Atomoxetine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Strattera, others |

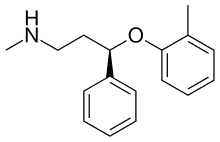

| Other names | (R)-N-Methyl-3-phenyl-3-(o-tolyloxy)propan-1-amine |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor[1] |

| Main uses | ADHD[1] |

| Side effects | Abdominal pain, loss of appetite, nausea, feeling tired, dizziness[1] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| Defined daily dose | 80 mg[3] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a603013 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 63 to 94%[4][5][6] |

| Protein binding | 98%[4][5][6] |

| Metabolism | Liver, via CYP2D6[4][5][6] |

| Elimination half-life | 4.5-19 hours[4][5][6][7][8] |

| Excretion | Kidney (80%) and faecal (17%)[4][5][6] |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H21NO |

| Molar mass | 255.361 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Atomoxetine, sold under the brand name Strattera, among others, is a medication used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).[1] It may be used alone or along with stimulants.[9][10] Use of atomoxetine is only recommended for those who are at least six years old.[1] It is taken by mouth.[1]

Common side effects of atomoxetine include abdominal pain, loss of appetite, nausea, feeling tired, and dizziness.[1] Serious side effects may include angioedema, liver problems, stroke, psychosis, heart problems, suicide, and aggression.[1][11] Its safety for use during pregnancy and breastfeeding is not yet certain.[12] Atomoxetine is a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and is believed to work by increasing norepinephrine and dopamine levels in the brain.[1][7]

Atomoxetine was approved for medical use in the United States in 2002.[1] A month's supply in the United Kingdom costs the NHS about £53 as of 2019.[11] In the United States, the wholesale cost of this amount is about US$77.[13] In 2017, it was the 199th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than two million prescriptions.[14][15]

Medical uses

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Atomoxetine is approved for use in children, adolescents, and adults.[16] However, its efficacy has not been studied in children under six years old.[5] Its primary advantage over the standard stimulant treatments for ADHD is that it has little known abuse potential.[5] While it has been shown to significantly reduce inattentive and hyperactive symptoms, the responses were lower than the response to stimulants. Additionally, 40% of participants who were treated with atomoxetine experienced residual ADHD symptoms.[17]

While its efficacy may be less than that of stimulant medications,[18] there is some evidence that it may be used in combination with stimulants.[9] Doctors may prescribe non-stimulants including atomoxetine when a person has bothersome side effects from stimulants; when a stimulant was not effective; or in combination with a stimulant to increase effectiveness.[19][20]

Unlike α2 adrenoceptor agonists such as guanfacine and clonidine, atomoxetine's use can be abruptly stopped without significant discontinuation effects being seen.[5]

The initial therapeutic effects of atomoxetine usually take 2–4 weeks to become apparent.[4] A further 2–4 weeks may be required for the full therapeutic effects to be seen.[21] The maximum recommended total daily dose in children and adolescents over 70 kg and adults is 100 mg.[16]

Other

Atomoxetine may be used in those with ADHD and bipolar disorder although such use has not been well studied.[22] Some benefit has also been seen in people with ADHD and autism.[23]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 80 mg by mouth.[3]

Contraindications

Contraindications include:[5]

- Hypersensitivity to atomoxetine or any of the inactive ingredients in the product

- Symptomatic cardiovascular disease including:

- -moderate to severe hypertension

- -atrial fibrillation

- -atrial flutter

- -ventricular tachycardia

- -ventricular fibrillation

- -ventricular flutter

- -advanced arteriosclerosis

- Severe cardiovascular disorders

- Pheochromocytoma

- Concomitant treatment with monoamine oxidase inhibitors

- Narrow angle glaucoma

- Poor metabolizers (due to the metabolism of atomoxetine by CYP2D6)

Side effects

Common side effects include abdominal pain, loss of appetite, nausea, feeling tired, and dizziness.[1] Serious side effects may include angioedema, liver problems, stroke, psychosis, heart problems, suicide, and aggression.[1][11] Safety in pregnancy and breastfeeding is not clear.[12]

