Methysergide

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Deseril, Sansert |

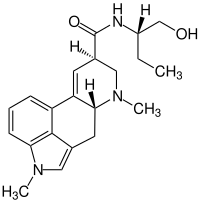

| Other names | UML-491; 1-Methylmethylergonovine; N-[(2S)-1-Hydroxybutan-2-yl]-1,6-dimethyl-9,10-didehydroergoline-8α-carboxamide; N-(1-(Hydroxymethyl)propyl)-1-methyl-D-lysergamide |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| MedlinePlus | a603022 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.041 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H27N3O2 |

| Molar mass | 353.466 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Methysergide, sold under the brand names Deseril and Sansert, is a monoaminergic medication of the ergoline and lysergamide groups which is used in the prophylaxis and treatment of migraine and cluster headaches.[1] It has been withdrawn from the market in the United States and Canada due to adverse effects.[2] It is taken by mouth.[2]

Methysergide is no longer recommended as a first line treatment protocol by international headache societies, hospitals, and neurologists in private practice, for migraines or cluster headaches as side effects were first reported with long-term use in the late 1960s, and ergot-based treatments fell out of favor for the treatment of migraines with the introduction of triptans in the 1980s.

Medical uses

Methysergide is used exclusively to treat episodic and chronic migraine and for episodic and chronic cluster headaches.[3] Methysergide is one of the most effective[4] medications for the prevention of migraine, but is not intended for the treatment of an acute attack, it is to be taken daily as a preventative medication.

Migraine and cluster headaches

Methysergide has been known as an effective treatment for migraine and cluster headache for over 50 years. A 2016 investigation by the European Medicines Agency due to long-held questions about safety concerns was performed. To assess the need for continuing availability of methysergide, the International Headache Society performed an electronic survey among their professional members.

The survey revealed that 71.3% of all respondents had ever prescribed methysergide and 79.8% would prescribe it if it were to become available. Respondents used it more in cluster headache than migraine, and reserved it for use in refractory patients.

The European Medicines Agency concluded "that the vast majority of headache experts in this survey regarded methysergide a unique treatment option for specific populations for which there are no alternatives, with an urgent need to continue its availability."

This position was supported by the International Headache Society.[5]

Updated guidelines published by Britain's National Health Service Migraine Trust in 2014 recommended "Methysergide medicines are now only to be used for preventing severe intractable migraine and cluster headache when standard medicines have failed".[6]

Other uses

Methysergide is also used in carcinoid syndrome to treat severe diarrhea.[3] It may also be used in the treatment of serotonin syndrome.[7]

Side effects

It has a known side effect, retroperitoneal fibrosis/retropulmonary fibrosis,[8] which is severe, although uncommon. This side effect has been estimated to occur in 1/5000 patients.[9] In addition, there is an increased risk of left-sided cardiac valve dysfunction.[4]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Methysergide interacts with the serotonin 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, 5-HT1E, 5-HT1F, 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, 5-HT2C, 5-HT5A, 5-HT6, and 5-HT7 receptors and the α2A-, α2B-, and α2C-adrenergic receptors.[10] It does not have significant affinity for human 5-HT3, dopamine, α1-adrenergic, β-adrenergic, acetylcholine, GABA, glutamate, cannabinoid, or histamine receptors, nor for the monoamine transporters.[10] Methysergide is an agonist of 5-HT1 receptors, including a partial agonist at the 5-HT1A receptor, and is an antagonist at the 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, 5-HT2C, and 5-HT7 receptors.[2][11][12][13][14][15] Methysergide is metabolized into methylergometrine in humans, which in contrast to methysergide is a partial agonist of the 5-HT2A and 5-HT2B receptors[16][15] and also interacts with various other targets.[17]

Methysergide antagonizes the effects of serotonin in blood vessels and gastrointestinal smooth muscle, but has few of the properties of other ergot alkaloids.[18] It is thought that metabolism of methysergide into methylergonovine is responsible for the antimigraine effects of methysergide.[19] Methylergonovine appears to be 10 times more potent than methysergide as an agonist of the 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors and has higher intrinsic eficacy in activating these receptors.[20] Methysergide produces psychedelic effects at high doses (3.5–7.5 mg).[21] Metabolism of methysergide into methylergometrine is considered to be responsible for the psychedelic effects of methysergide.[17] The psychedelic effects can specifically be attributed to activation of the 5-HT2A receptor.[22] The medication can activate the 5-HT2B receptor due to metabolism into methylergometrine and for this reason has been associated with cardiac valvulopathy.[23][24] It is thought that the serotonin receptor antagonism of methysergide is not able to overcome the serotonin receptor agonism of methylergonovine due to the much higher levels of methylergonovine during methysergide therapy.[24]

