will slowly improve upon cessation of the medication, however, the skin color may not return completely.[31]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Use during pregnancy may result in a number of problems in the infant including thyroid problems, heart problems, neurological problems, and preterm birth.[32] Use during breastfeeding is generally not recommended though one dose may be okay.[32]

Other

Long-term use of amiodarone has been associated with peripheral neuropathies.[33]

Amiodarone is sometimes responsible for epididymitis. Amiodarone accumulates in the head of the organ and can cause unilateral or bilateral inflammation. It tends to resolve if amiodarone is stopped.[34]

Some cases of gynecomastia have been reported with men on amiodarone.[35]

A study published in 2013 showed a possible association between amiodarone and an increased risk of cancer, especially in males, with a dose-dependent effect.[36]

Interactions

The pharmacokinetics of numerous drugs, including many that are commonly administered to individuals with heart disease, are affected by amiodarone. Particularly, doses of digoxin should be halved in individuals taking amiodarone. Amiodarone may also interact with sotalol.[37]

Amiodarone potentiates the action of warfarin by inhibiting the clearance of both (S) and (R) warfarin. Individuals taking both of these medications should have their warfarin doses adjusted based on their dosing of amiodarone, and have their anticoagulation status (measured as prothrombin time (PT) and international normalized ratio (INR)) measured more frequently. Dose reduction of warfarin is as follows: 40% reduction if amiodarone dose is 400 mg daily, 35% reduction if amiodarone dose is 300 mg daily, 30% reduction if amiodarone dose is 200 mg daily, and 25% reduction if amiodarone dose is 100 mg daily. The effect of amiodarone on the warfarin concentrations can be as early as a few days after initiation of treatment; however, the interaction may not peak for up to seven weeks.

Amiodarone inhibits the action of the cytochrome P450 isozyme family. This reduces the clearance of many drugs, including the following:

In 2015, Gilead Sciences warned health care providers about people that began taking the hepatitis C drugs ledipasvir/sofosbuvir or sofosbuvir along with amiodarone, who developed abnormally slow heartbeats or died of cardiac arrest.[38]

Metabolism

Amiodarone is extensively metabolized in the liver by cytochrome P450 3A4 and can affect the metabolism of numerous other drugs. It interacts with digoxin, warfarin, phenytoin, and others. The major metabolite of amiodarone is desethylamiodarone (DEA), which also has antiarrhythmic properties. The metabolism of amiodarone is inhibited by grapefruit juice, leading to elevated serum levels of amiodarone.

On 8 August 2008, the FDA issued a warning of the risk of rhabdomyolysis, which can lead to kidney failure or death, when simvastatin is used with amiodarone. This interaction is dose-dependent with simvastatin doses exceeding 20 mg. This drug combination especially with higher doses of simvastatin should be avoided.[39]

Excretion

Excretion is primarily via the liver and the bile duct with almost no elimination via the kidney and it is not dialyzable.[1] Elimination half-life average of 58 days (ranging from 25 to 100 days [Remington: The Science and Practice of Pharmacy 21st edition]) for amiodarone and 36 days for the active metabolite, desethylamiodarone (DEA).[1] There is 10-50% transfer of amiodarone and DEA in the placenta as well as a presence in breast milk.[1] Accumulation of amiodarone and DEA occurs in adipose tissue and highly perfused organs (i.e. liver, lungs),[1] therefore, if an individual was taking amiodarone on a chronic basis, if it is stopped it will remain in the system for weeks to months.[1]

Pharmacology

Amiodarone is categorized as a class III antiarrhythmic agent, and prolongs phase 3 of the cardiac action potential, the repolarization phase where there is normally decreased calcium permeability and increased potassium permeability. It has numerous other effects, however, including actions that are similar to those of antiarrhythmic classes Ia, II, and IV.

