Alfaxalone

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Alfaxan |

| Other names | Alphaxalone; Alphaxolone; Alfaxolone; 3α-Hydroxy-5α-pregnane-11,20-dione; PHAX-001; Phaxan, Alphaxalone (BAN UK) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| License data | |

| Drug class | |

| ATCvet code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 30–50% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Metabolites |

|

| Elimination half-life |

|

| Excretion | Mostly renal |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.164.405 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H32O3 |

| Molar mass | 332.484 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Alfaxalone, also known as alphaxalone or alphaxolone and sold under the brand name Alfaxan, is a neuroactive steroid and general anesthetic which is used currently in veterinary practice as an induction agent for anesthesia and as an injectable anesthetic.[1][2][3] Though it is more expensive than other induction agents,[4] it often preferred due to the lack of depressive effects on the cardiovascular system. The most common side effect seen in current veterinary practice is respiratory depression when Alfaxan is administered concurrently with other sedative and anesthetic drugs; when premedications aren't given, veterinary patients also become agitated and hypersensitive when waking up.

Alfaxalone works as a positive allosteric modulator on GABAA receptors and, at high concentrations, as a direct agonist of the GABAA receptor. It is cleared quickly by the liver, giving it a relatively short terminal half-life and preventing it from accumulating in the body, lowering the chance of overdose.

Veterinary use

Alfaxalone is used as an induction agent, an injectable anesthetic, and a sedative in animals.[5] While it is commonly used in cats and dogs, it has also been successfully used in rabbits,[6] horses, sheep, pigs, and exotics such as red-eared turtles, axolotl, green iguanas, marmosets,[7] and koi fish.[8] As an induction agent, alfaxalone causes the animal to relax enough to be intubated, which then allows the administration of inhalational anesthesia. Premedication (administering sedative drugs prior to induction) increases the potency of alfaxalone as an induction agent.[7] Alfaxalone can be used instead of gas anesthetics in surgeries that are under 30 minutes, where it is given at a constant rate via IV (constant rate infusion); this is especially useful in procedures such as bronchoscopies or repairing tracheal tears, as there is no endotracheal tube in the way.[4][9] Once the administration of alfaxalone stops, the animal quickly recovers from anesthesia.[10]

Alfaxalone can be used as a sedative when given intramuscularly (IM), though this requires a larger volume (and not all countries allow alfaxalone to be administered IM).[11][12]

Despite its use as an anesthetic, alfaxalone itself has no analgesic properties.[7]

Available forms

Though alfaxalone is not licensed for IM or subcutaneous use in the United States (as both cause longer recoveries with greater agitation and hypersensitivity to stimuli), it is routinely used IM in cats, and is licensed as such in other countries.[4][13]

Alfaxalone is dissolved in 2-hydroxylpropyl-β cyclodextrin (which is toxic to people).[14] The cyclodextrin is a large, starch-derived molecule with a hydrophobic core where alfaxalone stays, allowing the mixture to be dissolved in water and sold as an aqueous solution. They act as one unit, and only dissociate once in vivo.[11][15]

Specific populations

Alfaxalone has been used to perform c-sections in pregnant cats; though it crosses the placental barrier and had some effects on the kittens, there is no respiratory depression and no lasting effect. Alfaxalone has also been found to be safe in young puppies and kittens.[16][17]

Alfaxalone has been noted to be a good anesthetic agent for dogs with ventricular arrhythmias and for sighthounds.[13][18]

Side effects

Alfaxalone has relatively few side effects compared to other anesthetics; most notable is its lack of cardiovascular depression at clinical doses, which makes it unique among anesthetics.[10][13] The most common side effect is respiratory depression: in addition to apnea, the most prevalent, alfaxalone can also decrease the respiratory rate, minute volume, and oxygen saturation in the blood.[17] Alfaxalone should be administered slowly over a period of at least 60 seconds or until anesthesia is induced, as quick administration increases the risk of apnea.[5][13] Alfaxalone has some depressive effects on the central nervous system, including a reduction in cerebral blood flow, intracranial pressure, and body temperature.[17]

Greyhounds, who are particularly susceptible to anesthetic side effects, can have decreased blood flow and oxygen supply to the liver.[17]

When no premedications are used, alfaxalone causes animals (especially cats) to be agitated when recovering.[4][13] Dogs and cats will paddle in the air, vocalize excessively, may remain rigid or twitch, and have exaggerated reactions to external stimuli such as light and noise. For this reason, it is recommended that animals recovering from anesthesia by alfaxalone stay in a quiet, dark area.[17]

