Dexmedetomidine

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Precedex, Dexdor, Dexdomitor, Sileo, others |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | α2-adrenergic agonist[1] |

| Main uses | Procedural sedation, sedation in the ICU[1] |

| Side effects | Low blood pressure, nausea, dry mouth, abnormal heart rate[1] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | Intravenous infusion, transmucosal, intranasal |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Protein binding | 94% |

| Metabolism | Near complete liver metabolism to inactive metabolites |

| Elimination half-life | 2 hours |

| Excretion | Urinary |

| Chemical and physical data | |

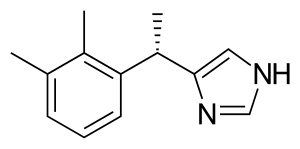

| Formula | C13H16N2 |

| Molar mass | 200.285 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Dexmedetomidine, sold under the trade name Precedex among others, is a medication used for procedural sedation or sedation in the intensive care unit.[1] It results in mild to moderate sedation without much effect on breathing.[1] It is used by intravenous infusion.[1] Onset of effects may take 25 minutes.[2]

Common side effects include low blood pressure, nausea, dry mouth, and an abnormal heart rate.[1] Other side effects may include agitation, high blood sugar, increased body temperature, and decreased breathing.[3] It works by blocking the α2-adrenergic receptors present in certain parts of the brain.[4]

Dexmedetomidine was approved for medical use in the United States in 1999 and Europe in 2011.[1][5] It is available as a generic medication.[3] In the United Kingdom a 1 mg vial costs about £78 as of 2020.[3] Veterinarians may use it for similar purposes in other animals.[6]

Medical uses

Sedation

Dexmedetomidine is most often used in the intensive care setting for light to moderate sedation. It is not recommended for long-term deep sedation. A feature of dexmedetomidine is that it has analgesic properties in addition to its role as a hypnotic, but is opioid sparing; thus, it is not associated with significant respiratory depression (unlike propofol).

Many studies suggest dexmedetomidine for sedation in mechanically ventilated adults may reduce time to extubation and ICU stay.[7][8] People on dexmedetomidine can be rousable and cooperative, a benefit in some procedures.

Compared with other sedatives, some studies suggest dexmedetomidine may be associated with less delirium.[9] However, this finding is not consistent across multiple studies.[8] At the very least, when aggregating many study results together, use of dexmedetomidine appears to be associated with less neurocognitive dysfunction compared to other sedatives.[10] Whether this observation has a beneficial psychological impact is unclear.[9]

Procedural sedation

Dexmedetomidine can also be used for procedural sedation such as during colonoscopy.[11] It can be used as an adjunct with other sedatives like benzodiazepines, opioids, and propofol to enhance sedation and help maintain hemodynamic stability by decreasing the requirement of other sedatives.[12][13] Dexmedetomidine is also used for procedural sedation in children.[14]

There is weak evidence that it can be used for sedation required for awake fibreoptic nasal intubation in patients with a difficult airway.[15]

Other

Dexmedetomidine may be useful for the treatment of the negative cardiovascular effects of acute amphetamines and cocaine intoxication and overdose.[16][17] Dexmedetomidine has also been used as an adjunct to neuroaxial anesthesia for lower limb procedures.[18]

Dosage and administration

Intravenous infusion of dexmedetomidine are commonly given at a dose of 0.2–1.4 micrograms/kg/hour.[3] An initial bolus of 0.5 to 1.0 ug/kg over about 15 min may be given.[2]

There are individual variability in the hemodynamic effects (especially on heart rate and blood pressure), as well as the sedative effects. For this reason, the dose must be adjusted to achieve the desired effect.[19]

Side effects

There is no absolute contraindication to the use of dexmedetomidine. It has a biphasic effect on blood pressure with lower readings at lower drug concentrations and higher readings at higher concentrations.[20] Rapid IV administration or bolus has been associated with hypertension due to peripheral α2-receptor stimulation. Bradycardia can be a limiting factor with infusions especially in higher doses.

