Cyproterone

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | SH-80881; SH-881; NSC-758636; 1α,2α-Methylene-6-chloro-17α-hydroxy-δ6-progesterone; 1α,2α-Methylene-6-chloro-17α-hydroxypregna-4,6-diene-3,20-dione |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, topical |

| Drug class | Steroidal antiandrogen |

| ATC code | |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.218.313 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

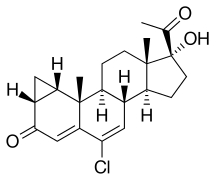

| Formula | C22H27ClO3 |

| Molar mass | 374.91 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Cyproterone, also known by its developmental code name SH-80881, is a steroidal antiandrogen which was studied in the 1960s and 1970s but was never introduced for medical use.[1][2][3] It is an analogue of cyproterone acetate (CPA), an antiandrogen, progestin, and antigonadotropin which was introduced instead of cyproterone and is widely used as a medication.[1][2] Cyproterone and CPA were among the first antiandrogens to be developed.[4]

It is important to clarify that the term cyproterone is often used as a synonym and shorthand for cyproterone acetate, and when the term occurs, what is almost always being referred to is, confusingly, CPA and not actually cyproterone. Cyproterone itself, unlike CPA, was never introduced for medical use and hence is not available as a medication.

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Antiandrogenic activity

Cyproterone is a potent antiandrogen, similarly to CPA.[5][6] However, it has approximately three-fold lower potency as an antagonist of the androgen receptor (AR) relative to CPA.[6] Like CPA, cyproterone is actually a weak partial agonist of the AR, and hence has the potential for both antiandrogenic and androgenic activity in some contexts.[7] Unlike CPA (which is a highly potent progestogen), cyproterone is a pure antiandrogen[3] and is virtually devoid of progestogenic activity.[8][9][10][11] As such, it is not an antigonadotropin, and is actually progonadotropic in males, increasing gonadotropin and testosterone levels due to inhibition of AR-mediated negative feedback on the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis.[5][11][12]

Due to its progonadotropic effects in males, unlike CPA, cyproterone has been found, in male rodents, to increase testicular weight, increase the total number of type A spermatogonia, increase the total number of Sertoli cells,[13] hyperstimulate the Leydig cells, and to have almost no effect on spermatogenesis. Conversely, it has also been reported for male rodents that spermiogenesis is inhibited and that accessory sexual gland weights (e.g., prostate gland, seminal vesicles) and fertility were markedly reduced, although with rapid recovery from the changes upon cessation of treatment.[12] In any case, the medication is said to not be an effective antispermatogenic agent, whereas CPA is effective.[14] Also unlike CPA, due to its lack of progestogenic and antigonadotropic activity, cyproterone does not suppress ovulation in women.[3][15]

Other activities

Both CPA and, to a smaller extent, cyproterone possess some weak glucocorticoid activity and suppress adrenal gland and spleen weight in animals, with CPA having about one-fifth the potency of prednisone in mice.[8][16] Unlike CPA, cyproterone seems to show some inhibition of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase and 5α-reductase in vitro.[6] In contrast to CPA, cyproterone shows no affinity for opioid receptors.[17]

Chemistry

Cyproterone, also known as 1α,2α-methylene-6-chloro-17α-hydroxy-δ6-progesterone or as 1α,2α-methylene-6-chloro-17α-hydroxypregna-4,6-diene-3,20-dione, is a synthetic pregnane steroid and a derivative of progesterone.[1][2] It is the free alcohol or 17α-deacetylated analogue of CPA.[1][2]

History

Cyproterone, along with CPA, was first patented in 1962,[18] with subsequent patents in 1963 and 1965.[1] It was studied clinically between 1967 and 1972.[19][20] Unlike CPA, the medication was never marketed for medical use.[1][2] Cyproterone was the first pure antiandrogen to be developed,[21] with other closely following examples of this class including the steroidal antiandrogens benorterone and BOMT and the nonsteroidal antiandrogen flutamide.[4]

Society and culture

Generic names

Cyproterone is the generic name of the drug and its INN.[1][2] It is also known by the developmental code names SH-80881 and SH-881.[1][2]