Overdose

The quick metabolism and elimination of alfaxalone from the body decreases the chance of overdose.[10] It would take over 28 times the normal dose to cause toxicity in cats.[11] Such doses, however, can cause low blood pressure, apnea, hypoxia, and arrhythmia (caused by the apnea and hypoxia).[11]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Alfaxalone is a neuroactive steroid derived from progesterone, though it has no glucocorticoid or mineralocorticoid action.[4][10] Instead, it works by acting on GABAA receptors.[19] It binds to the M3/M4 domains of the α subunit and allosterically modifies the receptor to facilitate the movement of chloride ions into the cell, resulting in hyperpolarization of the post-synaptic nerve (which inhibits actions potentials). At concentrations over 1 micromolar,[20] alfaxalone binds to a site at the interface between the α and β subunits (near the actual GABA binding site) and acts as a GABA agonist, similar to benzodiazepines.[17][21] Alfaxalone, however, does not share the benzodiazepine binding site,[22] and actually prefers different GABAA receptors than benzodiazepenes do. It works best on the α1-β2-γ2-L isoform.[11] Research suggests that neuroactive steroids increase the expression of GABAA receptors, making it more difficult to build tolerance.[21]

Pharmacokinetics

Alfaxalone is metabolized quickly and does not accumulate in the body; its use as an induction agent thus doesn't increase the time needed to recover from anesthesia.[4][10] If it administered more slowly by diluting it in sterile water, less actual alfaxalone is needed.[9] Alfaxalone binds to 30–50% of plasma proteins,[23] and has a terminal half-life of 25 minutes in dogs and 45 minutes in cats when given at clinical doses (2 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg respectively). The pharmacokinetics are nonlinear in cats and dogs.[14][24]

Most alfaxalone metabolism takes place in the liver, though some takes place in the lungs and kidneys as well.[24] In the liver, it undergoes both phase I (cytochrome P450-dependent) and phase II (conjugation-dependent) metabolism. The phase I products are the same in cats and dogs: allopregnatrione, 3β-alfaxalone, 20-hydroxy-3β-alfaxalone, 2-hydroxyalfaxalone, and 2α-hydroxyalfaxalone.[11][17] In dogs, the phase II metabolites are alfaxalone glucuronide (the major metabolite), 20-hydroxyalfaxalone sulfate, and 2α-hydroxyalfaxalone glucuronid. In cats, there is a greater production of 20-hydroxyalfaxalone sulfate than alfaxalone glucuronide; cats also have 3β-alfaxalone-sulfate, which is not present in dogs.[11][17]

Alfaxalone is mostly excreted in the urine, though some is excreted in the bile as well.

Chemistry

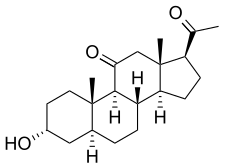

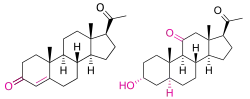

Alfaxalone, also known as 11-oxo-3α,5α-tetrahydroprogesterone, 5α-pregnan-3α-ol-11,20-dione, or 3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnane-11,20-dione, is a synthetic pregnane steroid and a derivative of progesterone.[1] It is specifically a modification of progesterone in which the C3 ketone has been reduced to a hydroxyl group, the double bond between the C4 and C5 positions has been reduced and is now a single bond, and a ketone has been substituted at the C11 position.[1] Alfaxalone is also a derivative of allopregnanolone, differing from it only by the addition of the C11 ketone.[1] Other closely related steroids include ganaxolone, hydroxydione, minaxolone, pregnanolone, and renanolone.[1]

History

In 1941, progesterone and 5β-pregnanedione were discovered to have CNS depressant effects in rodents. This began a search to make a synthetic steroid that could be used as an anesthetic. Most of these efforts were aimed at making alfaxalone more water-soluble.[21]

In 1971, a combination of alfaxalone and alfadolone acetate was released as the anesthetics Althesin (for human use) and Saffan (for veterinary use).[7][24] The two were dissolved in Cremophor EL: a polyoxyelthylated castor oil surfactant.[14]

Althesin was removed from the market in 1984 for causing anaphylaxis; it was later found that this was due to Cremphor EL, which caused the body to release histamine, rather than alfaxolone or alfadolone.[7][13][21] Saffan was removed from use for dogs only, but stayed on for other animals, none of which histamine release to the same extant that dogs did.[25] It was still especially valued in cats for its lack of depressant effects on the cardiovascular system, which made it three times less fatal than any other anesthetic on the market at the time.[7][9] The release of histamine caused most cats (70%) to have edema and hyperemia in their ears and paws;[26] only some also got laryngeal or pulmonary edema.[25]