| Site | Affinity (Ki [nM]) | Efficacy (Emax [%]) | Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | 14–25 | 89% | Full or partial agonist |

| 5-HT1B | 2.5–162 | ? | Full agonist |

| 5-HT1D | 3.6–93 | 50 | Partial agonist |

| 5-HT1E | 59–324 | ? | Full agonist |

| 5-HT1F | 34 | ? | Full agonist |

| 5-HT2A | 1.6–104 | 0 | Antagonist or agonist |

| 5-HT2B | 0.1–150 | 0–20 | Silent antagonist or weak partial agonist |

| 5-HT2C | 0.95–4.5 | 0 | Silent antagonist |

| 5-HT3 | >10,000 | – | – |

| 5-HT5A | >10,000 | – | Antagonist |

| 5-HT5B | 41–1,000 | ? | ? |

| 5-HT6 | 30–372 | ? | ? |

| 5-HT7 | 30–83 | ? | Antagonist |

| α1A | >10,000 | – | – |

| α1B | >10,000 | – | – |

| α1D | ? | ? | ? |

| α2A | 170–>1,000 | ? | ? |

| α2B | 106 | ? | ? |

| α2C | 88 | ? | ? |

| β1 | >10,000 | – | – |

| β2 | >10,000 | – | – |

| D1 | 290 | ? | ? |

| D2 | 200–>10,000 | ? | ? |

| D3 | >10,000 | – | – |

| D4 | >10,000 | – | – |

| D5 | >10,000 | – | – |

| H1 | 3,000–>10,000 | ? | ? |

| H2 | >10,000 | – | – |

| M1 | 5,459 | ? | ? |

| M2 | 6,126 | ? | ? |

| M3 | 4,632 | ? | ? |

| M4 | >10,000 | – | – |

| M5 | >10,000 | – | – |

| Notes: All sites are human except 5-HT5B (mouse/rat—no human counterpart) and D3 (rat).[10] Negligible affinity (>10,000 nM) for various other receptors (GABA, glutamate, nicotinic acetylcholine, prostanoid) and for the monoamine transporters (SERT, NET, DAT).[10] Methysergide's major active metabolite, methylergometrine, also contributes to its activity, most notably 5-HT2A and 5-HT2B receptor partial agonism.[16][23][2][26] | |||

Pharmacokinetics

The oral bioavailability of methysergide is 13% due to high first-pass metabolism into methylergometrine.[19] Methysergide produces methylergometrine as a major active metabolite.[19][24][20] Levels of methylergometrine are about 10-fold higher than those of methysergide during methysergide therapy.[19][24][20] As such, methysergide may be considered a prodrug of methylergonovine.[20] The elimination half-life of methylergonovine is almost four times as long as that of methysergide.[20]

Chemistry

Methysergide, also known as N-[(2S)-1-hydroxybutan-2-yl]-1,6-dimethyl-9,10-didehydroergoline-8α-carboxamide or N-(1-(hydroxymethyl)propyl)-1-methyl-D-lysergamide, is a derivative of the ergolines and lysergamides and is structurally related to other members of these families, for instance lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD).

History

Harold Wolff's theory of vasodilation in migraine is well-known. Less known is his search for a perivascular factor that would damage local tissues and increase pain sensitivity during migraine attacks. Serotonin was found to be among the candidate agents to be included.

In the same period, serotonin was isolated (1948) and, because of its actions, an anti-serotonin drug was needed.

Methysergide was synthesized from lysergic acid by adding a methyl group and a butanolamid group. This resulted in a compound with selectivity and high potency as a serotonin (5-HT) inhibitor. Based on the possible involvement of serotonin in migraine attacks, it was introduced in 1959 by Sicuteri as a preventive drug for migraine. The clinical effect was often excellent, but 5 years later it was found to cause retroperitoneal fibrosis after chronic intake.

Consequently, the use of the drug in migraine declined considerably, but it was still used as a 5-HT antagonist in experimental studies. In 1974 Saxena showed that methysergide had a selective vasoconstrictor effect in the carotid bed and in 1984 he found an atypical receptor. This finding provided an incentive for the development of sumatriptan.[28]

Novartis withdrew it from the U.S. market after taking over Sandoz, but currently lists it as a discontinued product.[29]

Production and availability

US production of Methysergide, (Sansert), was discontinued on the manufacturer's own behalf in 2002. Sansert had previously been produced by Sandoz, which merged with Ciba-Geigy in 1996, and led to the creation of Novartis. In 2003 Novartis united its global generics businesses under a single global brand, with the Sandoz name and product line reviewed and reestablished.