Amiodarone is a blocker of voltage gated potassium (KCNH2) and voltage gated calcium channels (CACNA2D2).[40]

Amiodarone slows conduction rate and prolongs the refractory period of the SA and AV nodes.[41] It also prolongs the refractory periods of the ventricles, bundles of His, and the Purkinje fibres without exhibiting any effects on the conduction rate.[41] Amiodarone has been shown to prolong the myocardial cell action potential duration and refractory period and is a non-competitive β-adrenergic inhibitor.[42]

It also shows beta blocker-like and calcium channel blocker-like actions on the SA and AV nodes, increases the refractory period via sodium- and potassium-channel effects, and slows intra-cardiac conduction of the cardiac action potential, via sodium-channel effects. It is suggested that amiodarone may also exacerbate the phenotype associated with Long QT-3 syndrome causing mutations such as ∆KPQ. This effect is due to a combination of blocking the peak sodium current, but also contributing to an increased persistent sodium current.[43]

Amiodarone chemically resembles thyroxine (thyroid hormone), and its binding to the nuclear thyroid receptor might contribute to some of its pharmacologic and toxic actions.[44]

History

The original observation that amiodarone's progenitor molecule, khellin, had cardioactive properties, was made by the Russian physiologist Gleb von Anrep while working in Cairo in 1946.[45] Khellin is obtained from a plant extract of Khella or Ammi visnaga, a common plant in north Africa. Anrep noticed that one of his technicians had been cured of anginal symptoms after taking khellin, then used for various, non-cardiac ailments. This led to efforts by European pharmaceutical industries to isolate an active compound. Amiodarone was initially developed in 1961 at the Labaz company, Belgium, by chemists Tondeur and Binon, who were working on preparations derived from khellin. It became popular in Europe as a treatment for angina pectoris.[46][47]

As a doctoral candidate at Oxford University, Bramah Singh determined that amiodarone and sotalol had antiarrhythmic properties and belonged to a new class of antiarrhythmic agents (what would become the class III antiarrhythmic agents).[48] Today the mechanisms of action of amiodarone and sotalol have been investigated in more detail. Both drugs have been demonstrated to prolong the duration of the action potential, prolonging the refractory period, by interacting among other cellular function with K+ channels.

Based on Singh's work, the Argentinian physician Mauricio Rosenbaum began using amiodarone to treat his patients who have supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias, with impressive results. Based on papers written by Rosenbaum developing Singh's theories, physicians in the United States began prescribing amiodarone to their patients with potentially life-threatening arrhythmias in the late 1970s.[49][50] By 1980, amiodarone was commonly prescribed throughout Europe for the treatment of arrhythmias, but in the U.S. amiodarone remained unapproved by the Food and Drug Administration, and physicians were forced to directly obtain amiodarone from pharmaceutical companies in Canada and Europe.

The FDA was reluctant to officially approve the use of amiodarone since initial reports had shown increased incidence of serious pulmonary side-effects of the drug. In the mid-1980s, the European pharmaceutical companies began putting pressure on the FDA to approve amiodarone by threatening to cut the supply to American physicians if it was not approved. In December 1985, amiodarone was approved by the FDA for the treatment of arrhythmias.[2][51] This makes amiodarone one of the few drugs approved by the FDA without rigorous randomized clinical trials.

Name

Amiodarone may be an acronym for its IUPAC name (2-butyl-1-benzofuran-3-yl)-[4-[2-(diethylamino)ethoxy]-3,5-diiodophenyl]methanone,[52] where ar is a placeholder for phenyl. This is partially supported by dronedarone which is noniodinated benzofuran derivative of amiodarone, where the arylmethanone is conserved.

Dosing

Amiodarone is available in oral and intravenous formulations.

Orally, it is available under the brand names Pacerone (produced by Upsher-Smith Laboratories, Inc.) and Cordarone (produced by Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories).[1][2] It is also available under the brand name Aratac (produced by Alphapharm Pty Ltd) in Australia and New Zealand, and further in Australia under the brands Cardinorm and Rithmik as well as a number of generic brands. Also Arycor in South Africa (Produced by Winthrop Pharmaceuticals.). In South America, it is known as Atlansil and is produced by Roemmers.