In 1999, a lyophilized form of alfaxalone was released for cats.[11] The new drug, Alfaxan, used a cyclodextrin as a carrier agent to make alfaxalone more water-soluble rather than Camphor EL.[13] Alfadolone was not included in the mixture, as its hypnotic effects were quite weak.[25] An aqueous form of Alfaxan was released in Australia in 2000–2001, and Saffan was finally removed from the market in 2002. Alfaxan was released in the UK in 2007, central Europe in 2008, Canada in 2011, and the United States in 2012.[11][12]

Currently, a human form of alfaxalone is in development under the name "Phaxan": alfaxalone will be dissolved in 7-sulfo-butyl-ether-β-cyclodextrin, which, unlike the cyclodextrin used in Alfaxan, is not toxic to people.[14]

Society and culture

Generic names

Alfaxalone is the INN, BAN, DCF, and JAN of alfaxolone. Alphaxalone was the former BAN of the drug,[1][2] but this was eventually changed. Alphaxolone and alfaxolone are additional alternative spellings.[1][2][3][27]

Brand names

Alfaxalone was marketed in 1971 in combination with alfadolone acetate under the brand name Althesin for human use and Saffan for veterinary use.[17][28] Althesin was withdrawn from the market in 1984, whereas Saffan remained marketed.[29] A new formulation containing alfaxalone only was introduced for veterinary use in 1999 under the brand name Alfaxan.[17][28] Following the introduction of Alfaxan, Saffan was gradually discontinued and is now no longer marketed.[29][30] Another new formulation containing alfaxalone alone is currently under development for use in humans with the tentative brand name Phaxan.[14][31]

Availability

Alfaxalone is marketed for veterinary use under the brand name Alfaxan in a number of countries, including Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Ireland, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Taiwan, the United Kingdom, and the United States.[3][32][33]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Elks J (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 664–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- 1 2 3 Morton IK, Hall JM (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 11. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1.

- 1 2 3 "Alfaxalone". Drugs.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Rezende M (June 2015). "Reintroduced Anesthetic Alfaxalone" (PDF). Clinician's Brief. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 23, 2015. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- 1 2 US National Library of Medicine. "ALFAXAN- alfaxalone injection, solution". DailyMed. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- ↑ Varga M (2014). "Chapter 4: Anaesthesia and Analgesia". Textbook of Rabbit Medicine (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 178–202. ISBN 9780702049798.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Clarke KW, Trim CM, Hall LW, eds. (2014). "Chapter 6: General pharmacology of the injectable agents used in anaesthesia". Veterinary Anaesthesia (11th ed.). Oxford: W.B. Saunders. pp. 135–153. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7020-2793-2.00006-2. ISBN 9780702027932.

- ↑ Minter LJ, Bailey KM, Harms CA, Lewbart GA, Posner LP (July 2014). "The efficacy of alfaxalone for immersion anesthesia in koi carp (Cyprinus carpio)". Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia. 41 (4): 398–405. doi:10.1111/vaa.12113. PMID 24754530.

- 1 2 3 Clarke KW, Trim CM, Hall LW, eds. (2014). "Chapter 16: Anaesthesia of the cat". Veterinary Anaesthesia (11th ed.). Oxford: W.B. Saunders. pp. 499–534. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7020-2793-2.00016-5. ISBN 9780702027932.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ferré PJ, Pasloske K, Whittem T, Ranasinghe MG, Li Q, Lefebvre HP (July 2006). "Plasma pharmacokinetics of alfaxalone in dogs after an intravenous bolus of Alfaxan-CD RTU". Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia. 33 (4): 229–36. doi:10.1111/j.1467-2995.2005.00264.x. PMID 16764587.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Warne LN, Beths T, Whittem T, Carter JE, Bauquier SH (February 2015). "A review of the pharmacology and clinical application of alfaxalone in cats". Veterinary Journal. 203 (2): 141–8. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.12.011. PMID 25582797.

- 1 2 Zeltzman P (November 17, 2014). "Why Administering Alfaxalone Requires A Bit of Education". Veterinary Practice News. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Nieuwendijk H (March 2011). "Alfaxalone". Veterinary Anesthesia & Analgesia Support Group. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Absalom AR, Mason KP (March 1, 2017). Total Intravenous Anesthesia and Target Controlled Infusions: A Comprehensive Global Anthology. Springer. pp. 31, 306. ISBN 9783319476094.