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued a black box warning for suicidal behaviour/ideation.[6] Similar warnings have been issued in Australia.[5][24] Unlike stimulant medications, atomoxetine does not have abuse liability or the potential to cause withdrawal effects on abrupt discontinuation.[5]

Very common (>10% incidence)

- Nausea (26%)

- Xerostomia (Dry mouth) (20%)

- Appetite loss (16%)

- Insomnia (15%)

- Fatigue (10%)

- Headache

- Cough

- Vomiting (in children and adolescents)

Common (1–10% incidence)

- Constipation (8%)

- Dizziness (8%)

- Erectile dysfunction (8%)

- Somnolence (sleepiness) (8%)

- Abdominal pain (7%)

- Urinary hesitation (6%)

- Tachycardia (high heart rate) (5–10%)

- Hypertension (high blood pressure) (5–10%)

- Irritability (5%)

- Abnormal dreams (4%)

- Dyspepsia (4%)

- Ejaculation disorder (4%)

- Hyperhidrosis (abnormally increased sweating) (4%)

- Vomiting (4%)

- Hot flashes (3%)

- Paraesthesia (sensation of tingling, tickling, etc.) (3%)

- Menstrual disorder (3%)

- Weight loss (2%)

- Depression

- Sinus headache

- Dermatitis

- Mood swings

Uncommon (0.1–1% incidence)

- Suicide-related events

- Hostility

- Emotional lability

- Aggression

- Psychosis

- Syncope (fainting)

- Tremor

- Migraine

- Hypoaesthesia

- Seizure

- Palpitations

- Sinus tachycardia

- QT interval prolongation

- Increased blood bilirubin

- Allergic reactions

Rare (0.01–0.1% incidence)

- Raynaud's phenomenon

- Abnormal/increased liver function tests

- Jaundice

- Hepatitis

- Liver injury

- Acute liver failure

- Urinary retention

- Priapism[27]

- Male genital pain

Overdose

Atomoxetine is relatively non-toxic in overdose. Single-drug overdoses involving over 1500 mg of atomoxetine have not resulted in death.[5] The most common symptoms of overdose include:[5]

- Gastrointestinal symptoms

- Somnolence

- Dizziness

- Tremor

- Abnormal behaviour

- Hyperactivity

- Agitation

- Dry mouth

- Tachycardia

- Hypertension

- Mydriasis

Less common symptoms:[5]

- Seizures

- QTc interval prolongation

The recommended treatment for atomoxetine overdose includes use of activated charcoal to prevent further absorption of the drug.[5]

Interactions

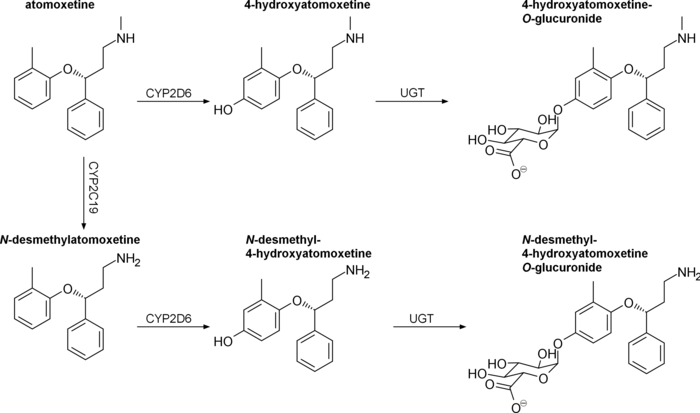

Atomoxetine is a substrate for CYP2D6. Concurrent treatment with a CYP2D6 inhibitor such as bupropion, fluoxetine, or paroxetine has been shown to increase plasma atomoxetine by 100% or more, as well as increase N-desmethylatomoxetine levels and decrease plasma 4-hydroxyatomoxetine levels by a similar degree.[28][29][30]