In India, amiodarone is marketed (produced by Cipla Pharmaceutical) under the brand name Tachyra. It is also available in intravenous ampules and vials.

The dose of amiodarone administered is tailored to the individual and the dysrhythmia that is being treated. When administered orally, the bioavailability of amiodarone is quite variable. Absorption ranges from 22 to 95%, with better absorption when it is given with food.[53]

Administration

Amiodarone IV should be administered via a central venous catheter. It has a pH of 4.08. If administered outside of the standard concentration of 900 mg/500mL it should be administered using a 0.22 micron filter to prevent precipitate from reaching the patient. Amiodarone IV is a known vesicant. For infusions of longer than 1 hour, concentrations of 2 mg/mL should not be exceeded unless a central venous catheter is used.[54]

References

- "Pacerone- amiodarone hydrochloride tablet". DailyMed. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- "Cordarone (amiodarone) tablets, for oral use Initial U.S. Approval: 1985". DailyMed. 30 October 2018. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- "Nexterone- Amiodarone HCl injection, solution". DailyMed. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- "Amiodarone Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 19 September 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- Ali, MU; Fitzpatrick-Lewis, D; Kenny, M; Raina, P; Atkins, DL; Soar, J; Nolan, J; Ristagno, G; Sherifali, D (1 September 2018). "Effectiveness of antiarrhythmic drugs for shockable cardiac arrest: A systematic review" (PDF). Resuscitation. 132: 63–72. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.08.025. PMID 30179691. S2CID 52154562.

- Analytical Profiles of Drug Substances and Excipients. Academic Press. 1992. p. 4. ISBN 9780080861159. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Fischer, Janos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2005). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 12. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- "The Top 300 of 2019". ClinCalc. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- "Amiodarone – Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- Laina, A; Karlis, G; Liakos, A; Georgiopoulos, G; Oikonomou, D; Kouskouni, E; Chalkias, A; Xanthos, T (9 July 2016). "Amiodarone and cardiac arrest: Systematic review and meta-analysis". International Journal of Cardiology. 221: 780–788. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.07.138. PMID 27434349.

- Resuscitation Council (UK) Peri-arrest arrhythmias – Tachycardia algorithm Archived 3 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 25 January 2016

- Guarnieri T, Nolan S, Gottlieb SO, Dudek A, Lowry DR (1999). "Intravenous amiodarone for the prevention of atrial fibrillation after open heart surgery: the Amiodarone Reduction in Coronary Heart (ARCH) trial". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 34 (2): 343–347. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00212-0. PMID 10440143.

- Centers for Disease Control, (CDC) (11 June 1982). "Neonatal deaths associated with use of benzyl alcohol – United States". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 31 (22): 290–291. PMID 6810084. Archived from the original on 30 August 2012.

- "Amiodarone". Drugs.com. 18 May 2022. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- Chokesuwattanaskul, Ronpichai; Shah, Nupur; Chokesuwattanaskul, Susama; Liu, Zhigang; Thakur, Ranjan (1 April 2020). "Low-dose Amiodarone Is Safe: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". The Journal of Innovations in Cardiac Rhythm Management. 11 (4): 4054–4061. doi:10.19102/icrm.2020.110403. ISSN 2156-3977. PMC 7192149. PMID 32368381.

- "Amiodarone Side Effects". Drugs.com. 25 April 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- Lombardi A, Inabnet WB, Owen R, Farenholtz KE, Tomer Y (January 2015). "Endoplasmic reticulum stress as a novel mechanism in amiodarone-induced destructive thyroiditis". J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 100 (1): e1–10. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-2745. PMC 4283007. PMID 25295624.