Society and culture

Controversy

Methysergide has been an effective treatment for migraine and cluster headache for over 50 years but has systematically been suppressed from the migraine and cluster headache marketplace for over 15 years due to unqualified risk benefit/ratio safety concerns.[30]

Many cite the potential side effects of retroperitoneal/retropulmonary fibrosis as the prime reason methysergide is no longer frequently prescribed, but retroperitoneal fibrosis, and retropulmonary fibrosis, were documented as side effects as early as 1966,[31] and 1967,[32] respectively.

References

- ↑ Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 677–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ramírez Rosas MB, Labruijere S, Villalón CM, Maassen Vandenbrink A (August 2013). "Activation of 5-hydroxytryptamine1B/1D/1F receptors as a mechanism of action of antimigraine drugs". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 14 (12): 1599–610. doi:10.1517/14656566.2013.806487. PMID 23815106. S2CID 22721405.

- 1 2 "tranquilene page – Tranquility Labs".

- 1 2 Joseph T, Tam SK, Kamat BR, Mangion JR (2003). "Successful repair of aortic and mitral incompetence induced by methylsergide maleate: confirmation by intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography". Echocardiography. 20 (3): 283–7. doi:10.1046/j.1540-8175.2003.03027.x. PMID 12848667. S2CID 22513342.

- ↑ MacGregor, E. Anne; Evers, Stefan; International Headache Society (2016-07-21). "The role of methysergide in migraine and cluster headache treatment worldwide - A survey in members of the International Headache Society". Cephalalgia: An International Journal of Headache. 37 (11): 1106–1108. doi:10.1177/0333102416660551. ISSN 1468-2982. PMID 27449673. S2CID 206521928.

- ↑ "Methysergide - The Migraine Trust". The Migraine Trust. Retrieved 2017-09-06.

- ↑ Sporer, KA (1995). "The Serotonin Syndrome Implicated Drugs, Pathophysiology and Management". Drug Safety. 13 (2): 94–104. doi:10.2165/00002018-199513020-00004. PMID 7576268. S2CID 19809259.

- ↑ "Retroperitoneal Fibrosis Imaging: Overview, Radiography, Computed Tomography". 30 March 2017 – via eMedicine.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Silberstein, SD (1 Sep 1998). "Methysergide". Cephalalgia. 18 (7): 421–35. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.1998.1807421.x. PMID 9793694.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Archived copy". pdsp.unc.edu. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Rang, H. P. (2003). Pharmacology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-443-07145-4. Page 187

- ↑ Saxena PR, Lawang A (October 1985). "A comparison of cardiovascular and smooth muscle effects of 5-hydroxytryptamine and 5-carboxamidotryptamine, a selective agonist of 5-HT1 receptors". Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 277 (2): 235–52. PMID 2933009.

- ↑ Pubchem. "Methysergide". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- ↑ Colpaert FC, Niemegeers CJ, Janssen PA (October 1979). "In vivo evidence of partial agonist activity exerted by purported 5-hydroxytryptamine antagonists". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 58 (4): 505–9. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(79)90326-1. PMID 510385.

- 1 2 Knight AR, Misra A, Quirk K, Benwell K, Revell D, Kennett G, Bickerdike M (August 2004). "Pharmacological characterisation of the agonist radioligand binding site of 5-HT(2A), 5-HT(2B) and 5-HT(2C) receptors". Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 370 (2): 114–23. doi:10.1007/s00210-004-0951-4. PMID 15322733. S2CID 8938111.

- 1 2 3 Fitzgerald LW, Burn TC, Brown BS, Patterson JP, Corjay MH, Valentine PA, Sun JH, Link JR, Abbaszade I, Hollis JM, Largent BL, Hartig PR, Hollis GF, Meunier PC, Robichaud AJ, Robertson DW (January 2000). "Possible role of valvular serotonin 5-HT(2B) receptors in the cardiopathy associated with fenfluramine". Mol Pharmacol. 57 (1): 75–81. PMID 10617681.

- 1 2 Bredberg, U.; Eyjolfsdottir, G. S.; Paalzow, L.; Tfelt-Hansen, P.; Tfelt-Hansen, V. (1 January 1986). "Pharmacokinetics of methysergide and its metabolite methylergometrine in man". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 30 (1): 75–77. doi:10.1007/BF00614199. PMID 3709634. S2CID 9583732.