Atomoxetine has been found to directly inhibit hERG potassium currents with an IC50 of 6.3 μM, which has the potential to cause arrhythmia.[29][31] QT prolongation has been reported with atomoxetine at therapeutic doses and in overdose; it is suggested that atomoxetine not be used with other medications that may prolong the QT interval, concomitantly with CYP2D6 inhibitors, and caution to be used in poor metabolizers.[29]

Other notable drug interactions include:[5]

- Antihypertensive agents, due to atomoxetine acting as an indirect sympathomimetic

- Indirect-acting sympathomimetics, such as pseudoephedrine, norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, or MAOIs

- Direct-acting sympathomimetics, such as phenylephrine or other α1 adrenoceptor agonists, including pressors such as dobutamine or isoprenaline and β2 adrenoceptor agonists

- Highly plasma protein-bound drugs: atomoxetine has the potential to displace these drugs from plasma proteins which may potentiate their adverse or toxic effects. In vitro, atomoxetine does not affect the plasma protein binding of aspirin, desipramine, diazepam, paroxetine, phenytoin, or warfarin[7][32]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | ATX | 4-OH-ATX | N-DM-ATX | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SERT | 77 | 43 | ND | |

| NET | 5 | 3 | 92 | |

| DAT | 1,451 | ND | ND | |

| 5-HT1A | >1,000 | ND | ND | |

| 5-HT1B | >1,000 | ND | ND | |

| 5-HT1D | >1,000 | ND | ND | |

| 5-HT2 | 2,000 | 1,000 | 1,700 | |

| 5-HT6 | >1,000 | ND | ND | |

| 5-HT7 | >1,000 | ND | ND | |

| α1 | 11,400 | 20,000 | 19,600 | |

| α2A | 29,800 | >30,000 | >10,000 | |

| β1 | 18,000 | 56,100 | 32,100 | |

| M1 | >100,000 | >100,000 | >100,000 | |

| M2 | >100,000 | >100,000 | >100,000 | |

| D1 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | |

| D2 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | |

| H1 | 12,100 | >100,000 | >100,000 | |

| MOR | ND | 422 | ND | |

| DOR | ND | 300 | ND | |

| KOR | ND | 95 | ND | |

| σ1 | >1,000 | ND | ND | |

| GABAA | 200 | >30,000 | >10,000 | |

| NMDA | 3,470a | ND | ND | |

| Kir3.1/3.2 | 10,900b | ND | ND | |

| Kir3.2 | 12,400b | ND | ND | |

| Kir3.1/3.4 | 6,500b | ND | ND | |

| hERG | 6,300 | 20,000 | 5,710 | |

| Values are Ki (nM). The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. All values are for human receptors unless otherwise specified. arat cortex. bXenopus oocytes. Additional sources:[35][36][35][7][32] | ||||

Atomoxetine inhibits the presynaptic norepinephrine transporter (NET), preventing the reuptake of norepinephrine throughout the brain along with inhibiting the reuptake of dopamine in specific brain regions such as the prefrontal cortex, where dopamine transporter (DAT) expression is minimal.[7] In rats, atomoxetine increased prefrontal cortex catecholamine concentrations without altering dopamine levels in the striatum or nucleus accumbens; in contrast, methylphenidate, a dopamine reuptake inhibitor, was found to increase prefrontal, striatal, and accumbal dopamine levels to the same degree.[35] In mice, atomoxetine was also found to increase prefrontal catecholamine levels without affecting striatal or accumbal levels.[37]

Atomoxetine's status as a serotonin transporter (SERT) inhibitor at clinical doses in humans is uncertain. A PET imaging study on rhesus monkeys found that atomoxetine occupied >90% and >85% of neural NET and SERT, respectively.[38] However, both mouse and rat microdialysis studies have failed to find an increase in extracellular serotonin in the prefrontal cortex following acute or chronic atomoxetine treatment.[35][37] Supporting atomoxetine's selectivity, a human study found no effects on platelet serotonin uptake (a marker of SERT inhibition) and inhibition of the pressor effects of tyramine (a marker of NET inhibition).[39]