Interactions

Dexmedetomidine may enhance the effects of other sedatives and anesthetics when co-administered. Similarly, drugs that lower blood pressure and heart rate, such as beta blockers, may also have enhanced effects when co-administered with dexmedetomidine.[21]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Dexmedetomidine is a highly selective α2-adrenergic agonist. It possesses an α2:α1 selectivity ratio of 1620:1, making it eight times more selective for the α2-receptor than clonidine.[22] Unlike opioids and other sedatives such as propofol, dexmedetomidine is able to achieve its effects without causing respiratory depression. Dexmedetomidine induces sedation by decreasing activity of noradrenergic neurons in the locus ceruleus in the brain stem, thereby increasing the downstream activity of inhibitory gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurons in the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus.[23] In contrast, other sedatives like propofol and benzodiazepines directly increase activity of gamma-aminobutyric acid neurons.[24] Through action on this endogenous sleep-promoting pathway the sedation produced by dexmedetomidine more closely mirrors natural sleep (specifically stage 2 non-rapid eye movement sleep), as demonstrated by EEG studies.[23][25] As such, dexmedetomidine provides less amnesia than benzodiazepines.[24] Dexmedetomidine also has analgesic effects at the spinal cord level and other supraspinal sites.[24] Thus, unlike other hypnotic agents like propofol, dexmedetomidine can be used as an adjunct medication to help decrease the opioid requirements of people in pain while still providing similar analgesia.

Pharmacokinetics

Intravenous dexmedetomidine exhibits linear pharmacokinetics with a rapid distribution half-life of approximately 6 minutes in healthy volunteers, and a longer and more variable distribution half-life in ICU patients.[26] The terminal elimination half-life of intravenous dexmedetomidine ranged 2.1-3.1 hours in healthy adults and 2.2-3.7 hours in ICU patients.[27] Plasma protein binding of dexmedetomidine is about 94% (mostly albumin).[28]

Dexmedetomidine is metabolized by the liver, largely by glucuronidation (34%) as well as by oxidation via CYP2A6 and other Cytochrome P450 enzymes.[27] As such, it should be used with caution in people with liver disease.[21]

The majority of metabolized dexmedetomidine is excreted in the urine (~95%).

History

Dexmedetomidine was approved in 1999 by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a short-term sedative and analgesic (<24 hours) for critically ill or injured people on mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit (ICU). The rationale for its short-term use was due to concerns over withdrawal side effects such as rebound high blood pressure. These effects have not been consistently observed in research studies, however.[29] In 2008 the FDA expanded its indication to include non-intubated people requiring sedation for surgical or non-surgical procedures, such as colonoscopy.

Society and culture

Cost

From an economic perspective, dexmedetomidine maybe associated with lower ICU costs in the United States, largely due to a shorter time to extubation.[30]

Veterinary use

Dexmedetomidine, under the trade name Dexdomitor (Orion Corporation), was approved in the European Union in for use in cats and dogs in 2002 for sedation and induction of general anesthesia.[31] The FDA approved dexmedetomidine for use in dogs in 2006 and cats in 2007.[32]

In 2015, the European Medicines Agency and the FDA approved an oromucosal gel form of dexmedetomidine marketed as Sileo (Zoetis) for use in dogs for relief of noise aversion.[33][34]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Dexmedetomidine Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 17 January 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- 1 2 Barash, Paul G.; Cullen, Bruce F.; Stoelting, Robert K.; Cahalan, Michael; Stock, M. Christine (1 January 2011). Clinical Anesthesia. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. PT3627. ISBN 978-1-4511-2297-8. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 BNF (80 ed.). BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. September 2020 – March 2021. p. 1416. ISBN 978-0-85711-369-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ↑ Cormack JR, Orme RM, Costello TG (2005). "The role of alpha2-agonists in neurosurgery". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 12 (4): 375–8. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2004.06.008. PMID 15925765. S2CID 79899746.

- ↑ "Dexdor". Archived from the original on 8 January 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ↑ "Dexdomitor for Animal Use". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ↑ Pasin, Laura; Greco, Teresa; Feltracco, Paolo; Vittorio, Annalisa; Neto, Caetano Nigro; Cabrini, Luca; Landoni, Giovanni; Finco, Gabriele; Zangrillo, Alberto (2013-01-01). "Dexmedetomidine as a sedative agent in critically ill patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". PLOS ONE. 8 (12): e82913. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...882913P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0082913. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3877008. PMID 24391726.

- 1 2 Chen, Ken; Lu, Zhijun; Xin, Yi Chun; Cai, Yong; Chen, Yi; Pan, Shu Ming (2015-01-01). "Alpha-2 agonists for long-term sedation during mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD010269. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010269.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6353054. PMID 25879090.