- ↑ Pubchem. "methysergide". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2017-09-06.

- 1 2 3 4 Majrashi, Mohammed; Ramesh, Sindhu; Deruiter, Jack; Mulabagal, Vanisree; Pondugula, Satyanarayana; Clark, Randall; Dhanasekaran, Muralikrishnan (2017). "Multipotent and Poly-therapeutic Fungal Alkaloids of Claviceps purpurea". Medicinal Plants and Fungi: Recent Advances in Research and Development. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants of the World. Vol. 4. pp. 229–252. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-5978-0_8. ISBN 978-981-10-5977-3. ISSN 2352-6831.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Paul Leff (10 April 1998). Receptor - Based Drug Design. CRC Press. pp. 181–182. ISBN 978-1-4200-0113-6.

- ↑ Ott J, Neely P (1980). "Entheogenic (hallucinogenic) effects of methylergonovine". J Psychedelic Drugs. 12 (2): 165–6. doi:10.1080/02791072.1980.10471568. PMID 7420432.

- ↑ Halberstadt, Adam L.; Nichols, David E. (2020). "Serotonin and serotonin receptors in hallucinogen action". Handbook of the Behavioral Neurobiology of Serotonin. Handbook of Behavioral Neuroscience. Vol. 31. pp. 843–863. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-64125-0.00043-8. ISBN 9780444641250. ISSN 1569-7339. S2CID 241134396.

- 1 2 Cavero I, Guillon JM (2014). "Safety Pharmacology assessment of drugs with biased 5-HT(2B) receptor agonism mediating cardiac valvulopathy". J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 69 (2): 150–61. doi:10.1016/j.vascn.2013.12.004. PMID 24361689.

- 1 2 3 4 Rothman RB, Baumann MH, Savage JE, Rauser L, McBride A, Hufeisen SJ, Roth BL (December 2000). "Evidence for possible involvement of 5-HT(2B) receptors in the cardiac valvulopathy associated with fenfluramine and other serotonergic medications". Circulation. 102 (23): 2836–41. doi:10.1161/01.cir.102.23.2836. PMID 11104741.

- ↑ Guzman, M., Armer, T., Borland, S., Fishman, R., & Leyden, M. (2020). Novel Receptor Activity Mapping of Methysergide and its Metabolite, Methylergometrine, Provides a Mechanistic Rationale for both the Clinically Observed Efficacy and Risk of Fibrosis in Patients with Migraine (2663). https://n.neurology.org/content/94/15_Supplement/2663.abstract https://www.xocpharma.com/file.cfm/7/docs/AHS_2019_Poster_1_XocPharma_Final.pdf

- 1 2 Dahlöf C, Maassen Van Den Brink A (April 2012). "Dihydroergotamine, ergotamine, methysergide and sumatriptan - basic science in relation to migraine treatment". Headache. 52 (4): 707–14. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02124.x. hdl:1765/73130. PMID 22444161. S2CID 29701226.

- ↑ Newman-Tancredi A, Conte C, Chaput C, Verrièle L, Audinot-Bouchez V, Lochon S, Lavielle G, Millan MJ (June 1997). "Agonist activity of antimigraine drugs at recombinant human 5-HT1A receptors: potential implications for prophylactic and acute therapy". Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 355 (6): 682–8. doi:10.1007/pl00005000. PMID 9205951. S2CID 24209214.

- ↑ Koehler, P. J.; Tfelt-Hansen, P. C. (November 2008). "History of methysergide in migraine". Cephalalgia: An International Journal of Headache. 28 (11): 1126–1135. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01648.x. ISSN 1468-2982. PMID 18644039. S2CID 22433355.

- ↑ "Sansert / methysergide maleate FDA New drug application 012516 international drug patent coverage, generic alternatives and suppliers". Deep knowledge on small-molecule drugs and the global patents covering them. Retrieved 2017-09-06.

- ↑ "CHMP referral assessment report" (PDF).

- ↑ 1966 Webb, John A. (30 Apr 1966). "Methysergide and Retroperitoneal Fibrosis". British Medical Journal. 1 (5495): 1100. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5495.1110-a. PMC 1844020. PMID 20790951.

- ↑ Graham, Jr (17 Feb 1966). "Fibrotic disorders associated with methysergide therapy for headache". N Engl J Med. 274 (7): 359–68. doi:10.1056/NEJM196602172740701. PMID 5903120.

External links

- Novartis Sansert site.

- Novartis Sansert product description.

- Migraines.org More detailed information on methysergide.

- neurologychannel.com, general information on migraines.

- History of methysergide in migraine.