Atomoxetine has been found to act as an NMDA receptor antagonist in rat cortical neurons at therapeutic concentrations.[40][41] It causes a use-dependent open-channel block and its binding site overlaps with the Mg2+ binding site.[40][41] Atomoxetine's ability to increase prefrontal cortex firing rate in anesthetized rats could not be blocked by D1 or α2-adrenergic receptor antagonists, but could be potentiated by NMDA or an α1-adrenergic receptor antagonist, suggesting a glutaminergic mechanism.[42] In Sprague Dawley rats, atomoxetine reduces NR2B protein content without altering transcript levels.[43] Aberrant glutamate and NMDA receptor function have been implicated in the etiology of ADHD.[44][45]

Atomoxetine also reversibly inhibits GIRK currents in Xenopus oocytes in a concentration-dependent, voltage-independent, and time-independent manner.[46] Kir3.1/3.2 ion channels are opened downstream of M2, α2, D2, and A1 stimulation, as well as other Gi-coupled receptors.[46] Therapeutic concentrations of atomoxetine are within range of interacting with GIRKs, especially in CYP2D6 poor metabolizers.[46] It is not known whether this contributes to the therapeutic effects of atomoxetine in ADHD.

4-Hydroxyatomoxetine, the major active metabolite of atomoxetine in CYP2D6 extensive metabolizers, has been found to have sub-micromolar affinity for opioid receptors, acting as an antagonist at μ-opioid receptors and a partial agonist at κ-opioid receptors.[36] It is not known whether this contributes to the therapeutic effects of atomoxetine in ADHD.

Pharmacokinetics

Orally administered atomoxetine is rapidly and completely absorbed.[7] First-pass metabolism by the liver is dependent on CYP2D6 activity, resulting in an absolute bioavailability of 63% for extensive metabolizers and 94% for poor metabolizers.[7] Maximum plasma concentration is reached in 1–2 hours.[7] If taken with food, the maximum plasma concentration decreases by 10-40% and delays the tmax by 1 hour.[7] Drugs affecting gastric pH have no effect on oral bioavailability.[16]

Atomoxetine has a volume of distribution of 0.85 L/kg, with limited partitioning into red blood cells.[7] It is highly bound to plasma proteins (98.7%), mainly albumin, along with α1-acid glycoprotein (77%) and IgG (15%).[7][32] Its metabolite N-desmethylatomoxetine is 99.1% bound to plasma proteins, while 4-hydroxyatomoxetine is only 66.6% bound.[7]

The half-life of atomoxetine varies widely between individuals, with an average range of 4.5 to 19 hours.[7][8] As atomoxetine is metabolized by CYP2D6, exposure may be increased 10-fold in CYP2D6 poor metabolizers.[8]

Atomoxetine, N-desmethylatomoxetine, and 4-hydroxyatomoxetine produce minimal to no inhbition of CYP1A2 and CYP2C9, but inhibit CYP2D6 in human liver microsomes at concentrations between 3.6-17 μmol/L. Plasma concentrations of 4-hydroxyatomoxetine and N-desmethylatomoxetine at steady state are 1.0% and 5% that of atomoxetine in CYP2D6 extensive metabolizers, and are 5% and 45% that of atomoxetine in CYP2D6 poor metabolizers.[16]

Atomoxetine is excreted unchanged in urine at <3% in both extensive and poor CYP2D6 metabolizers, with >96% and 80% of a total dose being excreted in urine, respectively.[7] The fractions excreted in urine as 4-hydroxyatomoxetine and its glucuronide account for 86% of a given dose in extensive metabolizers, but only 40% in poor metabolizers.[7] CYP2D6 poor metabolizers excrete greater amounts of minor metabolites, namely N-desmethylatomoxetine and 2-hydroxymethylatomoxetine and their conjugates.[7]

Pharmacogenomics

Chinese adults homozygous for the hypoactive CYP2D6*10 allele have been found to exhibit two-fold higher AUCs and 1.5-fold higher maximum plasma concentrations compared to extensive metabolizers.[7]

Japanese men homozygous for CYP2D6*10 have similarly been found to experience two-fold higher AUCs compared to extensive metabolizers.[7]

Chemistry

Atomoxetine, or (−)-methyl[(3R)-3-(2-methylphenoxy)-3-phenylpropyl]amine, is a white, granular powder that is highly soluble in water.