- Hall, George M.; Hunter, Jennifer M.; Cooper, Mark S. (2010). Core Topics in Endocrinology in Anaesthesia and Critical Care. Cambridge University Press. p. 170. ISBN 9781139486125. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Venturi, Sebastiano (2011). "Evolutionary Significance of Iodine". Current Chemical Biology. 5 (3): 155–162. doi:10.2174/187231311796765012. ISSN 1872-3136.

- Venturi, Sebastiano (2014). "Iodine, PUFAs and Iodolipids in Health and Disease: An Evolutionary Perspective". Human Evolution. 29 (1–3): 185–205. ISSN 0393-9375.

- Bartalena, Luigi; Bogazzi, Fausto; Chiovato, Luca; Hubalewska-Dydejczyk, Alicja; Links, Thera P.; Vanderpump, Mark (2018). "2018 European Thyroid Association (ETA) Guidelines for the Management of Amiodarone-Associated Thyroid Dysfunction". European Thyroid Journal. 7 (2): 55–66. doi:10.1159/000486957. PMC 5869486. PMID 29594056.

- Batcher EL, Tang XC, Singh BN, Singh SN, Reda DJ, Hershman JM (October 2007). "Thyroid function abnormalities during amiodarone therapy for persistent atrial fibrillation". Am J Med. 120 (10): 880–885. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.04.022. PMID 17904459.

- Ylli, Dorina; Wartofsky, Leonard; Burman, Kenneth D (1 January 2021). "Evaluation and Treatment of Amiodarone-Induced Thyroid Disorders". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 106 (1): 226–236. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa686. PMID 33159436. S2CID 226275566.

- Chew, E; Ghosh; M. McCulloch, C. (June 1982). "Amiodarone-induced cornea verticillata". Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology. 17 (3): 96–99. PMID 7116220.

- Passman RS, Bennett CL, Purpura JM, Kapur R, et al. (2012). "Amiodarone-associated Optic Neuropathy: A Critical Review". Am J Med. 125 (5): 447–453. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.09.020. PMC 3322295. PMID 22385784.

- Roy, Frederick Hampton (2012). Ocular differential diagnosis (9th ed.). Panama City, Panama: Jaypee Highlights Medical Publishers. p. 94. ISBN 9789350255711. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Flaharty KK, Chase SL, Yaghsezian HM, Rubin R (1989). "Hepatotoxicity associated with amiodarone therapy". Pharmacotherapy. 9 (1): 39–44. doi:10.1002/j.1875-9114.1989.tb04102.x. PMID 2646621. S2CID 37972060.

- Singhal A, Ghosh P, Khan SA (2003). "Low dose amiodarone causing pseudo-alcoholic cirrhosis". Age and Ageing. 32 (2): 224–225. doi:10.1093/ageing/32.2.224. PMID 12615569.

- Puli SR, Fraley MA, Puli V, Kuperman AB, Alpert MA (2005). "Hepatic cirrhosis caused by low-dose oral amiodarone therapy". Am. J. Med. Sci. 330 (5): 257–261. doi:10.1097/00000441-200511000-00012. PMID 16284489.

- Murphy, Robert P.; Canavan, Michelle (16 January 2020). "Skin Discoloration from Amiodarone". New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (3): e5. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm1906774. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 31940702. S2CID 210333420.

- "Amiodarone Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Drugs.com. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- A G Fraser; I N McQueen; A H Watt; M R Stephens (June 1985). "Peripheral neuropathy during longterm high-dose amiodarone therapy". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 48 (6): 576–578. doi:10.1136/jnnp.48.6.576. PMC 1028375. PMID 2989436.

- Thomas A, Woodard C, Rovner ES, Wein AJ (February 2003). "Urologic complications of nonurologic medications". Urol. Clin. North Am. 30 (1): 123–131. doi:10.1016/S0094-0143(02)00111-8. PMID 12580564.