Research

In clinical studies, cyproterone was found to be far less potent and effective as an antiandrogen than CPA, likely in significant part due to its lack of concomitant antigonadotropic action.[3] Cyproterone was studied as a treatment for precocious puberty by Bierich (1970, 1971), but no significant improvement was observed.[22] In men, 100 mg/day cyproterone proved to be rather ineffective in treating acne, which was hypothesized to be related to its progonadotropic effects in males and counteraction of its antiandrogen activity.[3][23] In women however, who have much lower levels of testosterone and in whom the medication has no progonadotropic activity, 100 to 200 mg/day oral cyproterone was effective in reducing sebum production in all patients as early as 2 to 4 weeks following the start of treatment.[3] In contrast, topical cyproterone was far less effective and barely outperformed placebo.[3]

Another study showed disappointing results with 100 mg/day cyproterone for reducing sebum production in women with hyperandrogenism.[3] Similarly, the medication showed disappointing results in the treatment of hirsutism in women, with a distinct hair reduction occurring in only a limited percentage of cases.[3] In the same study, the reduction of acne was better, but was clearly inferior to that produced by CPA, and only the improvement in seborrhea was regarded as satisfactory.[3] The addition of an oral contraceptive to cyproterone resulted in a somewhat better improvement in acne and seborrhea relative to cyproterone alone.[3] According to Jacobs (1979), "[cyproterone] proved to be without clinical value for reasons that cannot be discussed here."[24] In any case, cyproterone has been well tolerated by patients in dosages of up to 300 mg/day.[3]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 339–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis US. 2000. p. 289. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Constantin E. Orfanos; Rudolf Happle (1990). Hair and Hair Diseases. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 1197–. ISBN 978-3-642-74612-3.

- 1 2 Schröder, Fritz H.; Radlmaier, Albert (2009). "Steroidal Antiandrogens". In V. Craig Jordan; Barrington J. A. Furr (eds.). Hormone Therapy in Breast and Prostate Cancer. Humana Press. pp. 325–346. doi:10.1007/978-1-59259-152-7_15. ISBN 978-1-60761-471-5.

The progestational effect [of CPA] is linked to the presence of the acetyl group at position C17 of the steroid. Consequently, the free alcohol of CPA, cyproterone, which lacks the acetyl group, is devoid of progestational properties. However, it still exerts antiandrogenic activity, although less pronounced than CPA. Consequently, cyproterone was the first compound falling into the nowadays well-known class of pure antiandrogens.

- 1 2 Moltz, L.; Römmler, A.; Schwartz, U.; Hammerstein, J. (1978). "Effects of Cyproterone Acetate (CPA) on Pituitary Gonadotrophin Release and on Androgen Secretion Before and After LH-RH Double Stimulation Tests in Men". International Journal of Andrology. 1 (s2b): 713–719. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2605.1978.tb00518.x. ISSN 0105-6263.

[...] Hammerstein 1977). This consideration is based on the fact that free cyproterone is a potent anti- androgen without antigonadotrophic activity and causes, therefore, an in- crease in gonadotrophins and in androgens (Graf et al. 1974). In [...]

- 1 2 3 Giorgi EP, Shirley IM, Grant JK, Stewart JC (1973). "Androgen dynamics in vitro in the human prostate gland. Effect of cyproterone and cyproterone acetate". Biochem. J. 132 (3): 465–74. doi:10.1042/bj1320465. PMC 1177610. PMID 4125095.

Cyproterone (6-chloro-17-hydroxy-1,2α-methylenepregna-4,6-diene-3,20-dione) and cyproterone acetate (17-acetoxy-6-chloro-1,2α-methylene-pregna-4,6-diene-3,20-dione) are powerful anti-androgens, which exert multiple actions in many species. Cyproterone acetate has three times the anti-androgenic potency of cyproterone, and also has some progestational properties (for review, see Neumann et al., 1970). [...] Cyproterone seemed to decrease the activity of 17α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase and of 5α-steroid reductase in human prostate in vitro, as it does in testes and liver of rats (Breuer & Hoffmann, 1967; Hoffmann & Breuer, 1968; Denef et al., 1968). Cyproterone acetate did not seem to have any direct effect on the activity of these two enzymes.