Strattera 60-mg capsule back

Strattera 60-mg capsule back Strattera 60-mg capsule front with Lilly logo

Strattera 60-mg capsule front with Lilly logo

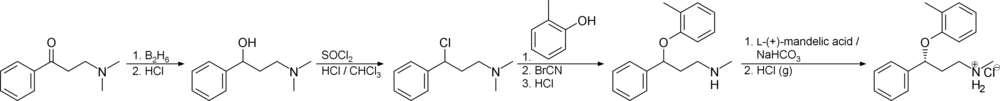

Synthesis

Detection in biological fluids

Atomoxetine may be quantitated in plasma, serum or whole blood in order to distinguish extensive versus poor metabolizers in those receiving the drug therapeutically, to confirm the diagnosis in potential poisoning victims or to assist in the forensic investigation in a case of fatal overdosage.[49]

History

Atomoxetine is manufactured, marketed, and sold in the United States as the hydrochloride salt (atomoxetine HCl) under the brand name Strattera by Eli Lilly and Company, the original patent-filing company and current U.S. patent owner. Atomoxetine was initially intended to be developed as an antidepressant, but it was found to be insufficiently efficacious for treating depression. It was, however, found to be effective for ADHD and was approved by the FDA in 2002, for the treatment of ADHD. Its patent expired in May 2017.[50] On 12 August 2010, Lilly lost a lawsuit that challenged its patent on Strattera, increasing the likelihood of an earlier entry of a generic into the US market.[51] On 1 September 2010, Sun Pharmaceuticals announced it would begin manufacturing a generic in the United States.[52] In a 29 July 2011 conference call, however, Sun Pharmaceutical's Chairman stated "Lilly won that litigation on appeal so I think [generic Strattera]'s deferred."[53]

In 2017 the FDA approved the generic production of atomoxetine by four pharmaceutical companies.[54]

Society and culture

Cost

In the United States, the wholesale cost of this amount is about US$77.[13] In 2017, it was the 199th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than two million prescriptions.[14][15]

.svg.png.webp) Costs (USA)

Costs (USA).svg.png.webp) Prescriptions (USA)

Prescriptions (USA)

Brand names

In India, atomoxetine is sold under brand names including Axetra, Axepta, Attera, Tomoxetin, and Attentin. In Australia, Portugal and Romania, atomoxetine is sold under the brand name Strattera. In Iran, atomoxetine is sold under brand names including Stramox. In 2017, a generic version was approved in the United States.[54]

Research

There has been some suggestion that atomoxetine might be a helpful adjunct in people with major depression, particularly in cases with concomitant ADHD.[55]

Atomoxetine may improve working memory and attention when used at certain doses.[55]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Atomoxetine Hydrochloride Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- 1 2 "Atomoxetine (Strattera) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 22 August 2019. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "atomoxetine (Rx) – Strattera". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 "Strattera (atomoxetine hydrochloride)". TGA eBusiness Services. Eli Lilly Australia Pty. Limited. 21 August 2013. Archived from the original on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "ATOMOXETINE HYDROCHLORIDE capsule [Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc.]". DailyMed. Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc. October 2011. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Sauer JM, Ring BJ, Witcher JW (2005). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of atomoxetine". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 44 (6): 571–90. doi:10.2165/00003088-200544060-00002. PMID 15910008.

- 1 2 3 Brown JT, Bishop JR (2015). "Atomoxetine pharmacogenetics: associations with pharmacokinetics, treatment response and tolerability". Pharmacogenomics. 16 (13): 1513–20. doi:10.2217/PGS.15.93. PMID 26314574.