- Gynecomastia: Its features, and when and how to treat it

- Vincent Yi-Fong Su; Yu-Wen Hu; Kun-Ta Chou; et al. (April 2013). "Amiodarone and the risk of cancer". Cancer. 119 (8): 1699–1705. doi:10.1002/cncr.27881. PMID 23568847. S2CID 24144312.

- "Amiodarone and sotalol Drug Interactions". Drugs.com. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- West, Stephen. "Gilead Warns After Hepatitis Patient on Heart Drug Dies" Archived 22 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Published 21 March 2015.

- "Information on Simvastatin/Amiodarone". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 21 September 2008. Retrieved 21 September 2008.

- "Amiodarone". Drugbank. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- Harris, Luke; Williams, Romeo Roncucci, eds. (1986). Amiodarone: pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, toxicology, clinical effects. Paris: Médecine et sciences internationales. p. 12. ISBN 2864391252.

- "FDA Drug Label". Archived from the original on 27 March 2017.

- Ghovanloo MR, Abdelsayed M, Ruben PC (2016). "Effects of amiodarone and N-desethylamiodarone on cardiac voltage-gated sodium channels". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 7: 11. doi:10.3389/fphar.2016.00039. PMC 4771766. PMID 26973526.

- Brunton, Laurence L.; Lazo, John S.; Parker, Keith, eds. (2005). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-142280-3.

- Anrep GV, Barsoum GS (1946). "Ammi visnaga in the treatment of the anginal syndrome". Br Heart J. 8 (4): 171–177. doi:10.1136/hrt.8.4.171. PMC 503580. PMID 18610042.

- Deltour G, Binon F, Tondeur R, et al. (1962). "[Studies in the benzofuran series. VI. Coronary-dilating activity of alkylated and aminoalkylated derivatives of 3-benzoylbenzofuran.]". Archives Internationales de Pharmacodynamie et de Thérapie (in French). 139: 247–254. PMID 14026835.

- Charlier R, Deltour G, Tondeur R, Binon F (1962). "[Studies in the benzofuran series. VII. Preliminary pharmacological study of 2-butyl-3-(3,5-diiodo-4-beta-N-diethylaminoethoxybenzoyl)-benzofuran.]". Archives Internationales de Pharmacodynamie et de Thérapie (in French). 139: 255–264. PMID 14020244.

- Singh BN, Vaughan Williams EM (1970). "The effect of amiodarone, a new anti-anginal drug, on cardiac muscle". Br. J. Pharmacol. 39 (4): 657–667. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1970.tb09891.x. PMC 1702721. PMID 5485142.

- Rosenbaum MB, Chiale PA, Halpern MS, et al. (1976). "Clinical efficacy of amiodarone as an antiarrhythmic agent". Am. J. Cardiol. 38 (7): 934–944. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(76)90807-9. PMID 793369.

- Rosenbaum MB, Chiale PA, Haedo A, Lázzari JO, Elizari MV (1983). "Ten years of experience with amiodarone". Am. Heart J. 106 (4 Pt 2): 957–964. doi:10.1016/0002-8703(83)90022-4. PMID 6613843.

- "Drug Approval Package: Cordarone (Amiodarone Hydrochloride) Tablets. NDA #018972". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- "Compound summary for CID 2157". pubchem.ncbi.nil.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016.

- Siddoway LA (2003). "Amiodarone: guidelines for use and monitoring". American Family Physician. 68 (11): 2189–2196. PMID 14677664. Archived from the original on 15 May 2008.

- Infusion Nurses Society Task Force, Gorskey; et al. (January–February 2017). "Development of an Evidence-Based List of Noncytotoxic Vesicant Medications and Solutions". Journal of Infusion Nurses Society. 40 (1): 26–40. doi:10.1097/NAN.0000000000000202. PMID 28030480. S2CID 32460457.

Further reading

- Siddoway LA (December 2003). "Amiodarone: guidelines for use and monitoring". Am Fam Physician. 68 (11): 2189–2196. PMID 14677664. Archived from the original on 15 May 2008. Retrieved 16 May 2004.