- ↑ Charles H. Sawyer; Roger A. Gorski (1971). Steroid Hormones and Brain Function. University of California Press. pp. 366–. ISBN 978-0-520-01887-7.

- 1 2 A. Hughes; S. H. Hasan; G. W. Oertel; H. E. Voss; F. Bahner; F. Neumann; H. Steinbeck; K.-J. Gräf; J. Brotherton; H. J. Horn; R. K. Wagner (27 November 2013). Androgens II and Antiandrogens / Androgene II und Antiandrogene. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 279–. ISBN 978-3-642-80859-3.

The only chemical difference between cyproterone and cyproterone acetate consists of a free or esterified hydroxyl group at C17 but this difference accounts for profound differences in the mechanism of action and possibilities for use in the intact organism. Both steroids are highly active antiandrogens at any route of administration, the acetate has a greater antiandrogenic potency than the free alcohol. With the exception of a slight depressive effect on the adrenals, cyproterone does not have other side-activities unrelated to antiandrogenicity. It has, therefore, been termed "pure antiandrogen". Cyproterone acetate has one major additional activity: it is one of the strongest gestagens that have ever been synthesized [23, 70, 32, 77], [...]

- ↑ Hammerstein, J. (1981). "Antiandrogens — Basic Concepts for Treatment". Hair Research. pp. 330–335. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-81650-5_49. ISBN 978-3-642-81652-9.

Contrary to benorterone, free cyproterone, and flutamide, CPA is not a pure anti- androgen. In fact, it is one of the most potent progestogens known and, in comparison to that potency, it is a relatively weak antiandrogen and a still weaker anti- gonadotropin.

- ↑ Spona, J.; Schneider, W. H. F.; Bieglmayer, Ch.; Schroeder, R.; Pirker, R. (1979). "Ovulation Inhibition with Different Doses of Levonorgestrel and Other Progestogens: Clinical and Experimental Investigations". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 58 (s88): 7–15. doi:10.3109/00016347909157223. ISSN 0001-6349. PMID 393050. S2CID 30486799.

Cyproterone which has a very weak biological progestogen potency exhibited low affinity for the progestogen-receptor (Table I).

- 1 2 A. Labhart (6 December 2012). Clinical Endocrinology: Theory and Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 473–. ISBN 978-3-642-96158-8.

Cyproterone acetate is 250 and 3330 times as potent a progestational agent as progesterone and cyproterone alcohol (10< respectively (Clauberg assay). [...] The pure anti-androgens, such as cyproteron, block the receptors of the negative feedback system. An uninhibited secretion of the releasing factors and an increased production of gonadotropins results, so that the inhibitory effect on the endorgans may finally be overcome by overpoduction of testosterone (Neumann, 1971). Cyproterone acetate, however, with its marked progestational effect, inhibits the release of LH and FSH at the same time and thus has a lasting anti-androgenic effect (Neumann, 1970). Thus, cyproteron leads to an increase in LH, whereas cyproteron acetate inhibits both LH and FSH.

- 1 2 Steinbeck H, Mehring M, Neumann F (1971). "Comparison of the effects of cyproterone, cyproterone acetate and oestradiol on testicular function, accessory sexual glands and fertility in a long-term study on rats". J. Reprod. Fertil. 26 (1): 65–76. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0260065. PMID 5091295.

- ↑ Viguier-Martinez M.C.; Hochereau De Reviers M.T. (1977). "Comparative action of cyproterone and cyproterone acetate on pituitary and plasma gonadotropin levels, the male genital tract and spermatogenesis in the growing rat" (PDF). Annales de Biologie Animale, Biochimie, Biophysique. 17 (6): 1069–1076. doi:10.1051/rnd:19770814.

- ↑ Ewing, L L; Robaire, B (1978). "Endogenous Antispermatogenic Agents: Prospects for Male Contraception". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 18 (1): 167–187. doi:10.1146/annurev.pa.18.040178.001123. ISSN 0362-1642. PMID 206192.