- 1 2 Treuer T, Gau SS, Méndez L, Montgomery W, Monk JA, Altin M, Wu S, Lin CC, Dueñas HJ (April 2013). "A systematic review of combination therapy with stimulants and atomoxetine for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, including patient characteristics, treatment strategies, effectiveness, and tolerability". Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 23 (3): 179–93. doi:10.1089/cap.2012.0093. PMC 3696926. PMID 23560600.

- ↑ "Parent's Medication Guide: ADHD". American Psychiatric Association (Guidelines (Tertiary source)). American Psychiatric Association & American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP). June 2013. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

Though not FDA-approved for combined treatment, atomoxetine (Strattera) is sometimes used in conjunction with stimulants as an off-label combination therapy.

- 1 2 3 British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. pp. 344–345. ISBN 9780857113382.

- 1 2 "Atomoxetine Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- 1 2 "NADAC as of 2019-02-27". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- 1 2 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- 1 2 "Atomoxetine Hydrochloride - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 "Strattera (atomoxetine) Capsules for Oral Use". DailyMed.gov. Eli Lilly and Company. 29 January 2020. Archived from the original on 7 June 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ↑ Ghuman JK, Hutchison SL (November 2014). "Atomoxetine is a second-line medication treatment option for ADHD". Evidence-Based Mental Health. 17 (4): 108. doi:10.1136/eb-2014-101805. PMID 25165169. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ↑ Kooij, JJS (2013). Adult ADHD Diagnostic Assessment and Treatment. Springer London. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-4138-9. ISBN 978-1-4471-4137-2.

- ↑ "NIMH » Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder". NIMH » Home.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Institute of Mental Health.. Archived from the original on 25 December 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Institute of Mental Health.. Archived from the original on 25 December 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2018.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ "NIMH » Mental Health Medications". NIMH » Home. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ↑ Taylor D, Paton C, Shitij K (2012). The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-470-97948-8.

- ↑ Perugi G, Vannucchi G (2015). "The use of stimulants and atomoxetine in adults with comorbid ADHD and bipolar disorder". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 16 (14): 2193–204. doi:10.1517/14656566.2015.1079620. PMID 26364896.

- ↑ Matthew Siegel, MD., Craig Erickson, MD., MS, Jean A. Frazier, MD., Toni Ferguson, Autism Society of America., Eric Goepfert, MD., Gagan Joshi, MD., Quentin Humberd, MD., Bryan H. King, MD., Amy Lutz, EASI Foundation: Ending Aggression and Self-Injury in the Developmentally Disabled., Louis Kraus, MD., Alice Mao, MD., Adelaide Robb, MD., Jeremy Veenstra-VanderWeele, MD, PhD., Paul Wang, MD, Autism SpeaksCarmen J. Head, MPH, CHES, Director, Research, Development, & WorkforceEve, Bender, Scientific Editor. (2016). Autism_Spectrum_Disorder_Parents_Medication_Guide (PDF). Washington, DC: American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. p. 13. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 April 2017.

Atomoxetine (Strattera) has also been researched in controlled studies for treatment of ADHD in children with autism, and showed some improvements, particularly for hyperactivity and impulsivity

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Atomoxetine and suicidality in children and adolescents". Australian Prescriber. Vol. 36, no. 5. October 2013. p. 166. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ↑ "Strattera 10mg, 18mg, 25mg, 40mg, 60mg, 80mg or 100mg hard capsules". electronic Medicines Compendium. 28 May 2013. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ↑ "Strattera Product Insert". Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ↑ "Strattera Medication Guide" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Eli Lilly and Company. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 December 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ↑ Todor I, Popa A, Neag M, Muntean D, Bocsan C, Buzoianu A, Vlase L, Gheldiu AM, Briciu C (April–June 2016). "Evaluation of a Potential Metabolism-Mediated Drug-Drug Interaction Between Atomoxetine and Bupropion in Healthy Volunteers". Journal of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences. 19 (2): 198–207. doi:10.18433/j3h03r. PMID 27518170.

- 1 2 3 Kasi PM, Mounzer R, Gleeson GH (2011). "Cardiovascular side effects of atomoxetine and its interactions with inhibitors of the cytochrome p450 system". Case Reports in Medicine. 2011: 952584. doi:10.1155/2011/952584. PMC 3135225. PMID 21765848.