- ↑ Klöppel H, Leece EA (January 2011). "Comparison of ketamine and alfaxalone for induction and maintenance of anaesthesia in ponies undergoing castration". Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia. 38 (1): 37–43. doi:10.1111/j.1467-2995.2010.00584.x. PMID 21214708.

- ↑ Bourne W (2014). "Chapter 19: Anaesthesia for obstetrics". In Clarke KW, Trim CM, Hall LW (eds.). Veterinary Anaesthesia. Canadian Medical Association Journal. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). Oxford: W.B. Saunders. pp. 587–598. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7020-2793-2.00019-0. ISBN 9780702027932. PMC 1707545. PMID 20315061.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Grimm KA, Lamont LA, Tranquilli WJ, Greene SA, Robertson SA (2015). Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia (5th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 289–290. ISBN 9781118526200.

- ↑ Clarke KW, Trim CM, Hall LW, eds. (2014). "Chapter 15: Anaesthesia of the dog". Veterinary Anaesthesia (11th ed.). Oxford: W.B. Saunders. pp. 135–153. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7020-2793-2.00015-3. ISBN 9780702027932.

- ↑ Harrison NL, Vicini S, Barker JL (February 1987). "A steroid anesthetic prolongs inhibitory postsynaptic currents in cultured rat hippocampal neurons". The Journal of Neuroscience. 7 (2): 604–9. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-02-00604.1987. PMC 6568915. PMID 3819824.

- ↑ Visser SA, Smulders CJ, Reijers BP, Van der Graaf PH, Peletier LA, Danhof M (September 2002). "Mechanism-based pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling of concentration-dependent hysteresis and biphasic electroencephalogram effects of alphaxalone in rats". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 302 (3): 1158–67. doi:10.1124/jpet.302.3.1158. PMID 12183676.

- 1 2 3 4 Martinez-Botella G, Ackley MA, Salituro FG, Doherty JJ (January 1, 2014). Natural and Synthetic Neuroactive Steroid Modulators of GABAA and NMDA Receptors. Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry. Vol. 49. pp. 27–42. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800167-7.00003-1. ISBN 9780128003725. ISSN 0065-7743.

- ↑ Mihic SJ, Whiting PJ, Klein RL, Wafford KA, Harris RA (December 1994). "A single amino acid of the human gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor gamma 2 subunit determines benzodiazepine efficacy" (PDF). The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 269 (52): 32768–73. PMID 7806498.

- ↑ Maddison JE, Page SW, Church D, eds. (2008). "Alphaxalone (±alphadolone)". Small Animal Clinical Pharmacology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 101–103. ISBN 9780702028588.

- 1 2 3 Suarez MA, Dzikiti BT, Stegmann FG, Hartman M (May 2012). "Comparison of alfaxalone and propofol administered as total intravenous anaesthesia for ovariohysterectomy in dogs". Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia. 39 (3): 236–44. doi:10.1111/j.1467-2995.2011.00700.x. PMID 22405473.

- 1 2 3 Welsh L (May 8, 2013). Anaesthesia for Veterinary Nurses. John Wiley & Sons. p. 153. ISBN 9781118693148.

- ↑ Liao P (August 2016). Anesthetic and Cardio-pulmonary Effects of Propofol or Alfaxalone with or without Midazolam Co-Induction in Fentanyl Sedated Dogs (PDF) (DVM). Guelph, Ontario: University of Guelph.

- ↑ "Substance Name: Alfaxalone [INN:BAN:DCF:JAN]". ChemIDplus. US National Library of Medicine.

- 1 2 Papich MG (October 2015). Saunders Handbook of Veterinary Drugs: Small and Large Animal. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-323-24485-5.

- 1 2 Clarke KW, Trim CM (28 June 2013). Veterinary Anaesthesia E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-7020-5423-5.

- ↑ Fish RE (2008). Anesthesia and Analgesia in Laboratory Animals. Academic Press. pp. 315–. ISBN 978-0-12-373898-1.

- ↑ "Alfaxalone (PHAX-001; Phaxan)". AdisInsight. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ Official website of Alfaxan

- ↑ Tamura J, Ishizuka T, Fukui S, Oyama N, Kawase K, Miyoshi K, et al. (March 2015). "The pharmacological effects of the anesthetic alfaxalone after intramuscular administration to dogs". The Journal of Veterinary Medical Science. 77 (3): 289–96. doi:10.1292/jvms.14-0368. PMC 4383774. PMID 25428797.

[Alfaxalone] is approved in some countries (e.g., Australia, New Zealand, Europe, Korea, Japan, USA and Canada) as an IV anesthetic agent in dogs and cats.