- 1 2 MacLaren, Robert; Preslaski, Candice R.; Mueller, Scott W.; Kiser, Tyree H.; Fish, Douglas N.; Lavelle, James C.; Malkoski, Stephen P. (2015-03-01). "A randomized, double-blind pilot study of dexmedetomidine versus midazolam for intensive care unit sedation: patient recall of their experiences and short-term psychological outcomes". Journal of Intensive Care Medicine. 30 (3): 167–175. doi:10.1177/0885066613510874. ISSN 1525-1489. PMID 24227448. S2CID 25036525.

- ↑ Li, Bo; Wang, Huixia; Wu, Hui; Gao, Chengjie (2015-04-01). "Neurocognitive dysfunction risk alleviation with the use of dexmedetomidine in perioperative conditions or as ICU sedation: a meta-analysis". Medicine. 94 (14): e597. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000000597. ISSN 1536-5964. PMC 4554047. PMID 25860207.

- ↑ Dere, Kamer; Sucullu, Ilker; Budak, Ersel Tan; Yeyen, Suleyman; Filiz, Ali Ilker; Ozkan, Sezai; Dagli, Guner (2010-07-01). "A comparison of dexmedetomidine versus midazolam for sedation, pain and hemodynamic control, during colonoscopy under conscious sedation". European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 27 (7): 648–652. doi:10.1097/EJA.0b013e3283347bfe. ISSN 1365-2346. PMID 20531094. S2CID 24778669.

- ↑ Paris A, Tonner PH (2005). "Dexmedetomidine in anaesthesia". Current Opinion in Anesthesiology. 18 (4): 412–8. doi:10.1097/01.aco.0000174958.05383.d5. PMID 16534267. S2CID 20014479.

- ↑ Giovannitti, Joseph A.; Thoms, Sean M.; Crawford, James J. (2015-01-01). "Alpha-2 Adrenergic Receptor Agonists: A Review of Current Clinical Applications". Anesthesia Progress. 62 (1): 31–38. doi:10.2344/0003-3006-62.1.31. ISSN 0003-3006. PMC 4389556. PMID 25849473.

- ↑ Ahmed, S. S.; Unland, T; Slaven, J. E.; Nitu, M. E.; Rigby, M. R. (2014). "Successful use of intravenous dexmedetomidine for magnetic resonance imaging sedation in autistic children". Southern Medical Journal. 107 (9): 559–64. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000160. PMID 25188619. S2CID 43652106.

- ↑ He, Xing-Ying; Cao, Jian-Ping; He, Qian; Shi, Xue-Yin (2014-01-19). "Dexmedetomidine for the management of awake fibreoptic intubation". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD009798. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009798.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 8095023. PMID 24442817.

- ↑ Menon DV, Wang Z, Fadel PJ, Arbique D, Leonard D, Li JL, Victor RG, Vongpatanasin W (2007). "Central sympatholysis as a novel countermeasure for cocaine-induced sympathetic activation and vasoconstriction in humans". J Am Coll Cardiol. 50 (7): 626–33. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.060. PMID 17692748.

- ↑ John R. Richards; Timothy E. Albertson; Robert W. Derlet; Richard A. Lange; Kent R. Olson; B. Zane Horowitz (February 2015). "Treatment of toxicity from amphetamines, related derivatives, and analogues: A systematic clinical review". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 150: 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.01.040. PMID 25724076. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-07-06.

- ↑ Mahendru, Vidhi; Tewari, Anurag; Katyal, Sunil; Grewal, Anju; Singh, M Rupinder; Katyal, Roohi (2013). "A comparison of intrathecal dexmedetomidine, clonidine, and fentanyl as adjuvants to hyperbaric bupivacaine for lower limb surgery: A double blind controlled study". Journal of Anaesthesiology Clinical Pharmacology. 29 (4): 496–502. doi:10.4103/0970-9185.119151. ISSN 0970-9185. PMC 3819844. PMID 24249987.

- ↑ "Dosing Guidelines for Precedex" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-15. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ↑ Ebert, T. J.; Hall, J. E.; Barney, J. A.; Uhrich, T. D.; Colinco, M. D. (2000-08-01). "The effects of increasing plasma concentrations of dexmedetomidine in humans". Anesthesiology. 93 (2): 382–394. doi:10.1097/00000542-200008000-00016. ISSN 0003-3022. PMID 10910487. S2CID 20795504.

- 1 2 Keating, Gillian M. (2015-07-01). "Dexmedetomidine: A Review of Its Use for Sedation in the Intensive Care Setting". Drugs. 75 (10): 1119–1130. doi:10.1007/s40265-015-0419-5. ISSN 0012-6667. PMID 26063213. S2CID 20447722.