- ↑ Belle DJ, Ernest CS, Sauer JM, Smith BP, Thomasson HR, Witcher JW (November 2002). "Effect of potent CYP2D6 inhibition by paroxetine on atomoxetine pharmacokinetics". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 42 (11): 1219–27. doi:10.1177/009127002762491307. PMID 12412820.

- ↑ Scherer D, Hassel D, Bloehs R, Zitron E, von Löwenstern K, Seyler C, Thomas D, Konrad F, Bürgers HF, Seemann G, Rottbauer W, Katus HA, Karle CA, Scholz EP (January 2009). "Selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor atomoxetine directly blocks hERG currents". British Journal of Pharmacology. 156 (2): 226–36. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00018.x. PMC 2697834. PMID 19154426.

- 1 2 3 "21-411 Strattera Clinical Pharmacology Biopharmaceutics Review Part 2" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ↑ Roth BL, Driscol J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ↑ Upadhyaya, Himanshu P.; Desaiah, Durisala; Schuh, Kory J.; Bymaster, Frank P.; Kallman, Mary J.; Clarke, David O.; Durell, Todd M.; Trzepacz, Paula T.; Calligaro, David O.; Nisenbaum, Eric S.; Emmerson, Paul J.; Schuh, Leslie M.; Bickel, Warren K.; Allen, Albert J. (9 February 2013). "A review of the abuse potential assessment of atomoxetine: a nonstimulant medication for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Psychopharmacology. Springer Nature. 226 (2): 189–200. doi:10.1007/s00213-013-2986-z. ISSN 0033-3158. PMC 3579642. PMID 23397050.

- 1 2 3 4 Bymaster FP, Katner JS, Nelson DL, Hemrick-Luecke SK, Threlkeld PG, Heiligenstein JH, Morin SM, Gehlert DR, Perry KW (November 2002). "Atomoxetine increases extracellular levels of norepinephrine and dopamine in prefrontal cortex of rat: a potential mechanism for efficacy in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Neuropsychopharmacology. 27 (5): 699–711. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00346-9. PMID 12431845.

- 1 2 Creighton CJ, Ramabadran K, Ciccone PE, Liu J, Orsini MJ, Reitz AB (August 2004). "Synthesis and biological evaluation of the major metabolite of atomoxetine: elucidation of a partial kappa-opioid agonist effect". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 14 (15): 4083–5. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.05.018. PMID 15225731.

- 1 2 Koda K, Ago Y, Cong Y, Kita Y, Takuma K, Matsuda T (July 2010). "Effects of acute and chronic administration of atomoxetine and methylphenidate on extracellular levels of noradrenaline, dopamine and serotonin in the prefrontal cortex and striatum of mice". Journal of Neurochemistry. 114 (1): 259–70. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06750.x. PMID 20403082.

- ↑ Ding YS, Naganawa M, Gallezot JD, Nabulsi N, Lin SF, Ropchan J, Weinzimmer D, McCarthy TJ, Carson RE, Huang Y, Laruelle M (February 2014). "Clinical doses of atomoxetine significantly occupy both norepinephrine and serotonin transports: Implications on treatment of depression and ADHD". NeuroImage. 86: 164–71. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.08.001. PMID 23933039.

The noradrenergic action also exerts an important clinical effect in different antidepressant classes such as desipramine and nortriptyline (tricyclics, prevalent noradrenergic effect), reboxetine and atomoxetine (relatively pure noradrenergic reuptake inhibitor (NRIs)), and dual action antidepressants such as the serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), the noradrenergic and dopaminergic reuptake inhibitor (NDRI) bupropion, and other compounds (e.g., mianserin, mirtazapine), which enhance the noradrenergic transmission

- ↑ Zerbe RL, Rowe H, Enas GG, Wong D, Farid N, Lemberger L (January 1985). "Clinical pharmacology of tomoxetine, a potential antidepressant". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 232 (1): 139–43. PMID 3965689.