Cyproterone (6-chloro-17a-hydroxy-1a,2a-methylene-pregna-4,6-diene-3,20-dione) and cyproterone acetate have received considerable attention as antispermatogenic substances. Cyproterone, which has·only weak antigonadotropic properties, was found to be a poor antispermatogenic agent (42). In contrast, cyproterone acetate, which inhibits gonadotropin secretion, was found to be an antispermatogenic agent (142).

- ↑ Stewart, Mary Ellen; Pochi, Peter E. (1978). "Antiandrogens and the Skin". International Journal of Dermatology. 17 (3): 167–179. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1978.tb06057.x. ISSN 0011-9059. PMID 148431. S2CID 43649686.

While CPA alone probably suppresses ovulation, cyproterone, which possesses no progestational activity, does not!8,72

- ↑ Broulik PD, Starka L (1975). "Corticosteroid-like effect of cyproterone and cyproterone acetate in mice". Experientia. 31 (11): 1364–5. doi:10.1007/bf01945829. PMID 1204803. S2CID 11452300.

- ↑ Gutiérrez M, Menéndez L, Brieva R, Hidalgo A, Baamonde A (1998). "Different types of steroids inhibit [3H]diprenorphine binding in mouse brain membranes". Gen. Pharmacol. 31 (5): 747–51. doi:10.1016/s0306-3623(98)00110-4. PMID 9809473.

- ↑ U.S. Patent 3,234,093

- ↑ Apostolakis, M.; Tamm, J.; Voigt, K.-D. (1967). "Biochemical and Clinical Studies with Cyproterone". European Journal of Endocrinology. 56 (1 Suppl): S56. doi:10.1530/acta.0.056S056. ISSN 0804-4643.

- ↑ Walsh PC, Swerdloff RS, Odell WD (1972). "Cyproterone: effect on serum gonadotropins in the male". Endocrinology. 90 (6): 1655–9. doi:10.1210/endo-90-6-1655. PMID 5020316.

- ↑ Craig, Jordan V.; Furr, B.J.A. (5 February 2010). Hormone Therapy in Breast and Prostate Cancer. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 326–. ISBN 978-1-59259-152-7.

- ↑ Rager K, Huenges R, Gupta D, Bierich JR (1973). "The treatment of precocious puberty with cyproterone acetate". Acta Endocrinol. 74 (2): 399–408. doi:10.1530/acta.0.0740399. PMID 4270254.

Free cyproterone was first tried as a therapy for precocious puberty by Bierich (1970, 1971). The results, however, did not show any significant improvement.

- ↑ Gerhard Raspé (1969). Schering Workshop on Steroid Metabolism: "in vitro versus in vivo.". Pergamon Press. ISBN 9780080175447.

[...] In this investigation a number of normal male volunteers were treated for three weeks with 100 mg free cyproterone per day. Sebum production was measured by the Straufi-Pochi method before treatment and on the 7th, 10th, 11th, 15th, 18th, [...]

- ↑ Howard S. Jacobs; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (Great Britain) (1979). Advances in gynaecological endocrinology: proceedings of the Sixth Study Group of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 18th and 19th October, 1978. The College. p. 367. ISBN 978-0-87489-225-3.

Limited clinical experience also exists with benorterone, the first anti-androgen tried in man, and with free cyproterone. In the late sixties benorterone was reported to give promising results in 93 androgenized women but was soon withdrawn from clinical trial, mainly because of the development of gynaecomastia in the male. As a big advantage compared with CPA, it was found to be effective not only orally but also topically. Free cyproterone, on the other hand, proved to be without clinical value for reasons that cannot be discussed here. Thus we are left with CPA as the only anti-androgen that is already on the market in several countries.

Further reading

- A. Hughes; S. H. Hasan; G. W. Oertel; H. E. Voss; F. Bahner; F. Neumann; H. Steinbeck; K.-J. Gräf; J. Brotherton; H. J. Horn; R. K. Wagner (27 November 2013). Androgens II and Antiandrogens / Androgene II und Antiandrogene. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 241–545. ISBN 978-3-642-80859-3.