- ↑ Scott-Warren, VL; Sebastian, J (2016). "Dexmedetomidine: its use in intensive care medicine and anaesthesia". BJA Education. 16 (7): 242–246. doi:10.1093/bjaed/mkv047. ISSN 2058-5349.

- 1 2 Nelson, Laura E.; Lu, Jun; Guo, Tianzhi; Saper, Clifford B.; Franks, Nicholas P.; Maze, Mervyn (2003-02-01). "The alpha2-adrenoceptor agonist dexmedetomidine converges on an endogenous sleep-promoting pathway to exert its sedative effects". Anesthesiology. 98 (2): 428–436. doi:10.1097/00000542-200302000-00024. ISSN 0003-3022. PMID 12552203. S2CID 5034487.

- 1 2 3 Panzer, Oliver; Moitra, Vivek; Sladen, Robert N. (2009-07-01). "Pharmacology of sedative-analgesic agents: dexmedetomidine, remifentanil, ketamine, volatile anesthetics, and the role of peripheral mu antagonists". Critical Care Clinics. 25 (3): 451–469, vii. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2009.04.004. ISSN 1557-8232. PMID 19576524.

- ↑ Huupponen, E.; Maksimow, A.; Lapinlampi, P.; Särkelä, M.; Saastamoinen, A.; Snapir, A.; Scheinin, H.; Scheinin, M.; Meriläinen, P. (2008-02-01). "Electroencephalogram spindle activity during dexmedetomidine sedation and physiological sleep". Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 52 (2): 289–294. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.2007.01537.x. ISSN 1399-6576. PMID 18005372. S2CID 34923432.

- ↑ Venn, R. M.; Karol, M. D.; Grounds, R. M. (May 2002). "Pharmacokinetics of dexmedetomidine infusions for sedation of postoperative patients requiring intensive caret". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 88 (5): 669–675. doi:10.1093/bja/88.5.669. ISSN 0007-0912. PMID 12067004.

- 1 2 Weerink, Maud A. S.; Struys, Michel M. R. F.; Hannivoort, Laura N.; Barends, Clemens R. M.; Absalom, Anthony R.; Colin, Pieter (2017). "Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Dexmedetomidine". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 56 (8): 893–913. doi:10.1007/s40262-017-0507-7. ISSN 0312-5963. PMC 5511603. PMID 28105598.

- ↑ "Precedex (Dexmedetomidine hydrochloride) Drug Information: Clinical Pharmacology - Prescribing Information at RxList". RxList. Archived from the original on 2015-11-17. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ↑ Shehabi, Yahya; Ruettimann, Urban; Adamson, Harriet; Innes, Richard; Ickeringill, Mathieu (2004-12-01). "Dexmedetomidine infusion for more than 24 hours in critically ill patients: sedative and cardiovascular effects". Intensive Care Medicine. 30 (12): 2188–2196. doi:10.1007/s00134-004-2417-z. ISSN 0342-4642. PMID 15338124. S2CID 26258023.

- ↑ Turunen, Heidi; Jakob, Stephan M.; Ruokonen, Esko; Kaukonen, Kirsi-Maija; Sarapohja, Toni; Apajasalo, Marjo; Takala, Jukka (2015-01-01). "Dexmedetomidine versus standard care sedation with propofol or midazolam in intensive care: an economic evaluation". Critical Care (London, England). 19: 67. doi:10.1186/s13054-015-0787-y. ISSN 1466-609X. PMC 4391080. PMID 25887576.

- ↑ Gozalo-Marcilla, M.; Gasthuys, F.; Luna, S. P. L.; Schauvliege, S. (April 2018). "Is there a place for dexmedetomidine in equine anaesthesia and analgesia? A systematic review (2005-2017)". Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 41 (2): 205–217. doi:10.1111/jvp.12474. PMID 29226340. S2CID 3691570. Archived from the original on 2021-02-03. Retrieved 2021-07-06.

- ↑ "Freedom of Information Summary | Supplemental New Animal Drug Application | NADA 141-267 | Dexdomitor". Food and Drug Administration. 16 August 2010. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2018-07-01.

- ↑ "Recent Animal Drug Approvals". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2 June 2016. Archived from the original on 12 July 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

For the treatment of noise aversion in dogs

- ↑ "Veterinary medicines: product update". Veterinary Record. 177 (5): 116–117. 31 July 2015. doi:10.1136/vr.h4051. PMID 26231872. S2CID 42312260.

External links

| External sites: |

|

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

- "Dexmedetomidine hydrochloride". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2021-06-21. Retrieved 2021-07-06.