- 1 2 Ludolph AG, Udvardi PT, Schaz U, Henes C, Adolph O, Weigt HU, Fegert JM, Boeckers TM, Föhr KJ (May 2010). "Atomoxetine acts as an NMDA receptor blocker in clinically relevant concentrations". British Journal of Pharmacology. 160 (2): 283–91. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00707.x. PMC 2874851. PMID 20423340.

- 1 2 Barygin OI, Nagaeva EI, Tikhonov DB, Belinskaya DA, Vanchakova NP, Shestakova NN (April 2017). "Inhibition of the NMDA and AMPA receptor channels by antidepressants and antipsychotics". Brain Research. 1660: 58–66. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2017.01.028. PMID 28167075.

- ↑ Di Miceli M, Gronier B (June 2015). "Psychostimulants and atomoxetine alter the electrophysiological activity of prefrontal cortex neurons, interaction with catecholamine and glutamate NMDA receptors". Psychopharmacology. 232 (12): 2191–205. doi:10.1007/s00213-014-3849-y. PMID 25572531.

- ↑ Udvardi PT, Föhr KJ, Henes C, Liebau S, Dreyhaupt J, Boeckers TM, Ludolph AG (2013). "Atomoxetine affects transcription/translation of the NMDA receptor and the norepinephrine transporter in the rat brain--an in vivo study". Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 7: 1433–46. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S50448. PMC 3857115. PMID 24348020.

- ↑ Maltezos S, Horder J, Coghlan S, Skirrow C, O'Gorman R, Lavender TJ, Mendez MA, Mehta M, Daly E, Xenitidis K, Paliokosta E, Spain D, Pitts M, Asherson P, Lythgoe DJ, Barker GJ, Murphy DG (March 2014). "Glutamate/glutamine and neuronal integrity in adults with ADHD: a proton MRS study". Translational Psychiatry. 4 (3): e373. doi:10.1038/tp.2014.11. PMC 3966039. PMID 24643164.

- ↑ Chang JP, Lane HY, Tsai GE (2014). "Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) dysregulation". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 20 (32): 5180–5. doi:10.2174/1381612819666140110115227. PMID 24410567.

- 1 2 3 Kobayashi T, Washiyama K, Ikeda K (June 2010). "Inhibition of G-protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channels by the selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors atomoxetine and reboxetine". Neuropsychopharmacology. 35 (7): 1560–9. doi:10.1038/npp.2010.27. PMC 3055469. PMID 20393461.

- ↑ A US patent 4018895 A, Bryan B. Molloy & Klaus K. Schmiegel, "Aryloxyphenylpropylamines in treating depression", published 1977-04-19, assigned to Eli Lilly And Company

- ↑ B1 US patent EP0052492 B1, Bennie Joe Foster & Edward Ralph Lavagnino, "3-aryloxy-3-phenylpropylamines", published 1984-02-29, assigned to Eli Lilly And Company

- ↑ Baselt, Randall C. (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 118–20. ISBN 978-0-931890-08-6.

- ↑ "Patent and Exclusivity Search Results". Electronic Orange Book. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- ↑ "Drugmaker Eli Lilly loses patent case over ADHD drug, lowers revenue outlook". Chicago Tribune.

- ↑ "Sun Pharma receives USFDA approval for generic Strattera capsules". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 7 April 2011.

- ↑ "Sun Pharma Q1 2011-12 Earnings Call Transcript 10.00 am, July 29, 2011" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2011.

- 1 2 "FDA approves first generic Strattera for the treatment of ADHD". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 30 May 2017. Archived from the original on 4 June 2017. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- 1 2 Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE, Holtzman DM (2015). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 9780071827706.

Further reading

- Dean L (2015). "Atomoxetine Therapy and CYP2D6 Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28520366. Bookshelf ID: NBK315951. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

External links

| External sites: |

|

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- "Strattera (Atomoxetine) - Published Studies". Druglib. Archived from the original on 14 March 2008. Retrieved 1 January 2008.